Why isn’t a picture worth a thousand words?

In the Library with the Lead Pipe is pleased to welcome another guest

author, Kristine Alpi! Kris is the Director of the William Rand Kenan, Jr. Library of Veterinary Medicine at North Carolina State University Libraries.

Why do document delivery technologies limit information transfer?

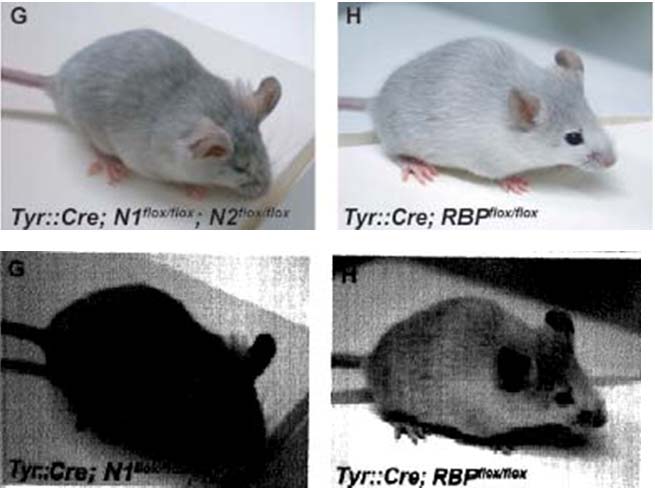

Modified from the original — permission for the use of this derivative work has been requested from the publisher of Histology and Histopathology.

The technologies that libraries use for interlibrary loan and document delivery frequently reduce the value of the information available to be delivered. In the past, color was used sparingly by publishers concerned with printing costs, and readers could assume that most images were not available in color unless dealing with visual arts publications. Although entire books have been written about the value of color as communication, color has always been a special request for interlibrary loan copies. Now, color is much more common: in situations where color is crucial and in cases, such as graphs, where well-presented shades of gray could convey the message. In 2001, the Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry began offering one full page of color figures per article at no cost to authors since the majority of their content required color images [1]. Scholarly disciplines that need color to convey meaning are not having their needs met by interlibrary loan/document delivery (ILL/DD). Growth in the frequency and quality of image reproduction in pathology, molecular biology, microsurgery, and other highly visual aspects of science has changed the amount of content for which color is absolutely essential to shared understanding. The 275,000+ papers on the subject of gene expression covered by PubMed provide just one example.

Standards?

Neither color nor image quality is mentioned in the American Library Association Interlibrary Loan Code for the United States (Revised 2008, http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/rusa/resources/guidelines/interlibrary.cfm) nor the sample ALA Interlibrary Loan Request Forms. Most standard library forms and processes assume that a readable black and white scan (B&W) is sufficient to meet user needs. Library staff in academic, public and special libraries, large and small, have suggested to me that the images don’t matter because users just skip over the pictures or data in favor of the text; that doesn’t fit with the browsing patterns of many users who go straight for the data tables or images. I would argue that the reason readers might undervalue images in their interlibrary loan articles is because the image quality has typically not been able to convey the message from the original publication. Warner (2004) compared the quality of print original journals, custom supply photocopies from the Canada Institute for Scientific and Technical Information (CISTI), and the online and printed quality of Ariel transmitted files and found the Arieled copies lacking [2]. Ariel has gone through several upgrades since his 2003 exercise, but it is not clear how many libraries have upgraded their Ariel software or how the upgrades of the Ariel technology centered around TIFF file transmission have attempted to take advantage of global improvements in non-library imaging devices and software. The corporate website (http://corporate.infotrieve.com/ariel) positively comparing its transmission to fax quality suggests a need to aim higher.

Why aren’t we pushing the envelope to provide a more accurate and usable facsimile of the original article?

If pushing our ILL/DD partners to scan in color or grayscale isn’t feasible, purchasing the original article is a viable option from some publishers. Image and data technologies have made tremendous advances, but if you ask document delivery staff why color is not more widely supplied, the answer will almost always come back to the technology as a limitation. File size challenges, difficulty with email attachments and file transfer software, old versions of scanning software, or the scanners themselves are cited as the barriers. Lack of color printing in the borrowing library was often a concern back when all articles were printed and mailed or faxed. Now, the borrowing library does not need to offer color printing of the final document received in order for the acquisition of a document in color to be useful. If the item is to be delivered electronically, the user can view it in color or may have affordable access to color printing at home or elsewhere. Also, a black and white printout of a color scan will have more contrast and distinction than printing a B&W scanned document.

Even when the color technologies are available, our ILL/DD requesting systems do not facilitate color requests. The requesting library staff may not have time to consider whether the material carries content in color based on the citation, but requesters probably have some idea after reading the abstract. Users could use the Notes field to make this request, as many have, but asking the question about color up front could save the time of the user and library staff and allow the color request to be made in an automated fashion. It would be better to ask for and use this information on the initial request, than to acquire a B&W copy and then hear from the requester that what was received is unsatisfactory. One of our anatomic pathology trainees is learning the hard way to request color or grayscale after having to wait on replacement color copies for several poor quality B/W documents received via Ariel.

Automating the ordering of color increases its usage.

The National Library of Medicine’s DOCLINE interlibrary loan request system added color copy requesting in December 2003 due to user demands for biomedical literature which features images that need to be seen in color for the reader to fully understand the message. The number of color requests has grown as a percentage of the overall DOCLINE requests from .02% of the overall requests in FY2004 to .14% of the 1.5+ million total requests in FY2009. While 2,217 color requests may seem paltry, this data reflects only requests for which library staff indicate a color request using the system select box, not those that use the Comments field. Because so few lending libraries indicate that they provide color copies, some borrowers will not select the color request checkbox, but will add a comment to the lender indicating they prefer color if available and at no extra charge. In these cases, getting the article content is more important than getting that article in color.

DOCLINE is primarily a tool of biomedical libraries. What about academic basic scientists and clinicians using public libraries who rely on OCLC Resource Sharing? Do these users realize that color is a choice either when ordering direct via WorldCat or using library forms? How are we limiting the range of possibilities and why? Is it accidental or intentional? Right now, a borrowing library asking for a color copy in OCLC must entertain several possible steps of additional effort—you can pre-identify lenders that provide color and route requests to them or you can make it a note for the lending library staff to receive and respond—where the resulting conditionals can add time to the request. Some libraries warn users that color copies can take longer:

Color copies are available through MINITEX for articles with color charts and graphs. If you need a color copy please make a note of that in the “Comment” field when sending your request. Color copy can take up to two days longer to obtain. http://www.morris.umn.edu/library/ill.php

Asking for color shouldn’t have to slow down the process, but it does when the request forms and shared systems don’t match the right user need with sufficiently detailed information about the lending libraries. Warning users creates more realistic expectations, but it can also dissuade users from requesting color if they need the article in a timely fashion. In a system like DOCLINE where color capacity and requesting is automated, the turnaround times for color are frequently the same as B/W. Users may also be hesitant if they aren’t sure whether an article is actually in color, especially if there are color-associated charges. If not able to fill in color, should the lending library share the information about the pages in color with the requesting library as a conditional response so that the library or user can make a fully informed request?

What about Document Delivery?

How do libraries providing document delivery handle images for their own clients? CISTI offers custom supply service to meet the needs of researchers who require high-quality color or grayscale images. In Warner’s report, these documents were supplied as high-quality photocopies—there is no information about this service on the CISTI website that I can find. The British Library Articles Direct request form does not ask about color—the requester will need to complete either the “Additional details” or “Specify special requirements.” A naive user might assume that color articles come in color and that articles with images will be scanned with the best available photo imaging technology and never realize whether the original article was in color or not. The Linda Hall Library addresses this issue in their Email Delivery Frequently Asked Questions:

Although the typical file size delivered will be less than 2MB, grayscale and color images will create files of a far greater size. Linda Hall Library will not scan in color for electronic delivery unless specifically requested to do so. Please do not request color scanning for electronic delivery unless your email is able to accept files of at least 10MB.

Asking for color isn’t all rosy.

The fill rate for color requests is lower. Per the institution records in DOCLINE, only 243 libraries report providing color copies with 32 of those libraries charging extra for those color copies. For example, the National Library of Medicine charges $2.00 more per item in color and the Linda Hall Library charges an additional $1.00 per page for color copies. What would our users say about the value of color or grayscale images if we asked—would they pay differential rates? Why should they? Why do libraries charge more for color when it is now mostly scanning? It could be that they only have one color price option in the software and still need to deliver paper copies. It is true that a paper copy in color costs more in toner—though that difference in cost is decreasing. But what is it in the case of scanning—is it a matter of staff time spent since it takes a few seconds longer with many scanners to acquire a page of images in color or grayscale? It may also reflect trying to spread out the cost of more expensive color scanning equipment. While low volume flatbed scanners are inexpensive and offer B&W, color, and grayscale, there are significant price differences between color and B&W versions of the large overhead scanners used for tightly bound and duplex page scanning. Are libraries who pay for ILL/DD trying to avoid the extra cost for color? More likely it is just that they haven’t revisited these options as their technology and workload has changed.

Providing color can create the blues as well.

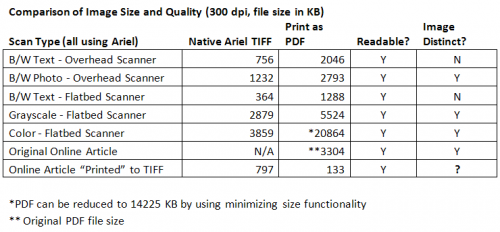

At the William Rand Kenan, Jr. Library of Veterinary Medicine, we want to provide the most informative materials possible. We often scan color plates in color or detailed images in grayscale, but we run into all kinds of problems in delivering these large files to other libraries and directly to our users. Our processing choices result in very different file sizes and image quality, though the readability of the text remains about the same. Below is a table showing the five possibilities available in the Veterinary Medicine Library’s operation. Our example was a selection of three pages (613-5) from the paper “The Notch pathway: hair graying and pigment cell homeostasis” in the journal Histology and Histopathology [3]. We accessed the article online in the original PDF, as well as scanning the print file in all the available options using Ariel 4.1.1.99 with our two scanners—a black and white Minolta PS 7000 overhead scanner and a color HP ScanJet 8290. We also looked at printing an online article to a TIFF file using the Microsoft Document Image Writer which turns the color images to grayscale and pixelates the images, a loss of image data quality. The image quality is still much better than all of the B&W scans, and this is our only option to securely deliver online-only content without printing and rescanning. The opening image in this article shows a side-by-side comparison of an original image in the online PDF article with the output from B&W text scanning.

The results of our scanning experiment with 3 pages of an article with many images.

The size limit for an email attachment at North Carolina State University is 15 MB including the encoding, which increases the file size by about 30%. This is a fairly typical limit with many organizations being restricted to even smaller attachments. It is clear from the email delivery addresses used by many Interlibrary Loan departments in DOCLINE that they have created free email accounts on external services in order to send and receive materials. The file attachment size limits of 25 megabytes per message for gmail.com and yahoo.com are more generous than university or hospital IT policies. Other strategies that have been espoused on discussion lists are using the free levels of services such as YouSendIt™ (http://www.yousendit.com/). In order to deliver to non-Ariel libraries and individuals with these email limitations, we have posted their scanned documents online and emailed them the URL for download. In some cases however, people still have trouble opening, viewing, downloading, and printing the files from their computers, and it is very difficult to help troubleshoot these issues remotely during the very busy workflow of the interlibrary services function. Other ILL departments have reported that they cannot receive and therefore disseminate color documents electronically via their version of Ariel software because it is attached to a B&W scanner which is not something the lending library can tell from the sending end. Odyssey software has been reported to work with black and white, grayscale, color, or any combination of these scanned formats, albeit slowly. Perhaps its widespread dissemination will address some of these file size transmission issues as more libraries have delivery software. It is clear from the ILL/DD community discussion list questions that a great deal more improvements to speed and functionality are needed in all of these products.

Breaking the Color Barrier

Library procedures and technology really shouldn’t be a barrier to sharing color information. All partners in the borrowing and lending chain have a role in providing the highest quality information. Ideally color scanning of color images at no additional charge would be the default practice. Absent that sea change, borrowing libraries should get users thinking about whether color is needed and explicitly ask them on request forms whether color is preferred. Lending libraries should indicate whether they provide color or grayscale scanning or copying services and any associated charges. Lenders can also look out for materials where the typical scan doesn’t provide sufficient information and use the options in the technology at their disposal to optimize the images. Resource sharing systems should provide an automated way to match the user’s request for color materials with lending libraries’ capacities for filling requests in color. Resource sharing software should provide options to deliver better compressed versions of files that reduce the file size burdens for file transfer. Institutional information technology departments should be more flexible in allowing large file size attachments or providing easy-to-use, secure file transfer services. Lastly, funding agencies can work with libraries to help them obtain faster and more effective scanning technologies and software as prices and functionality improve.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Maria Collins, National Library of Medicine, for providing data about color requesting in DOCLINE and to Beth Westcott of the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, Southeastern/Atlantic Region for discussing this article proposal with me. Discussions with James Harper, Librarian for Interlibrary and Document Delivery Services at North Carolina State University, greatly affected this piece and broadened my point of view. Thanks to Lead Pipe reviewer Derik Badman for his comments and edits and to Kimberly Burke Sweetman at New York University for her review and thoughtful questions. Lastly, the ILL/DD staff at NCSU deserve recognition for the care they give to the images in each item they provide.

References

1. Baskin DG. Free color pages. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2001; 49:551-2.

2. Warner P. CISTI Source and journal use at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Interlending and Document Supply. 2004;32(4):215-8.

3. Schouwey K, Beermann F. The Notch pathway: hair graying and pigment cell homeostasis. Histology and Histopathology. 2008;23(5):609-19.

I’m so glad to see an article about this. I work at an academic research institution and have several faculty that lament about the poor quality of ILL scanned copies. Article delivery services are seriously behind the times and the service risks becoming irrelevant if we can’t provide high quality documents.

Thanks for the encouragement. I think we’ve worked really hard to improve ILL/DD speed and now quality is the next frontier!

Color images are also useful for the visual arts…Art & Art History, Studio Arts, Museums…

As someone with a History of Art degree, I completely agree with you about the utility of color. Art researchers that I have known tend to address their need for color when making requests. I assume that art libraries have high-quality color scanning technologies available for their users, but I am not sure whether that carries over into their ILL/DD services.

Do you have any best-practices you can share in regard to what scanner settings to use when providing color copies? Do you recommend decreasing the DPI when using color to help limit file size? Do you know what the maximum file size is for sending via Ariel or Odyssey and approximately how many color pages it takes before that maximum is reached? Some practical advice based on your experiences would be great!

The ILL/DD community is definitely home to the practical advice for dealing with the systems we have today. I hope this will launch a discussion about color that leads to best practices for today and the future.

I don’t have an answer for your specific questions, but hopefully the Ariel and Odyssey developers are reading and can respond. Experimenting with your scanning technology and version of the software, as well as incorporating other file reduction strategies can help you reach a happy medium on what is useful to users but distributable to the average library. We have seen that trying to reduce DPI to make color files smaller can make the text hard to read–be sure to take care for the text as well as the images. Good luck!

One issue is that some publishers we love to hate won’t let a library with an electronic subscription loan an article unless they print it out and then rescan it. Degraded quality guaranteed, but more by order of the publisher than by the library. This is likely to be a growing point of friction as more and more journals are online only (but still incredibly expensive).

Open access week, here we come!

Publishers are certainly part of this equation. While many libraries have color scanning capacity, many do not have the ability to print in color and then re-scan. And as you say the time to do so and the quality are another barrier. This is where publishers need to offer reasonably priced and convenient direct article purchase models so that libraries will be able to purchase the original content for less than the transactional cost of an ILL request.

Even when requesting image-heavy art history articles, I still receive horrible black and white copies. I can see how color may be cost prohibitive, but decent grey scale images would work better than the illegible images in ILL articles.

I suspect that many of these older publications were digitized from microfilm copies. The microfilm has a pretty lousy tonal range, so the resultant image is virtually useless before it gets compressed even further by scanning and Ariel.

I’m a big fan of decent greyscale images, and in many cases those will do the trick at a more manageable filesize. Greyscale options are available in Ariel and Odyssey and I’d like to see them used more often as a default as well.

We’ve considered buying articles for individuals as opposed to ILL but libraries like ours are having to budget tens of thousands of dollars to fund such programs (which benefit people one on one, can’t be used by anyone else) – we don’t have that kind of money. It also is an abandonment of the idea of fair use. I have very mixed feelings about the pay per view library, but since I have no money for it anyway, I don’t yet have to confront them head-on.

The main reason I mention pay per use is that sometimes our users need the type of image quality and flexibility to manipulate that can only be provided by the original image. Depending on their intended use of the image that requires that sort of quality, it might be more appropriate that they purchase the item directly from the publisher. All publishers with online content should be encouraged to have a reasonably pricing per per view option.