Answering questions about library impact on student learning

Photo by Flickr user WordShore (CC BY-NC 2.0)

This essay reports on a project which evaluated the Understanding Library Impacts (ULI) protocol, a suite of instruments for detecting and communicating library impact on student learning. The project was a dissertation study conducted with undergraduates enrolled in upper-level and capstone history classes at six U.S. colleges and universities in 2011. My first essay for In the Library with The Lead Pipe introduced the protocol and provided background on the approach. This essay uses selected results from the 2011 project to demonstrate how the protocol works and suggests ways readers can get involved with future ULI projects.

High expectations for higher education

These are trying times in U.S. higher education. Only 63% of U.S. students who enroll in college graduate within six years[1] and the U.S. now ranks 12th among OECD nations in college participation rates among young adults.[2] Further, the Lumina Foundation predicts a shortfall of 23 million college graduates in the U.S. by the year 2025.[3] Students and parents are also questioning whether the benefits of a college degree justify the ever-increasing costs of attending college.[4] Stakeholders and customers are seeking reassurance that colleges and universities are delivering value for money. In these belt-tightening times, all units on campus, including the academic library, are under scrutiny.

Support for teaching and learning is at the heart of most academic library mission statements. Yet, never has it been more important for libraries to demonstrate evidence of this support. The Association of College and Research Libraries’ (ACRL) Value of Academic Libraries Report charges academic libraries to meet this challenge. One of its central recommendations is for “libraries to … define outcomes of institutional relevance and then measure the degree to which they attain them.”[5] The ACRL recognizes the importance of this issue in its recently revised Standards for Libraries in Higher Education. The new standards differ from previous versions by setting clear expectations for libraries to “define, develop, and measure outcomes that contribute to institutional effectiveness and apply findings for purposes of continuous improvement.”[6]

Just what outcomes do libraries influence? Where should libraries focus their assessment efforts? Retention and graduation rates are logical outcomes to consider, but student learning outcomes are the gold standard in higher education accountability. Demonstrating library impact on student learning has proven challenging work. Roswitha Poll and Phillip Payne (2006), for instance, point out several difficulties in measuring library impact on student learning including the possibility that services can have different effects on different user groups, difficulties in accessing student performance data, and the diversity of methods in use prevent benchmarking of any sort. [7]

In my opinion, doing nothing is not an option. Libraries need efficient methods for connecting student use of the library with the learning outcomes that matter most to faculty and stakeholders. Failure to do so leaves libraries out of important campus conversations about student learning.

The ULI protocol is designed to meet this challenge.

What are student learning outcomes?

For several years, academic libraries have communicated impact in terms of information literacy outcomes. As I wrote last year, information literacy outcomes are important but they are not the only learning outcomes stakeholders are interested in. The ULI protocol broadens the scope for library assessment beyond information literacy to the student learning outcomes associated with the academic major. Learning outcomes expected of graduates within an academic major describe the competencies most clearly defined by faculty and best understood by stakeholders. For instance, a recent graduate in the discipline of History would be expected to demonstrate the abilities to ‘frame a historical question,’ ‘build an argument based on evidence,’ and ‘communicate the argument coherently.’

The ULI protocol further focuses the library assessment lens on capstone projects in which undergraduates are expected to demonstrate these abilities. A capstone experience such as a research project or independent study is considered a high impact practice in undergraduate education. Students engaged in high impact practices work hard, interact with faculty and classmates in meaningful ways, and report higher learning gains than peers. [8] The capstone makes a good focus for assessment because these are times when students demonstrate the skills expected of graduates, faculty expectations are at their highest, and student effort should be at its peak.

Learning expectations in capstone courses can be described in a rubric. Rubrics are intended to serve as “scoring guides” to “help clarify how instructors evaluate tasks within a course.”[9] For example, the Utah State University History department created a capstone rubric which defines a set of expectations for grading student papers in the key areas of historical knowledge, historical thinking, and historical skills:

Table 1

Learning outcomes for capstone History papers

- Student demonstrates an understanding of the key historical events related to the thesis (outcome 1)

- Student frames historical questions in a thoughtful, critical manner (outcome 2)

- Student evaluates and analyzes primary sources (outcome 3)

- Student evaluates and analyzes secondary sources, demonstrating an awareness of interpretive differences (outcome 4)

- Student employs a range of primary sources appropriate to the informing thesis (outcome 5)

- Student employs a range of secondary sources appropriate to the informing thesis (outcome 6)

- Student presents a well-organized argument (outcome 7)

- Argument is well-substantiated; student properly cites evidence (outcome 8)

- Student employs proper writing mechanics, grammar, and spelling (outcome 9)

Adapted from the capstone rubric used by the Utah State History Department [10]

If professors and instructors are assessing student work for these outcomes, library assessment tools should link library use to student learning outcomes at this level of detail.

Answering ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions of library impact

Understanding library impact means more than connecting the dots between use and expectations for student learning. Librarians need to know why students choose or choose not to use certain library resources and services. Librarians also need to know how students use libraries. What was important about a given service or resource? Where did the student encounter problems? Answers to ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions like these can support improvement efforts, resource allocation, and advocacy.

The Critical Incident Technique (CIT) is a research method well-suited to this type of problem.[11] Participants in CIT studies are asked to ‘place themselves in the moment when’ they were performing a task or participating in an activity. Questions and probes identify factors which influenced task success or failure. Analysis of reports from multiple participants provides a general understanding of the activity. The CIT has been widely used in information behavior and library impact studies over the past 30 years.[12]

Tuning outcomes: a method for communicating library impact

Communicating library impact on student learning in terms that resonate with stakeholders and customers is a significant challenge. The ULI protocol draws on the work of Tuning projects funded by the Lumina Foundation and the American Association of College and University’s VALUE rubrics[13] project to meet this need. This article focuses on the role of the Tuning outcomes in the ULI.

What is Tuning? Faculty, recent graduates, and employers work together in a Tuning project to create “a shared understanding” of what college graduates should know and be able to do. These projects generate ‘Tuning outcomes’ which represent discipline-specific competencies expected of graduates at the associates, bachelors and master’s degree levels.[14] Tuning outcomes can then serve as frameworks to guide assessment of student learning and communicate student competencies. Projects conducted in Indiana and Utah generated sets of learning outcomes for history majors.[15] The Utah State History department’s capstone rubric was created during the Utah Tuning project.

Research design for the 2011 ‘History capstone’ project

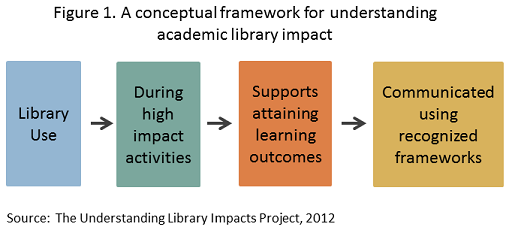

Figure 1 illustrates the logic of the ULI protocol: Students use library resources, services, and facilities during high-impact academic experiences, which support student achievement of associated learning outcomes. Those achievements can be communicated to stakeholders using recognized learning outcomes frameworks like the Tuning outcomes.

The protocol explores this assertion with two instruments: a critical incident survey and a learning activities crosswalk.

CIT Survey

The ULI protocol uses the CIT in a web-based questionnaire.[16] Students respond to the survey during the last month of the semester when they are taking the capstone or upper-level course. Originally prototyped in two interview-based studies,[17] the ULI survey asks students to ‘think back to a memorable time’ when they were working on their research project. The instrument identifies the library resources, services, and facilities students used during these projects and the ways in which this use contributed to or inhibited achievement. Open-ended questions gather ‘user stories’ that complement or reinforce other findings. The instrument closes with questions about affect (anxiety and confidence) and demographics.

Learning activities crosswalk

A research project in history consists of several overlapping stages, which I call learning activities.[18] These learning activities were identified in earlier studies and informed by Carol Kuhlthau’s model of the Information Search Process.[19] For instance, students begin their history projects by getting oriented to their assignment and the resources necessary to complete it. Next they choose a topic and develop a thesis. The student completes the project by building and communicating an argument using appropriate sources. Content analysis methods are used to construct a crosswalk between the activities and associated learning outcomes.

Selected results

Librarians, history faculty, and undergraduates at six colleges and universities in the U.S. participated in the ‘History capstone’ project in 2011. I refer to each institution as sites A, B, C, D, E, and F to preserve their anonymity when discussing results. Site A is a liberal arts university, sites B and F are private liberal arts colleges, site C is a master’s level public university, and sites D and E are public research universities.[20] Selected findings from the studies at site A and B have been reported previously.[21]

Upper-level and capstone courses in History were eligible to participate. Faculty members teaching these courses and librarians at each site helped facilitate the project. Faculty provided syllabi and other course learning outcomes documentation. Both librarians and faculty helped refine the instrument to meet local needs and add local questions. Finally, both groups helped with distributing survey URLs to students and encouraging their participation.

One-hundred-twenty-seven students reported ‘critical incidents’ about their experiences completing projects in these courses, making up a 34% response rate overall. Participants’ email addresses were used in a drawing for gift certificates at each study site. At the conclusion of the project, participating librarians and faculty received a summary report and a link to a web portal for reviewing detailed results.

Student respondents were largely of traditional college age (18-22) (87%). A majority worked at one or more jobs (74%) and lived off-campus (60%). Sixty-four percent of respondents were women, 85% were seniors, 94% were enrolled in college full-time, 9% were first generation students, and 17% reported transferring to their current institution.

Collections are king

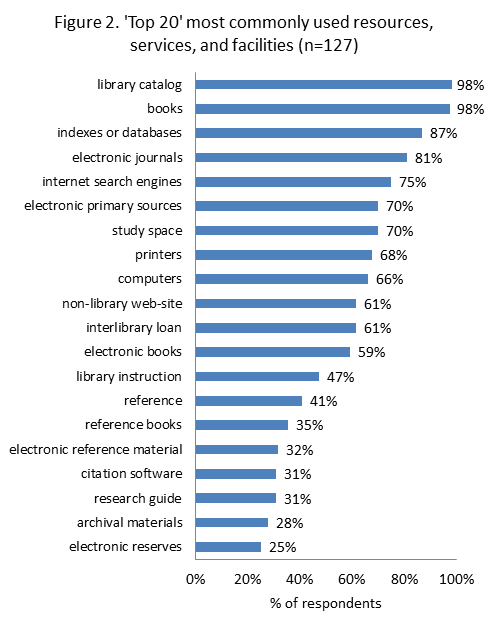

The ULI instrument asks students to reflect on four types of library use: electronic resources and discovery tools (referred to as electronic resources for brevity), traditional resources, services, and facilities or equipment. Students also identified their most important use in each category. The respondents reported using over 1,800 distinct types of library resources, services, and facilities during History research projects. The top 20 most common types of use are presented in figure 2. Students also reported over 2,100 ways that their ‘most important uses’ helped or hindered their achievement.

The document-centric nature of History projects likely accounts for the fact that the library catalog (98% of respondents), books (98%), indexes or databases (87%), and e-journals (81%) were the top uses among this cohort.

A full 77% of respondents said that books from the library were their most important traditional resource for the project. Of these respondents

- 61% reported books led them to relevant sources,

- 76.8% reported books provided the best information for their project,

- 56% reported books provided information not found elsewhere,

- 22.2% reported finding too much information in books, and

- 18.2% reported difficulties finding books in their libraries.

Primary sources in the form of archives (55%) and electronic primary sources (70%) were used by a majority of respondents. Non-library websites (61%) and internet search engines (75%) were used by a majority of students as well, but only 8 respondents reported either category as their ‘most important’ electronic resources.

Before we move on, I want to reflect on this point. Respondents used internet search engines, but most students claimed the library catalog (27.6%), library databases (21.3%), e-primary sources (19.7%), and e-journals (13.4%) were their ‘most important’ e-resources. These findings may be consistent with those reported by OCLC in a 2006 study which found that a majority of students reported starting their search with internet search engines but preferred library sources for their credibility and trustworthiness.[22]

There may be other influences at work. The Project Information Literacy (PIL) found that professors and instructors likely have a great deal of influence over student information behaviors as well. Alison Head and Michael Eisenberg reported in 2009 on a PIL study which found that 74% of their undergraduate student respondents reported using scholarly research databases because they “have the kind of information my instructor expects to see.” [23] In the ‘History capstone’ study, syllabi provided by participating faculty frequently set a minimum number of sources and page counts for papers. Some defined the types of primary and secondary sources acceptable for their papers and in other cases, clearly prohibited using unapproved ‘Internet’ sources. These factors may have driven students’ decisions to prefer library-provided resources over search-engines and non-library web-sites.

These findings are also consistent with those reported by William Wong and his colleagues in 2009 who found the most common reason among business and economics students for using ‘internal’ resources such as library acquired books and databases was the “quality and credibility of material and broad subject coverage.”[24] Further, these authors found that more experienced, expert users were more likely to use internal resources than inexperienced users. These phenomena could also be at work in this ULI study as 84% of the respondents were seniors and 78% were history majors. These are cohorts who ostensibly should be more experienced with resources for the discipline than younger students or non-History majors.

Services

The book-centered nature of these projects likely accounts for the fact that 61% of respondents used interlibrary loan (ILL) during their projects and 41% reported ILL was their most important library service.

About one-half of the respondents (52 %) reported using in-person services such as asking reference questions or requesting research consultations. Forty-seven percent said library instruction helped them during their projects. Yet only 14 (11%) reported using email or chat reference services.

Over 30% reported that library instruction (16.5%), reference (11%) or research consultations (5.5%) were their most important library services. Ninety-three percent of students who claimed library instruction as their most-important service reported that it helped them ‘learn about information sources for my project’.

Again, it is worth reflecting on these figures. Over one half of the respondents said they talked to a librarian in a reference transaction or a research consultation during these projects! What are other researchers reporting? OCLC found that 33% of students in a 2006 study reported using reference services monthly.[25] Alison Head and Michael Eisenberg in 2009 noted 20% of students reported they asked librarians for help when completing course-related research assignments.[26]

I won’t argue that these findings indicate reference trends are reversing or that my results are widely generalizable, but it is possible that students value in-person services more heavily during high-impact experiences like capstones. The influence of faculty and librarians cannot be overlooked here. A majority (93%) of syllabi examined during this project indicated a library instruction session was built into the curriculum for these courses. This likely encouraged use of in-person services among these respondents. Yet, correlation is not causation … future research is needed.

Use of library space and equipment

Ninety-four percent of respondents reported using library facilities and equipment. Seventy percent used library space for studying or research, 68% used library printers, and 66% used library computers. Among these respondents:

- 51% reported valuing quiet study space; but 11% had problems with noise.

- 80% reported library computers provided access to productivity software and 53% reported library computers allowed them to access needed information.

- 13% used space for collaborating with peers, yet half of these students had a hard time finding space to accomplish this task.

Use by learning activity

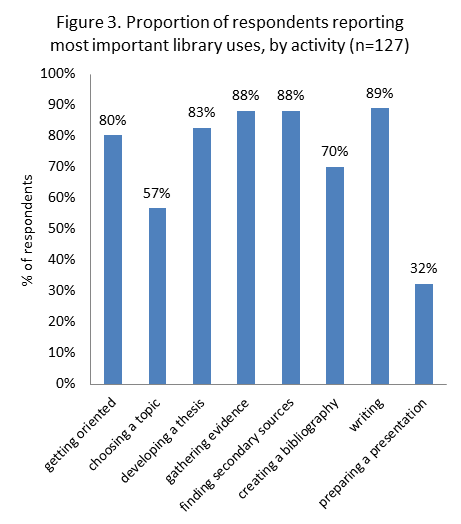

Students completing the ULI survey identified the learning activities during which they used their most important library resources, services, or facilities. As seen in figure 3, at least 80% of respondents reported using their most important library resources, services, or facilities during 5 of 8 learning activities: getting oriented, developing a thesis, gathering evidence, finding secondary sources, and writing.

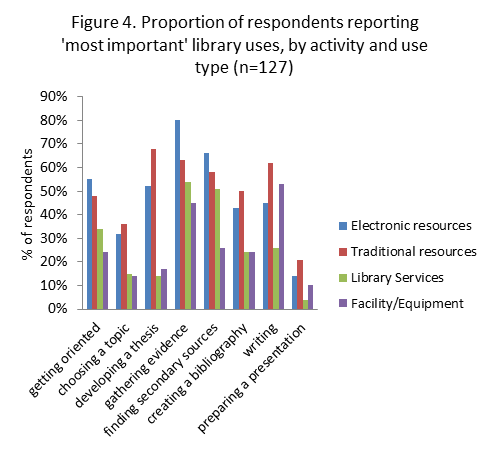

We can now drill down into these results. Figure 4 presents the proportion of students using their ‘most important’ resources, services, and facilities during each activity. Students could select more than one activity per use. Because we are focusing on the ‘most important uses’ this chart only displays data about 462 of the 1,806 distinct uses (25.6%) named by students. For those of us who have worked with students on the reference desk, the variations in use by learning activity are not necessarily surprising.

“Please think back to a challenging time during the project …”

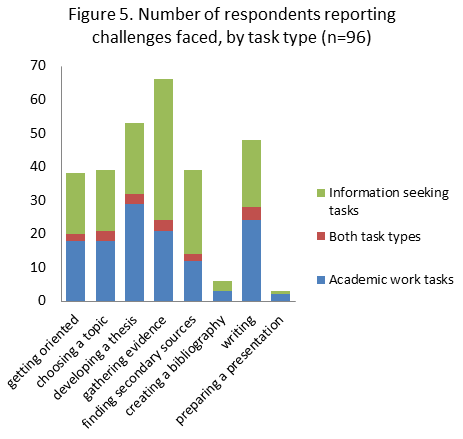

Open-ended questions in the CIT survey encourage respondents to elaborate on their experiences. One set of questions explores a ‘significant challenge’ faced by the student during their project. Ninety-six students provided usable responses to this series of questions.[27]

Fifty-six percent of these challenges were related to information seeking such as selecting tools, finding primary and secondary sources, and interpreting information, such as:

“It can be difficult to identify the best database to consult.”

“I was having a difficult time locating primary sources.”

While this was a ‘library’ assessment project, students identified non-library challenges as well. Forty-one percent of respondents reported challenges related to academic work tasks like choosing a topic, developing a thesis, and building an argument:

“I had trouble narrowing my topic to a feasible argument.”

“My biggest problem was corroborating my own ideas with an established scholar’s”

Figure 5 illustrates the number of respondents reporting challenges by task type and the learning activities in which the challenge was faced. One third to one half of the respondents who answered these questions faced their challenges in the earliest stages of the project with a peak during the ‘gathering stage.’ Forty-eight students (50%) then reported facing a challenge during the act of writing.

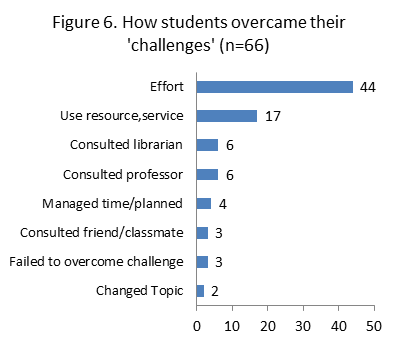

Sixty-six students reported how they overcame their challenges. As shown in figure 6, forty-four (66%) overcame their challenges through effort, such as “I dove into primary material” or “Brute force–tried new search terms until I got what I wanted.” Seventeen (26%) used a specific library resource or service such as interlibrary loan, or JSTOR. Twelve out of 66 (18%) respondents asked for help from a librarian (6 respondents) or their professor (6 respondents) when overcoming their challenge.

Bringing it all together … linking library use to student learning

The learning activities crosswalk links library use with learning expectations associated with student projects. This is illustrated using the learning activities used in the ULI survey and student learning outcomes defined in the Utah State University History department’s capstone rubric provided in table 1.

For instance, a student who is ‘choosing a topic’ or ‘developing a thesis’ is performing activities related to ‘framing a historical question’ (outcome 2). A student ‘gathering primary sources as evidence’ would be demonstrating the ability of ‘evaluating and analyzing primary resources’ (outcome 3).

These connections can be illustrated for groups of students using results from the study.

- 46% of respondents at Site F used their most important traditional resources (principally books) when choosing a topic; 88% of respondents at Site A and 64% of respondents at Site C used their most important traditional resource when developing a thesis.

- These are times when students develop and demonstrate the abilities of

- framing a historical question (rubric outcome 2) and

- evaluating and analyzing primary and secondary sources (outcomes 3 and 4)

- These are times when students develop and demonstrate the abilities of

- 73% of respondents at Site D, 75% of respondents at Site E, and 92% of respondents at Site B used their ‘most important’ electronic resources (mostly the library catalog, e-journals, digital primary sources, and indexes and databases) when gathering evidence to support a thesis.

- This is a time when students develop and demonstrate the abilities of

- evaluating and interpreting primary sources (outcome 4) and

- employing primary sources appropriate to the informing thesis (outcome 5).

- This is a time when students develop and demonstrate the abilities of

- 54% of respondents at Site E, 64% of students at Site D, and 67% of students at Site F used their ‘most important’ facility or equipment (including study space and library computers) during the activity of writing. This is a time when students develop and demonstrate the abilities of

- organizing an argument (outcome 7),

- citing evidence (outcome 8), and

- using proper writing mechanics (outcome 9).

Results for individual students

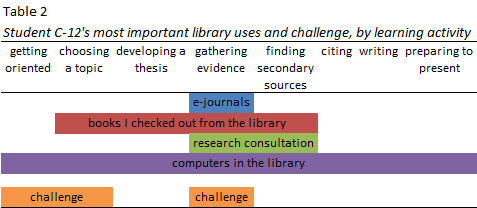

The ULI ‘History capstone’ results for individual students illustrate how the crosswalk works and how the qualitative and quantitative data complement one another. For instance, student C-12 is aged 23-30, a history major, and a 5th year senior attending college full-time at site C, a Master’s level public university. She works 2 jobs and holds an internship. She used 24 types of library resources, services, and facilities when working on her project including reference services and a research consultation.

At the beginning of the CIT survey, student C-12 reflected on the learning objectives associated with her project. Her observations mirror the rubric outcomes of ‘employing a range of primary sources appropriate to the paper’ (outcome 5):

“… When it came to the paper she [my professor] wanted us to work with many sources learning how to decide which ones are the best to put towards our paper. She also wanted us to learn how to become better writers.”

Student C-12 reported that electronic journals, books, a research consultation, and computers in the library were the most important resources, services, and facilities to her during the project. Table 2 demonstrates the learning activities that these uses supported.

Student C-12 reported a challenge narrowing her topic, an issue which is related to the Utah learning outcome ‘framing a historical question’ (outcome 2). She also had concerns about finding enough resources, a task related to the Utah rubric outcome ‘employing a range of primary and secondary sources’ (outcomes 5 and 6):

“Narrowing down my topic as much as the teacher wanted. I was concerned that I was not going to be able to find enough information and write such a big paper on a narrow topic.”

This challenge occurred during the getting oriented, choosing a topic, and gathering evidence stages of the project. She overcame this challenge by scheduling a research consultation with a librarian during the gathering evidence and finding secondary sources learning activities:

“[I] did a [research consultation] session and worked with a librarian to find many more sources through different databases and journals.”

She was anxious before and during the project, but reported improved confidence after completing the project. Respondents like her, who used research consultations and reference services, were more likely to report increases in confidence than those who did not.[28]

Later she wrote that she achieved the learning objectives associated with the paper:

“I think I did. If I could do this project again I would try to not wait till so far at the end to put the paper together.”

A framework for examining library impact

These selected results demonstrate how the ULI protocol provides a framework for exploring library impact on student learning. Focusing on the learning activities associated with high impact activities like the capstone generates a natural pathway for linking library use to expectations for learning. In the Value of Academic Libraries Report,[29] Megan Oakleaf called for new work connecting library use to student achievement results. The ULI protocol is well-positioned to meet this challenge.

Asking ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions with the Critical Incident Technique, generates rich information about the ways students use the library to meet their learning goals as well as illuminating the problems they have. Library managers can use these data to support internal improvements or resource allocation decisions. Finally, aligning library assessment with faculty-led initiatives like Tuning will make it easier for libraries to join campus conversations regarding student learning.

Threats or opportunities?

These are challenging times in higher education. Expectations are running high and demands to control costs continue to mount. Libraries and other campus units can take a ‘wait and see’ stance in case the ‘accountability clouds’ blow over. I think this is a risky move. I hope libraries will be proactive by examining library impact and sharing their findings. Doing so will bring libraries into important campus conversations about student learning and advance our collective knowledge in this area.

Next steps for the ULI protocol

Planning is underway for the next round of ULI studies. In each project, the ULI instruments will be adapted for specific academic majors, to reflect each library’s specific service offerings, and to accommodate ‘custom local’ questions. The next round of ULI projects will build on current work in two ways. First, the ULI protocol will be tested in new disciplines such as the social and life sciences in addition to more studies in the field of history or other humanities disciplines. Second, the ULI model will be adapted to include existing data sources such as results of student assessments in the form of rubric scores, course grades, or other measures.

Participating in a ULI project is one way to help move the library impact agenda forward. To get involved or learn more, please contact me at The Understanding Library Impacts Project website.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Ellie Collier, Hilary Davis, Nathaniel King, and Jennifer Rutner for reviewing drafts of this article and for their valuable insights and suggestions. Thanks again to Hilary for her assistance in preparing the final version. I also want to acknowledge the anonymous contributions of faculty, librarians, and students who facilitated and participated in the project.

[1] Radford, A.W., Berkner, L., Wheeless, S.C., and Shepherd, B. Persistence and Attainment of 2003–04 Beginning Postsecondary Students: After 6 Years (NCES 2011-151), 2010. U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Table 3.

[2] OECD. Education at a glance 2011: OECD Indicators, 2011, Chart A1.1, p. 30.

[3] Lumina Foundation. “Our Goal,” 2011.

[4] The costs of attending college in the U.S. increased 4.9% annually from 2000 to 2009. College Board. Trends in college pricing, 2009.

[5] Oakleaf, Megan. The Value of Academic Libraries: A comprehensive research review and report for the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL). Chicago: ALA., 2010. Executive Summary, p. 5

[6] American Library Association. Association of College and Research Libraries. Standards for libraries in higher education, 2011. American Library Association, ACRL, College Libraries Section.

[7] Poll, Roswitha & Payne, Philip. Impact measures for libraries and information services. Library Hi Tech, 24(4) (2006):547-562., p. 549.

[8] Kuh, George D. High-Impact Educational Practices: what are they, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges and Universities, 2008.

[9] McInerney, Daniel J. “Rubrics for history courses: lessons from one campus.” Perspectives on History 48(7) (2001):31-33, p. 33

[10] Used with permission of Dr. Daniel McInerney, Department of History, Utah State University.

[11] Butterfield, L.D., Borgen, W.A., Amundson, N.E., & Maglio, A.T. Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954-2004 and beyond. Qualitative Research, 2005, 5(4) 475-497.

[12] See for example Radford, Marie L. The Critical Incident Technique and the Qualitative Evaluation of the Connecting Libraries and Schools Project. Library Trends, 55(1) (2006):46-64; Marshall, Joanne G. The impact of the hospital library on clinical decision making: the Rochester study. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 80(2) (1992):169–78; Tenopir, Carol & King, Don W. Perceptions of value and value beyond perceptions: measuring the quality and value of journal article readings. Serials 20(3) (2007):199-207.

[13] The American Association of Colleges and Universities recently produced what it called the Essential Learning outcomes as part of its LEAP (Liberal Education for America’s Promise) project (2007). AA C & U identified a range of broad abilities and knowledge that undergraduate students majoring in all disciplines should master. The VALUE project (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education) The American Association of Colleges and Universities sponsored work that identified 15 VALUE rubrics to guide local assessment efforts. See Association of American Colleges and Universities (2007). College Learning for the New Century A report from the National Leadership Council for Liberal Education and America’s Promise, Washington, DC: AAC&U. http://www.aacu.org/leap/documents/GlobalCentury_final.pdf and Rhodes, Terell L. “VALUE: Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education.” New Directions in Institutional Research. Assessment supplement 2007, (2008): 59-70 for more information.

[14] Lumina Foundation. Tuning USA, 2009.

[15] Indiana Commission for Higher Education. Tuning USA Final Report: The 2009 Indiana Pilot, 2010. and Tuning USA Final Report – Utah, November 18, 2009. The Lumina Foundation has funded ‘Tuning’ projects in other disciplines as well. For instance, the project conducted in Indiana focused identified outcomes in History, Chemistry, and Education. The Utah project generated Tuning outcomes in History and Physics. A project conducted in Minnesota Tuned Biology and Graphic Arts. The Lumina Foundation has funded two new Tuning projects in the last six months. The Midwest Higher Education Consortium is Tuning Psychology and Marketing in Illinois, Indiana, and Missouri and the American Historical Association is beginning a nationwide Tuning project in the field of history.

[16] The Qualtrics online survey application was used to gather responses for this study, http://www.qualtrics.com.

[17] Rodriguez, Derek A. Investigating academic library contributions to undergraduate learning: A field trial of the ‘Understanding Library Impacts’ protocol. 2007; Rodriguez, Derek A. “How Digital Library Services Contribute to Undergraduate Learning: An Evaluation of the ‘Understanding Library Impacts’ Protocol”. In Strauch, Katina, Steinle, Kim, Bernhardt, Beth R. and Daniels, Tim, Eds. Proceedings 26th Annual Charleston Conference, Charleston (US), 2006.

[18] Learning activities used in the History capstone project in 2011 included: getting oriented, choosing a topic, developing a thesis, gathering primary sources as evidence to support my thesis, finding secondary sources, creating a bibliography, writing, and preparing an oral presentation (sites C, D, E, and F). The crosswalk was conducted using content analysis of syllabi, program-level documentation of expectations for student learning outcomes, and products of the Indiana and Utah Tuning projects. Multiple coders assisted with content analysis tasks. Inter-coder agreement was assessed through the use of Krippendorff’s alpha reliability coefficient. See Hayes, Andrew. F., & Krippendorff, Klaus. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1 (2007):77-89.

[19] Kuhlthau, Carol C. Seeking Meaning: A Process Approach to Library and Information Services. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2004, p. 82. Kuhlthau’s model includes six stages: Initiation, selection, exploration, formulation, collection, and presentation.

[20] Institutional control, type, basic Carnegie classification, and size of the student body for each site are provided for each site. Site A: Private Liberal Arts University, Master’s S, (5,000+ students); Site B: Private Liberal Arts College, Baccalaureate College(Arts & Sciences), (<2,500 students); Site C: Public University, Master’s L, (15,000+ students); Site D: Public Research University with high research activity (RU/H), (25,000+ students); Site E: Public Research University with very high research activity (RU/VH), (30,000+ students); Site F: Private Liberal Arts College, Baccalaureate College (Arts & Sciences), (3,000+ students). Three of the institutions are in the southeastern U.S., two are in the Midwest, and one is in the northeastern U.S.

[21] Rodriguez, Derek A. “The ‘Understanding Library Impacts’ protocol: demonstrating academic library contributions to student learning outcomes in the age of accountability: A Paper presented at the 9th Northumbria International Conference on Performance Measurement in Libraries and Information Services, York, England, August 23, 2011. Proceedings preprint

[22] OCLC. College Students’ Perceptions of Libraries and Information Resources: A Report to the OCLC Membership. Dublin, Ohio, 2006.

[23] Head, Alison J. & Eisenberg, Michael B. “Lessons Learned: How College Students Seek Information in the Digital Age.” Project Information Literacy First Year Report with Student Survey Findings, University of Washington’s Information School, 2010, p. 27.

[24] Wong, William, Stelmaszewska, Hanna, Bhimani, Nazlin, Barn, Sukhbinder. User behaviour in resource discovery: Final report. 2009, p. 79.

[25] OCLC. 2006, 22.

[26] Head & Eisenberg, 2009, 23

[27] Multiple coders categorized qualitative responses and inter-coder agreement was assessed using Krippendorff’s alpha reliability coefficient.

[28] Students were asked questions about their anxiety and confidence before and after the project using a 5-point Likert scale. Students who used research consultations (χ2=19.5847, df=6 p=0.0033) and reference services (χ2=14.695, df=6 p=0.0228) were more likely to report increases in confidence in their research skills than those who did not use these services.

[29] Oakleaf, 95.

Pingback : New Answering questions about library impact on student learning – Stephen's Lighthouse

Pingback : Around the Web: Decline of the library empire, Libraries' impact on student learning and more : Confessions of a Science Librarian

Pingback : Common Core | Pearltrees

Pingback : Academic news roundup: assessment, active learning, and online ed | Ink and Vellum

Pingback : regarding “library impact on student learning” « studiumlibrarios