W-E-B-S-I-T-E, Find Out What It Means To Me

Integration photo by Flickr user certified su (CC BY 2.0)

It’s interesting how many people don’t really understand the concept of open source. People often describe freeware as open source, or they’ll describe free web-based applications as open source, or applications with APIs that allow for mashups. There are articles all the time, on some of the most popular websites, that recommend free software but don’t distinguish programs the authors gives away for free from software that is actually open source.

For a program to be open source, it has to meet two basic qualifications

- The author has to provide full access to its source code

- The software has to be accompanied by a license that protects the contributions and rights of the community.

Perhaps what people associate most closely with open source—free software—is its price tag. However, it is often pointed out that open source software is usually free like a puppy or a kitten: there may be no cost associated with acquiring it, but there’s more involved than just the initial cost. As with software you pay for, it takes time and money to integrate new software into an existing computing environment. The difference between open source projects and software purchased from commercial vendors is that vendors profit from the time users spend on integration and workarounds (the stories they share on mailing lists and at user conferences add value to the commercial product) while fixes contributed to an open source project are owned by anyone who wants to make use of the software and are protected by its open source license. That’s why open source means more than just the zero on its price tag: the most essential element of open source is that the data is yours. Not just the data you entrust to the software, but the software itself. You are not reliant on the programmer who created it or the company that controls its license: you can alter it yourself or hire someone else to alter it for you.

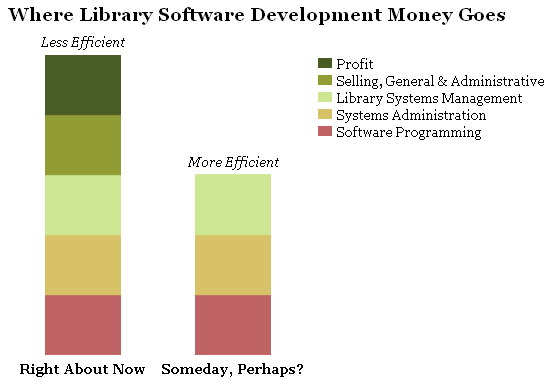

Of course, the initial price matters. When libraries buy proprietary software, they aren’t just paying programmers to write code, system administrators to make sure computing infrastructure is working properly, and managers to provide the programmers and system administrators with meetings and timelines. They’re also paying for the company’s overhead expenses (such as the salaries of the salespeople who sell them the software) as well as the company’s profit margin.

What if libraries hired every single programmer, systems administrator, and systems manager away from library software vendors—let’s say at exactly the same salaries they’re making now—and also purchased all their code and relicensed it as open source? The pool of employees making library software wouldn’t be any bigger, but the overall expenses for creating library software (less the one-time cost of purchasing the code) would be the same. Except it wouldn’t, because libraries would no longer be paying for sales and other expenses or footing the bill for vendors’ profit margins.

I’m not suggesting this is going to happen. Libraries aren’t organized enough to scoop up every techie at every library technology company, and even if they were, the companies aren’t going to sell their intellectual property.

No, I’m not suggesting it’s going to happen; I’m suggesting that it is happening. I’m suggesting that, within a few years, libraries’ software expenditure distributions will have changed. Rather than paying outside companies to employ library programmers, software developers will work directly for libraries. The code will be different, it will be better, and it will be open source. And, if library software is like other software, there’s a good chance that a lot of the code will be contributed by volunteers—people who aren’t even employed by libraries, but are interested in the problems and possibilities presented by creating software for library users and employees.

This is what happened with web server software, the programs that deliver code to web browsers (such as Firefox): open source software, especially the software released by the Apache Foundation, dominates the web server market. It also appears to be happening with web browsers themselves (Firefox again, though Google’s open source Chrome is off to a good start) and with the operating systems, primarily Linux, that run the computers on which web server software runs.

Once open source software is good enough, and has a good enough support system, there aren’t any particularly compelling reasons to use propriety software. Eventually, people come around to that realization, whether they care about the underlying code or not. The issues are that “good enough” is in the eye of the beholder and “eventually” can take an awfully long time.

A Quick Survey: Naming Names

When I took on the task of creating a new website for the Collingswood Public Library, I looked at the software options that were available to me. I was familiar with some of them from my jobs at other libraries, and it’s not hard to figure out what software libraries are running or to investigate what they’re doing with it: it’s mostly just a question of visiting their website. In my opinion, the leading open source options seemed good enough—perhaps no better than the proprietary software that dominates the market, but also no worse and, more importantly, the open source software seemed to be improving more quickly.

In my opinion, there are seven open source software projects worth considering

- Blacklight (demo)

- Evergreen (demo)

- Kochief (demo)

- Koha (demo)

- Scriblio (demo)

- SOPAC (demo)

- VuFind (demo)

There’s some apples-and-oranges going on here, in that some of these packages are just components of a website and require other software in order to do everything a library website needs to do (such as inventory management). Other packages cover the entire process.

Evergreen and Koha cover the entire process. Some people call them Integrated Library Systems, though I wish they wouldn’t.

Blacklight, Kochief, and VuFind provide usability improvements for people stuck with existing library websites. Some people call them Discovery Layer Interfaces and a few people would probably still refer to them as Online Publicly Accessible Catalogs. If you know any of these people personally, please ask them to cut it out.

SOPAC is still known to some as a Content Management System, and Scriblio is still occasionally referred to as a Blogging Engine, though they’re also sometimes lumped in with Blacklight, Kochief, and VuFind because, like these three, most libraries would probably choose to use them in conjunction with a system that assists with tasks like cataloging and circulation.

For us, and for most libraries that use library-specific software to handle their inventory, these were all viable options. The library where I work uses Innovative Interfaces’ Millennium, so these packages already work with it, could be adapted to work with it, or could replace it entirely.

Built from Scratch, on a Framework, or on an Application

One of the many advantages of open source software is that it’s often accretive: once one group of developers figures something out, they tend to share it. Other developers are then free to build software on top of it, and these developers generally share their improvements. Netscape opened the code from its browser and developers turned it into Mozilla. Other developers turned Mozilla into Firefox, which has been used as, among other things, the basis for a music player (Songbird) and scriptwriting software (Celtx). This kind of thing happens all the time.

For some uses, it’s nice to work with software that’s built from scratch. Other times, it’s nice to work with software that’s built on top of a framework—code designed specifically so that other code can be built on top of it. And sometimes it makes sense to work with software that takes software applications and adapts them to specific needs.

Both Evergreen and Koha were built from scratch, which makes sense: when they were started, there really weren’t any frameworks for them to use. VuFind is built on the Apache Foundation’s Solr project (which helps it optimize search), but its interface was built from scratch. Again, when VuFind was started, there weren’t any frameworks that made sense for it to use. If it were started today, it probably would use a framework, though that’s just speculation.

VuFind is partnering with Blacklight in standardizing Solr for library search. Blacklight also makes use of a framework, perhaps the best known among web developers: Ruby on Rails. Like VuFind and Blacklight, Kochief uses of Solr, but its interface is built using Django, a competitor to the Rails framework.

There are two projects that make use of existing applications: SOPAC is built on Drupal and Scriblio is built on WordPress. Both Drupal and WordPress are well known and widely used. To pick just library examples, ALAConnect and LISNews use Drupal; Jessamyn West, Jenny Levine, Karen Schneider, and Meredith Farkas use WordPress (and so do many—perhaps most—other successful library bloggers who run their own software).

In general, like most users I’m fairly agnostic when comparing software that’s built from scratch to software that’s built on a framework or an application, but this information was useful to me in this instance because I really know and like WordPress, the software behind several projects I’ve developed or helped to develop, including In the Library with the Lead Pipe. As with Drupal, Ruby on Rails, and Django, WordPress has a large and sophisticated user community. By choosing these applications and frameworks, the developers for Blacklight, Kochief, SOPAC, and Scriblio are making it easier for technically inclined people to understand what they’re doing and also making use of a large group of programmers and users who are helping them to develop their library website software, even though they probably have no idea they’re doing it. By improving the underlying software, they’re improving all the programs built on top of the framework or application.

Language

Although I may be the world’s worst programmer, I still consider the programming language used in building the software for one of my websites. Preferences tend to be idiosyncratic, and mine are no exception, but I try to be as objective as I can. For instance, I limit my choices to the languages that are popular (according to surveys like the TIOBE Top 20 or Programming Language Popularity) and that are typically used to build websites: Java, Perl, PHP, Python, and Ruby (all of which are open source). Languages (and frameworks) tend to be popular, and to add more developers, because they’re fun to use in developing software. Also, when a language is popular and fun to use, there tends to be larger group of programmers who will help you, or who you can hire, if you run into trouble.

Combining my language preferences with the previous consideration (built from scratch, on a framework, or on top of an application), here’s my ordered list

- PHP/WordPress

- PHP/Drupal

- Python/Django

- Ruby/Rails

- Python (from scratch)

- Ruby (from scratch)

- PHP (from scratch)

- Perl (from scratch)

- Java (from scratch)

This doesn’t disqualify any of the contenders. Here’s how they fit into my list

- PHP/WordPress: Scriblio

- PHP/Drupal: SOPAC (and also some of the eXtensible Catalog project, though this project is not yet available for use or testing)

- Python/Django: Kochief

- Ruby/Rails: Blacklight

- Python (from scratch): N/A

- Ruby (from scratch): N/A

- PHP (from scratch): VuFind

- Perl (from scratch): Evergreen (though it’s being extended in other languages) and Koha

- Java (from scratch): N/A, though the eXtensible Catalog already makes use of Java, and OLE, which is still in the planning stages, may make use of Java as well, though I’m mostly just speculating on this point. My disinterest in Java, which I’ll admit is mostly just second hand, also helps to explain why I like Moodle (PHP) for educational websites better than its open source competitor, Sakai, which is built on Java.

Documentation

One of the advantages that commercial, proprietary software often enjoys over its open source competitors is documentation. This makes sense from a commercial perspective: write the documentation, point customers to it, and you can save on customer service. The catch is that documentation for commercial software is often hidden from search engines, so finding an answer to a question about commercial software often means navigating the vendor’s documentation or sending a message to its mailing list. At a previous employer, we were contractually obligated to constrain employee access to Innovative Interfaces’ documentation. While Innovative’s information was well written, the search engine that was built into it was awful, so finding answers was often frustrating. The plan, when I left, was to buy a specialized server we could use to run our searches through an access-restricted Google search.

Open source developers often seem more interested in improving the software than in writing documentation. It’s also a separate skill from writing code; people who are good at programming, and enjoy it, are not always the same people who are good at, and enjoy, writing documentation. As projects grow, people interested in writing documentation tend to get involved—and they make their discussions public. Users and developers post their thoughts about issues they encounter and they link directly to the documentation, which means search engines become one of the best resources in understanding a feature or solving a problem with open source software.

The programming languages I’ve cited all have excellent documentation, as do the frameworks and the applications. Among the full-service website software, Koha, the older of the two, has fuller and more user-friendly documentation, at least in my opinion; Evergreen’s is good and improving, but doesn’t yet appear to be as polished or accessible as Koha’s.

Among the other projects, VuFind and Blacklight probably have the best documentation—certainly enough to get you started, and SOPAC, though the newest of the bunch, has done a very good job with the basics, though as of this writing it is open about the absence of documentation for its more advanced features.

I’m probably hardest on Scriblio because it’s the project I know best, but Scriblio’s documentation lags behind its peers and even relatively basic questions often need to be answered on the mailing list. To Scriblio’s credit, these questions do get answered, but its lack of documentation is probably Scriblio’s most notable shortfall (for instance, as of this writing its internal record format, Marcish, is not yet documented on its website). Among the list of major open source library website software projects, Scriblio is ahead of only Kochief, which is in the earliest stages of the documentation process.

Stability: Leadership, Community, Funding

When commercial software vendors go out of business, they often take their software with them (unless they sell it to another company or, like Netscape, decide to release it as open source). That’s not a danger with open source software: as long as someone has a copy of the code, it remains available. I’m not aware of any significant open source projects that have simply disappeared. However, plenty of open source projects seem to die off when their developers stop making time for them. While it’s possible to revive stagnant projects or take them in another direction (WordPress, for instance, was a reinvigoration of b2/cafelog), it’s still advisable to look for projects that have a strong, stable community—especially for something as important as the software that powers your website.

As with documentation, stability is not really an issue for any of the languages, frameworks, or applications I’ve mentioned. However, it seems like it may be more of an issue for the library-specific projects.

Koha and Evergreen are closely associated with private companies that offer consulting for these projects. Josh Ferraro, one of Koha’s early adopters in the United States and the release manager for Koha 3.0, created LibLime in 2005 in order to focus on providing support for Koha users in North America (Koha was released in 2000 and has a longstanding, active community in New Zealand and Europe; reading its well documented history and learning about its unsung heroes are good ways way to learn how open source projects evolve). While Koha is as strong as its developer community—currently at about 90 developers, which is quite good—it seems likely that LibLime’s success and Koha’s will be intertwined for some time.

Unfortunately, there may be reasons to be concerned about LibLime. Most of what I’ve heard is just rumor, though in the last few days the LibLime website’s management team page ceased to display photographs and blurbs about two of its members, Debra Denault (Senior Vice President, Operations) and Galen Charlton (Vice President, Research and Development, and the manager for the newest Koha release, version 3.2). LibLime also pulled its promised funding from the code4lib conference earlier this year rather suddenly and unexpectedly, or so it seemed to me. There could have been a non-financial reason for this decision, or it could have been a conservative move (the conference took place right after the sudden 2008-2009 downturn).

Just to be clear: I’m doing my best not to pass on gossip as fact, especially about a company whose employees I’ve met, respect, and like very much—and who funded a presenter, Aaron Swartz, when I found out last minute that ALA wouldn’t waive Aaron’s registration fee for the Midwinter in Philadelphia (even though he was addressing our discussion group for free and paying for his own travel expenses). And I’m not suggesting that either LibLime or Koha is in trouble. LibLime is an important contributor to Koha, but even among “pay for support” organizations, Koha is bigger than LibLime. Still, just as it’s worth understanding what’s going on with automobile manufacturers before you buy a new car, it’s worth getting to know a bit about the groups who are working on your website software, whether they’re private companies or open source communities.

Evergreen, which was initially released by a consortium of Georgia libraries as the PINES catalog, saw several of its initial developers go on to found Equinox Software, a company that consults on Evergreen installations. Equinox has hired extraordinarily talented people, they’re hiring (which is always a good sign), and they have talented volunteers contributing code back to the project. To bring this back to the model I sketched out in the introduction, most of these “volunteers” are employed by libraries, not by Equinox/Evergreen.

The rest of the projects have what could be considered a single point of failure: if their lead developer or sponsoring department were to abandon the project, they would likely lose a great deal of momentum. I believe, in each case, they would eventually regain that momentum or I would not have included them in this survey, but it seems clear to me that the other five projects are potentially less stable than Evergreen or Koha.

Based on its code updates, VuFind appears to be adjusting well to its transition from being someone’s primary responsibility to being a community-based project. Andrew Nagy founded VuFind while working for the library at Villanova University (VuFind is a pun on VU). He has since moved on to Serials Solutions, where he is one of the leaders of its Summon product. VuFind has received a Mellon Award and professional support is available through Lyrasis, both of which are encouraging. However, it would be nice to see a new release (VuFind’s latest release is its first release candidate for version 1.0, which came out on October 15, 2008) and, Lyrasis, though large and diversified, is undergoing its own changes, so VuFind could find itself with no organization other than its original developers offering commercial support.

Blacklight and Kochief are similar to VuFind, or at least to where it was when it was mostly a Villanova project: Blacklight is being supported primarily by the University of Virginia library and Kochief primarily by the Drexel University library. Both look great and are under active development, but neither has a large base of installed users. This is significantly mitigated by their use of popular languages and frameworks, but lack of support by Virginia or Drexel (at this point mostly Drexel’s Library Systems Developer, Gabriel Farrell) would be major blows to these projects.

As far as institutional support, Scriblio and SOPAC are a study in contrasts. Scriblio isn’t technically based at a library: Casey Bisson, its lead developer, works as an Information Architect at Plymouth State University, but he works centrally, not just for the library. He has, however, secured funding for Scriblio from the Mellon Foundation and also joint funding from the NEH/IMLS. Meanwhile, SOPAC’s development has been funded by two of the finest and best funded public libraries in the country, Ann Arbor and Darien, lead developer John Blyberg’s former and current employers. Neither Scriblio nor SOPAC yet have large developer communities or installed user bases, and both remain highly reliant on their lead developers.

Self-Hosted or Outsourced

One of the advantages of open source website software is the empowering feeling of downloading the software and running it on servers you control. However, it’s also useful to have the option of paying someone knowledgeable to run the software on their servers: as mentioned above, system administration is a career and an expense unto itself. Some software offers the best of both worlds: go to WordPress.org and you can download WordPress and install it on your own servers; go to WordPress.com and you can sign up for a free website that’s powered by WordPress software, but works much like Blogger or any other hosted software. In exchange, you give up a certain amount of control, but for many people it’s a welcome tradeoff.

LibLime and Equinox specialize in their projects and offer hosting for them at what I consider reasonable prices. Scriblio has a free hosting option that it is slowly rolling out to smaller libraries—an equivalent service to the WordPress.org/WordPress.com website option. For us, that was a big attraction. We give up some control, but taking server administration tasks and expenses out of the equation is a huge net win.

To the best of my knowledge, there are no dedicated VuFind, Blacklight, Kochief, or SOPAC hosts, though there are companies that specialize in PHP, Rails, Django, and Drupal. For instance, Palos Verdes Library District, which just released its SOPAC-based website, hired CraftySpace to guide its implementation. Help is available for running and hosting any of these projects, but for now managed hosting is most closely tied to Koha, Evergreen, and Scriblio.

Choosing Scriblio

For me, the initial decision to use Scriblio and the ongoing decision to stick with it are both difficult and obvious. I really like using WordPress and know it well—I created a very basic Scriblio site even before I had my first interview for my current job, and setting it up took just a few hours—and I really like Casey Bisson as a person and as a web developer: our visions for libraries are awfully similar. For instance, Scriblio creates unified websites: for Scriblio libraries, the catalog and the rest of the website look alike and run on exactly the same software. What closed the deal for us was Scriblio’s ability to pull in funding and its decision to turn some of that funding into free hosting for CollingswoodLib.org (and similar libraries).

Scriblio isn’t perfect, but I’m very comfortable with Scriblio and excited about where it’s heading. While I’ll be happier when there’s a larger developer community, more internal interest in standards, and better documentation, I have the ability to help make these changes. In particular, as one of Scriblio’s early adopters, I bear more than a little responsibility for not having done more to improve its documentation; remedying this situation is high on my to do list. However, perhaps the main problem I have with Scriblio is that my satisfaction with it diminishes my interest in getting more direct experience with the other software I could be using for our website.

If I were a more talented programmer, I’d probably choose Kochief because I’m most interested in learning Python and Django. I’ve also commented on my admiration for Gabriel Farrell elsewhere on this website. Blacklight would probably be my next choice if I knew what I was doing: plenty of programmers I admire are fans of Ruby and Rails. If I were more interested in PHP, or was interested in hiring a developer, I’d strongly consider VuFind. Its user interface is attractive and polished, and a lot of good thinking and good work has gone into this project.

If I had more money to spend on implementation and training, I’d hire LibLime to host Koha and migrate our data, or Equinox to migrate us over and host us on Evergreen. My hope, which I try to make real via advocacy, is that a larger entity than Collingswood—Camden County, VALE, the New Jersey State Library—will make this decision and include us as partners. From what I’ve seen, I strongly prefer Koha and Evergreen websites to what Millennium offers. As for choosing between the two, I’m not yet able to do it and don’t see any reason to decide just yet, though I have learned enough to decide that I don’t yet want us to abandon Millennium on our own. When the time comes to migrate our data, both projects will have changed, plus we’ll be making the move alongside partners. Fortunately, Koha and Evergreen are both great and getting better. I’ll decide later which one I most hope to use.

If I were to leave Scriblio tomorrow, the project I’d likely leave it for would be SOPAC. While I prefer WordPress to Drupal, it’s mostly because I’ve been working on smaller projects: Drupal was initially developed with more complex websites in mind, while WordPress was initially developed to handle simpler sites. They’ve been converging for years, as WordPress has gotten better at bigger sites and Drupal has gotten better at smaller sites, but there’s still a perception—one I admit to not having tested in a few years—that Drupal is better at handling larger websites. I also like the fact that SOPAC, like Scriblio, creates more unified websites (why is it that most libraries still subject their users to a website that includes the catalog only as an adjunct?) and that SOPAC has Darien Library as its primary funding source and John Blyberg as its lead developer. Plus, it’s attractive, flexible, and fairly easy to implement: all in all, a deserving winner of LITA’s 2009 Brett Butler Award.

For now, I’m happy with Scriblio. It meets our basic needs and is steadily improving. Perhaps the best endorsement I can offer for Scriblio, at least for smaller, public libraries like Collingswood, is my endorsement of its competitors. We use Scriblio in spite of its competition, not because of it.

Thanks to Casey Bisson, Nicole Engard, and Gabriel Farrell for reading an early draft of this article, and to my ItLwtLP colleague, Derik Badman, for helping me with its final version.

@Brett – I think Turo Technology LLP is now to software.coop what Metavore Inc is to LibLime, but I’m no longer allowed to update the Koha “pay for support” page.

@David – Koha uses/builds-on Pazpar2, YAZ and Zebra. IndexData are a pretty interesting company.

@Susan – the question wasn’t “do librarians care” but “do librarians care more“. In other worse, has the increase in collapse probability of debt-fuelled vendors moved community sustainability up librarian priority lists?

Pingback : HotStuff 2.0 » Blog Archive » Word of the Day: “brett”

As previously quoted by Kyle:

there’s a good chance that a lot of the code will be contributed by volunteers—people who aren’t even employed by libraries, but are interested in the problems and possibilities presented by creating software for library users and employees.

The work that volunteers do for our libraries can and should never be underestimated. With the current economic climate, libraries are cutting programs and staff. Hiring new programmers to write code may be unlikely. Therefore, finding knowledgeable and willing volunteers could be our saving grace.

Enjoyed reading this. Two comments/questions. You mentioned that you wish people would stop referring to Evergreen and Koha as integrated library systems. I am curious what term you prefer. I am not fond of this name, either, but it is at least widely understood, for better or worse.

The other aside concerns the distribution of Koha. You mentioned that it has an active community in Europe. A student of mine (Germany) just wrote a thesis about Koha and noted how rarely it is used in Germany, and that it is generally not widely used in Europe. A glance at the Koha showcase (http://koha.org/showcase) shows this, although I am aware of how graphical representations like that can be skewed base on who chooses to enter themselves there. It is hard, in general, to say what Europe is these days. Countries such as Germany and, say, Hungary, are about as dissimilar as can be in many ways.

Thanks, Dale, for reading this piece and for the compliment and comments.

As I wrote in response to a previous comment, “My primary issue with the jargon is that it seems to be institutionalizing decisions that no longer make sense. Amazon has a website. We have an alphabet soup of software that’s getting better, but still doesn’t come close to competing with the user experience Amazon offers.”

Here’s what I was trying to get across: programmers should call the components of library website software whatever makes sense to them, but people who are buying the software (or making the decision to use open source software, whether they buy support for it or not) should focus on their website, not its components.

I think the reason we don’t focus on how people use our websites is because of our history. Some of the terminology predates widespread adoption of the graphical web and we’ve been slow to change it because, as you point out, it’s widely understood. But I think that’s the secondary reason.

I think the primary reason we’re all expected to learn arbitrary terminology is because vendors want us to buy each piece individually: the more pieces we buy, the more we have to negotiate, and each negotiation favors the vendors (they negotiate sales all the time, and as often as possible; we negotiate purchases as infrequently as possible). I’ve already been scolded by one vendor for revealing in an earlier Lead Pipe article how hard they made it for me to get an answer to a simple question: “What’s the least it will cost us to share the Collingswood Public Library’s catalog on your website?”

The answer to the Europe question is simpler: I asked someone who’s actively involved with the Koha community and that’s what was reported to me. In addition, I noticed that France’s BibLibre is the only company, aside from LibLime, that is listed as “a Major Community Contributor.” Note: I’m not diminishing other community contributors–I don’t follow Koha closely enough to have formed my own opinion–I’m just quoting what I read on the Koha Pay for Support page.

Note that koha.org (and so the showcase) is now controlled by LibLime, so is inevitably skewed. The KohaUsers wiki page is more open, but even then, European procurement models are less sympathetic to Koha, so those who buy Koha may not be so willing to publicise it loudly.

Koha installer software.coop has recently changed its standard terms of supply to allow us to add users to listings unless they say otherwise.