The Digital Public Library of America: Details, the Librarian Response and the Future.

In brief: The Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) launched last week. This article attempts to tease out the librarian response to DPLA and explore what it means for the future of the library in popular imagination, as well as in our field. I describe the what, who, and how of DPLA and ask, after two years of work on the project, what can librarians can expect from DPLA and what does DPLA expect from us? This article concludes by proposing that librarians want four things from DPLA: Advocacy, Inclusion, Investment and Clarity.

Introduction:

Two years ago I took a gigantic leap of professionalism and subscribed to my first mailing list ever, the Digital Public Library of America Discussion list. The concepts and ideals behind the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) were just coming into shape and I was so excited about it that I went so far as to agree to have it inundate my email inbox. Not long after, I wrote a post about DPLA for the blog, HackLibrarySchool, in which I spelled out some of my interest in the project, as well as some important questions to consider. Quoting myself, “the reason [DPLA] feels so important, is that a group of capable and brilliant folks from a variety of reputable institutions (libraries, institutes, universities) have identified a need, and have initiated a grand idea to address that need.” Now, with the launch of DPLA, I’d like to provide a quick overview of how the project has grown, where it is going, and most importantly, what it means for librarians. Following a brief introduction to the project, I survey the literature about it, introduce some questions and issues with which the DPLA still needs to contend, and close by suggesting a possible collaborative future including the work we do in large-scale projects like this.

What is the Digital Public Library of America?

The concept of a national public library is not new. Traditionally, the Library of Congress (LOC) is seen as the national library of America, for good reason, but the LOC’s stated mission is primarily to serve the research needs of the U.S. Congress. With the wealth of digital information and the tools finally becoming available, extensible, and accessible, governments around the globe are beginning projects to create “digital libraries” of their heritage and history. In fact, DPLA planning documents mention the national libraries of Norway, The Netherlands, and South Korea as models to explore.

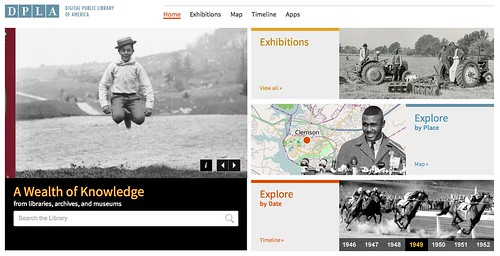

There are three layers to the project: a portal, which is the public-facing website with search functions; a platform, the code underlying the technical infrastructure, which is open source so that others can build on top of it; and a partnership, which pairs this project with libraries, museums, archives, funders, universities, schools, and other institutions, to advance the mission of libraries in providing access to information. The DPLA, in its current incarnation, is primarily a metadata repository that pulls open data from cultural heritage collections at multiple institutions and centralizes it. As stated in DPLA’s mission, “The DPLA is leading the first concrete steps toward the realization of a large-scale digital public library that will make the cultural and scientific record available to all.”

While collecting numerous digital objects into one point of access may seem idealistic, DPLA is taking practical steps in a sensible direction. Building on the work of related projects like HathiTrust, Internet Archive, and Europeana, the Digital Public Library of America intends to capitalize on previous and ongoing digitization projects by letting many digital objects be discoverable on one platform. However, there are numerous things to consider when launching a digital project with regards to the target audience/participation, scope of content, finances/business models, governance, legal issues, and technical aspects. Luckily, those were the exact areas that the DPLA identified as “workstreams,” in which qualified and competent professionals worked for the past two years. Those workstreams have now been consolidated into committees that will continue to inform the development of the project.

The focus on cultural heritage collections, an early example of which can be seen in Leaving Europe —a jointly curated DPLA/Europeana virtual exhibit—allows DPLA to begin quickly with content that is already easily accessible. John Palfrey, of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society and lead spokesperson for DPLA, states, “In its first iteration, the DPLA will combine a group of rich, interesting digital collections, from state and regional digital archives to the special collections of major university libraries and federal holdings. DPLA will demonstrate how powerful and exciting it can be to bring together our nation’s digitized materials, metadata (including catalog records, for instance), code, and digital tools and services into an open, shared resource” (Palfrey, 2013). There has been a great deal of discussion about including books (e- or otherwise), orphan works, scholarly materials in open access institutional repositories, and other readily available digital corpora. Going forward, these other content types may be considered for inclusion in the DPLA, though the version of the DPLA that launched last week includes only metadata related to cultural heritage objects.

Who is involved in DPLA?

Committees

Conversations about a broad, multi-institutional collaboration on a national digital library in America began at an October 2010 meeting of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, culminating in a Steering Committee. In December 2010, the Berkman Center for Internet and Society convened a meeting that would produce the DPLA Secretariat, directed by Maura Marx of Open Knowledge Commons. With the foundations laid, these teams began to define the details, possibilities, and grand ideals of the Digital Public Library of America. The work of the Steering Committee and the Secretariat was invaluable to the early progress of DPLA, in addition to the individuals listed below.

Robert Darnton

“A Library Without Walls,” a piece written by Robert Darnton for the New York Review of Books, is generally seen as the inception of the DPLA. Darnton is a historian and the Director of Harvard University Libraries. He has remained involved in the conception and governance of DPLA, serving on the Steering Committee as well as being a public voice for the project from time to time.

John Palfrey

A director at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, Palfrey has been the most vocal and visible proponent of DPLA since early planning meetings, and currently serves as President of the DPLA Board of Directors. He previously directed Harvard’s Law School Library and is now the Head of School at Phillips Academy in Andover. Palfrey’s book Born Digital may have run across your desk at some point.

Dan Cohen

Only recently announced as Executive Director of DPLA, Dan Cohen brings years of experience leading the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (CHNM) on high-profile digital humanities projects like Zotero, Press Forward, and Hacking The Academy. Cohen, a digital historian, brings – as the Library Loon has pointed out – public presence, authority, and gravitas to the position. ((The Library Loon’s article “DPLA and the so-called ‘Feral Librarian’ is a must read for insight on Dr. Cohen’s role in the project.))

Emily Gore

The first official employee of DPLA, Emily Gore has worked in libraries and technology for 12 years. As the Director of Content, Gore oversees the “what” that will become DPLA’s collections. She was most recently employed as the Associate Dean of Digital Scholarship and Technology at Florida State University and is a 2011 graduate of the Frye Leadership Institute. ((Full disclosure: Emily hired me into my current position and was my direct supervisor for eight months before joining DPLA.))

Amy Rudersdorf

As DPLA’s Assistant Director of Content, Amy Rudersdorf “is responsible for digitization partnerships and related workflows, metadata normalization and shareability, and community engagement to promote the DPLA as a community resource.” She is a leader in digital preservation and also teaches metadata and digital libraries for graduate programs in library and information science.

Partner Organizations

From the very beginning, DPLA was lent credence due to the partner organizations that signed on in support of the initiative. The Smithsonian Institution and the National Archives pledged content partnerships early on, and in recent weeks the New York Public Library, ArtSTOR, the Biodiversity Heritage Library, and The Library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have all signed on as well. The fact that there is an open invitation to “join” allows DPLA to build a coalition that will draw more interest and investment. A full list of the current partner organizations is available on the website. In addition to content, DPLA secured funding from the Sloan Foundation, the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS), the National Endowment for the Humanities and others, marking it as a worthy investment for prestigious funding organizations.

The Public (Me and You and Everyone We Know)

Early conversations surrounding DPLA included worries that a project of this scale might not include enough people from the library community. These concerns were addressed in multiple ways, which I will illuminate later in this article. Primarily, the project extended multiple calls for participation, including a public wiki, the aforementioned listservs, open workstreams, Appfests, and Beta Sprints, and many librarians and others had a hand in creating what it now is. A Get Involved page invites continued participation and asserts the DPLA’s insistance on this project continuing to be built as a community.

The prevailing zeitgeist of open, collaborative, “public,” project-based, and community-built and -owned initiatives serves the DPLA well. Margaret Heller, writing for ACRL Tech Connect, reported from DPLA Midwest, “I found the meeting to be inspirational about the future for libraries to cross boundaries and build exciting new collections. I still have many unanswered questions, but as everyone throughout the day understands, this will be a platform on which we can build and imagine” (Heller, 2012). In a similar spirit to the crowdsourced participation of Wikipedia, “The DPLA… [is] very leanly staffed with tons of volunteers,” says John Palfrey. Thousands of librarians, technologists, students, professors, curators, and administrators worked to build the project over two years through discussions and hackathons. “This may feel like a utopian project,” Palfrey continues. “If we don’t aim for what we want, we’ll sell ourselves short. We need to get in front of this mob and call it a parade” (Borman, 2012).

What DPLA isn’t

DPLA is not a public library, a content repository, or a threat to traditional library services.

In defining a massive project of this scope, calling it a “public library” has led some in the profession to dismiss it outright, or at least question its motives. The Chief Officers of State Library Associations went so far as to issue a resolution [PDF] that the name be changed. How could a well-funded, Harvard-based, academic-focused, non-librarian-led thing purport to call itself a “public library”? The inclusion of “public” in the title is important in defining the role of this organization in our country’s mind. People understand that the items in a public library’s collection belong to them and are available for their use. So it should also be with DPLA, Dan Cohen wrote, claiming that public libraries engender trust, localness, relevance, and familiarity. The ultimate decision to call the project the Digital Public Library of America was a conscious one, reflecting an intention to make it known that the public are invited and expected to claim ownership of the collection. It is not a public library in the same way that the Brooklyn Public Library is, yet the goals and hopes of the organization are the same.

As it is now, content (digital objects/files) from digital libraries that partner with DPLA will remain with the institutions. Only the metadata about those objects will be harvested for display and discovery from “hubs” like the Smithsonian Institution or the Digital Library of Georgia (the full list of hubs is available online). This approach accomplishes two things at once: 1) it utilizes the “open data” that is becoming more essential for the discoverability of online digital collections, and 2) it is creating a model by which potential future “donors” can participate in the DPLA. Digitization efforts at regional, state, or local institutions will have a single point of access to make their cultural objects and artifacts available to their communities, the general public, and researchers. The motivation for including your library’s digital collections in the DPLA is the increased discoverability and cross-collection connections that will be more evident when searching inside one aggregated platform.

It is important to remember that we (DPLA and the field of librarianship, writ large) are on the same team, working diligently to provide access to information. It is for the users, not for us. DPLA has the potential to be an additional resource for the library community to connect our patrons with the wealth of knowledge and information we protect and preserve. Seeing it as anything but an incredible resource would be a disservice. Peter Murray, in a report from the Audience and Participation Workstream meeting at George Mason University, lists the variety of groups that this resource might affect. His list includes “Casual Searchers, Genealogy, Hardcore Enthusiasts, Wikipedia/Open Source Folks; info nerds, Small business/startups, Writers/Journalism, Artists, Students, Public School Teachers, Home schoolers, Scholars, Other Digital Libraries, State Libraries, Public Libraries/Public Librarians, Museums, and Historical Societies” (Murray, 2012). Approaching the DPLA as a resource for our users, in combination with the long list of skills and competencies that librarians of all types possess, will serve to strengthen our shared goal to enlighten and inspire.

What librarians think of DPLA

Nearly absent from taking a leading role in DPLA is the American Library Association. Aside from the occasional editorial in American Libraries magazine, time and space at annual conferences for DPLA-based discussions or presentations, and the current president of ALA, Maureen Sullivan, sitting on the Marketing and Outreach committee, there has not been any significant visible support for the project in the multitude of committees, offices, round tables or divisions of ALA. A statement from Alan Inouye, director of ALA’s Office for Information Technology Policy, expresses nominal interest, without much substance, saying, “ALA is following the development of the DPLA with great interest and optimism… The very creation of the DPLA enterprise has raised the profile of libraries in the digital age… ALA appreciates the ambitious and perhaps daunting scale and scope of the DPLA undertaking” (Cottrell, 2013). Representing some significant portion of librarianship, with membership at 60,000, ALA appears to have purposefully distanced itself from active participation in the DPLA for reasons that have yet to be disclosed.

The Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) is also largely missing from the DPLA infrastructure. Perhaps indicative of their thoughts on the project, the OCLC report, “America’s Digital Future: Advancing a shared strategy for digital public libraries,” vocalizes desires for public library involvement in the creation of a national library. The opening pages of the report, based on a meeting at Los Angeles Public Library, state,

Library leaders contributing to this discussion agreed: many public librarians feel behind in the evolution to a more digital library. Participants noted that academic and research libraries have made more strides in shaping a digital future, evidenced in the major projects and new efforts of organizations such as the HathiTrust. Participants also noted that the rapidly evolving digital activities in the commercial sector, such as e-books and e-book reading devices, are “changing the game” for public libraries, and that public libraries have been too slow in generating a national, concerted plan (De Rosa, et al, 2011).

Early criticisms of DPLA included charges that public libraries had not been consulted or included in the planning or leadership of the project. To the contrary, everyone involved in DPLA— including Robert Darnton, John Palfrey, Emily Gore, and Dan Cohen—have made it clear that DPLA is meant to connect people with the local and public institution, not direct them away from it. Palfrey goes so far as to urge libraries that their involvement is fundamental and necessary. He writes that “libraries must make a digital shift, charting a course that is different from our present direction. No one should fear (or act like) libraries are going away, but we need to continue to strive to change the services they provide and to build the case for them in a digital era” (Palfrey, 2013).

David Rothman, founder of TeleRead and LibraryCity.org, has been vocal about approaching this project cautiously, especially in regards to K-12 education and school librarians, who are intended as a primary target of this initiative. His editorial in the Chronicle of Higher Education, titled “It’s Time for a National Digital-Library System: But it can’t serve only elites,” mentions the extreme focus on humanities-based content, to the exclusion of scientific, medical, mathematical, business, and vocational collections. He also accuses DPLA of engaging in high-academic rhetoric, “while ignoring, for instance, reference services, user communities, and grass-roots content like oral histories” (Rothman, 2011). Some of his concerns (a breadth of content beyond cultural heritage objects and flexible technology) are now recognizable goals of DPLA’s continued growth. Rothman’s suggestions that DPLA remain invested in literacy and the digital divide are also well-taken; these issues will remain at the forefront of libraries regardless of a national digital library’s claims of access for all.

Nate Hill, Assistant Director of the Chattanooga Public Library, offers a different take, proposing that DPLA offers public libraries a reformative path.

I think that the DPLA is a great opportunity for libraries to shift their focus to supporting a different set of activities in our buildings… creation activities: the production of new knowledge for personal growth and sometimes even the public good. The future of public libraries lies in supporting creative endeavors in their local community and empowering the patrons to contribute their creative work back to the community or to the whole world via the internet… There is no other institution doing this work, and public libraries are best situated to fill the gap (Hill, 2011).

The evolving mission of the library is a discussion that flows across interdisciplinary lines and Hill encapsulates it nicely. His assertion could as easily be applied to academic libraries. Since DPLA is a concept of an academic librarian and the investment of many in the higher education enterprise, it seems the research library community has more easily embraced the project. This is in no small part due to the focus on research and access to primary sources that has led academic libraries, museums, and historical societies to actively pursue digitization projects, content which can easily be ingested to the DPLA version 1.0. The DPLA will play an important role in the ongoing transformation of “The Library” from a strictly consumptive space to a broadly creative space due to its open infrastructure, collaborative ethos, and hopefully even involving the public in the creation and curation of content.

In late 2011, Molly Raphael, at the time President-Elect of the American Library Association, echoed Hill’s opportunist bent, albeit cautiously. Listing “the issues that generated the most passionate discussions,” she writes (adding her own thoughts in parentheses):

● Should we only consider open access, or should we think about the possibility of tiered access? (My take: Open access seemed to rule the day.)

● What is being conveyed by including “public” in the name? (My take: Let’s not get too bogged down on the name, but we need to be careful about what we convey by the words we use.)

● Whose voices were we missing, such as school librarians or others, and how do we make sure that the tent is “big” and welcoming? (My take: The tent kept getting bigger as more people were invited, but we knew that we needed to consider the question: “Who is not in the room that should be in the room?”)

● How should we approach the challenge—look for low-hanging fruit, such as material already in the public domain? Seek to tackle the issue of orphan works, where much of the content that researchers want can be found? Build on the work of those who are already building large digital libraries? (My take: We have opportunities to build more coordinated access to much that is already available digitally, but let us not lose sight of the importance of access to those sources that have legal complications.)

● How can we be sure that we put needed focus on metadata and APIs and not just on capturing the content? (My take: Thank goodness this effort is being driven by librarians and researchers who care about the keys to access.)

● How important is it to tackle copyright revision? Do we have the tools we need without thinking about that now? (My take: This is a tough one. Opinion about what we can or can’t do under current law is divided, but generally most agreed that we would need to press for copyright revision eventually, particularly for orphan works) (Raphael, 2012).

Many of the issues Raphael lists are similar to the current focuses of the research and academic librarian community: copyright, re/use of metadata, open access, and the “big tent” approach to building and consensus-making, are defining the culture of higher education. In contrast to the aforementioned public library considerations, there has been much less of an active response from academic librarians. Several research libraries have joined as partners, expressing obvious support at the institutional level, but individuals have been less forthcoming. Perhaps this is due to the fact that academic libraries are more deeply invested in access to primary source materials and are more agile in approaching technological changes, as that seems to be the trend in higher education. The academic library conversation, then, is more topic-specific (ex. copyright) than focused on large-scale projects. Or, academic libraries are approaching the project with distanced interest, beholden first to the goals of their school and the bureaucracy that often entails. College and Research Libraries News briefly mentioned DPLA in its Top Trends of 2012 report as a project worthy of attention. That report lists trends that include digital preservation, data curation, and scholarly communication, which are all related to the work and goals of DPLA.

Finally, for a personal perspective on DPLA, Andy Woodworth provides a specific sense of why this massive project may have yet to breach the consciousness of the larger library community. He writes,

“The Digital Public Library of America seems like the Manhattan Project: it’s massive, complex, has great minds from many different fields working on it, and not many people know about it. Not because it is secretive [and] not for a lack of exposure… It just hasn’t arrived at the tipping point of intruding on the lives of librarians on their home turf. That’s where I find myself: how will this affect my community?” (Woodworth, 2012.)

As open and inviting as DPLA has been, they have yet to purposefully and single-mindedly answer that question: What are the implications of DPLA for the library community? How does this affect our patrons? The distance between large-scale initiatives and the insularity of library work (either public, academic, school, or special) is a singular factor in librarian buy-in. Woodworth continues, “From my perspective, the DPLA is at the opposite end of action spectrum for digital content and digital rights from me. We are both working towards the same goal, but I am operating from the grassroots level while it operates from a top-down perspective.” Following the launch of DPLA last week, Library Journal compiled an article titled “Librarians respond to DPLA launch” including opinions from Jason Griffey, Jessamyn West and others, ranging from excitement for the open API to noticeable errors in legacy metadata.

What librarians want from DPLA

Themes from the various responses to the DPLA can be condensed into four broad areas that I’d propose encapsulate what librarians want from the Digital Public Library of America: Advocacy, Inclusion, Investment, and Clarity on why we should participate and how we can get our communities involved.

Advocacy

The political climate in which we function requires consistent messages, constant efforts, and collective representation. If DPLA intends to function as a highly recognizable (“public”) facet of our ecosystem, it must advocate at the highest levels for the needs of the future library. Dan Cohen, representing the interests and influence of many behind the scenes at DPLA says, to that point, “I see a strong advocacy role for the DPLA, to say that a better balance is needed in the twenty-first century, so that the landscape for reading and research isn’t further circumscribed and hindered by digital friction” (Enis, 2013). It is the hope of the library community that this will ring true as DPLA moves forward.

Inclusion

Libraries want to be included in the construction of a national digital library. Again, DPLA has worked to ensure that this occurs, and as more libraries and librarians become aware of this project, I hope that time, energy, and resources will be devoted to participating in this grand experiment. Already organizations like the American Council of Learned Societies are offering positions for post-doctoral fellows to work on the project. I would call on the library community to proactively pursue inclusion, and encourage our professional organizations to consider offering similar opportunities (fellowships, internships, scholarships) to prove our vested interest in working together to build the DPLA.

Investment

DPLA will have to prove its support for existing institutions. As a starting point, providing a portal into the work of others is an efficient strategy, but as we all know, there’s much more where that came from. How does the Digital Public Library of America plan to utilize their funding, resources and momentum to reinvest in, and enrich, the collections and communities that are not yet digital?

Dan Cohen: “I want the American public to know that the DPLA will be the place to go to find documents and images about their hometown, scanned and curated locally; to be able to pull out their smartphone, launch an app powered by DPLA’s data, and take an impromptu walking tour of the hidden past of their current location; to see the DPLA’s open and free content spread across classes from kindergarten to graduate school; and many other exciting possibilities enabled when formerly disparate collections are knit together—entirely new kinds of searching, discovery, and learning. Forget the massive technical infrastructure; if the DPLA can ignite that wonder that only libraries can provide, we will have done our job” (Enis, 2013). ((See also: Emily Gore’s Scannabago concept))

Clarity

Many initiatives that garner excitement in the library community look great from the outside, but are fraught with loosely defined goals, aims, and a general lack of detailed plans for moving forward. Librarians, eager and skeptical at the same time, require a deep sense of purpose tied to real, concrete outcomes. DPLA is close to providing that level of clarity, but additional information would be helpful, such as: what methods are in place for rural libraries to begin collecting and submitting oral histories?; will there be a PBS-style curriculum module to engage school librarians?; is there a media campaign targeted at public libraries?; a toolset for scholarly utilities that could help with citing items and repurposing metadata?. These details would address Andy Woodworth’s question, “How does this apply to my patrons?” It is still a little early in the process to expect the fullness of clarity that many of us would like, but continuing to ask and expressing our detailed needs will keep practicality at the forefront of this developing initiative.

These four areas require as much from librarians as they do from those steering the Digital Public Library of America. Rather than approaching the DPLA as a Harvard initiative, I’d like to propose that we take them at their word and take ownership of this as a realistic, collaborative, inclusive, “public” opportunity to showcase one aspect of value for libraries in a digital world. Considering the practical implications of a national digital library for our daily work, we should contribute to the conversation and development of the platform, the portal and the partnerships that define the DPLA. If it is successful, DPLA could be a national treasure which brings to light the value and essential qualities of our beloved organizations, as well as the physical collections and intellectual issues that we labor on daily (copyright, fair use, information literacy, access). Even if we don’t each have the time to get personally involved, we ought to articulate the wide-ranging possibilities and benefits of such an idealistic enterprise to public schools, to higher education, and to citizenship and government. In fighting for the ideals on an ambitious project like DPLA, we are fighting for our own place in the information economy.

The Digital Public Library of America is, as Robert Darnton puts it, “the confluence of two currents that have shaped American civilization: utopianism and pragmatism” (Darnton, 2013). Let us then envision the grand ideal while rolling up our sleeves. What role could be more fitting for American librarians than a passion for principles blending with an enduring work ethic? It is who we are and what we do.

Further reading and discovery:

StackLife, Library Observatory and DPLA Map – examples of what can be built on top of the DPLA’s open API.

Now, With No Further Ado, We Present… The Digital Public Library of America! The Atlantic, 4/18/2013.

DPLA Launches to the Public. Huffington Post, 4/18/2013.

How the DPLA hopes to build a real public commons. The Verge. 4/3/2013.

What We Hope the DPLA will Become. Open Knowledge Foundation blog. 4/17/2013.

References:

Borman, Laurie. Building the Digital Public Library. American Libraries Magazine, 4/19/2012.

Cottrell, Megan. A Digital Library for Everyone. American Libraries Magazine, 4/15/2013.

Darnton, Robert. The Digital Public Library of America is Launched. The New York Review of Books. 4/25/2013.

De Rosa, Cathy, Chrystie Hill, Andy Havens, Kendra Morgan and Ricky Erway. America’s Digital Future: Advancing a Shared Strategy for Digital Public Libraries. 2011, OCLC.

Enis, Matt. Q&A: Dan Cohen on His Role as the Founding Executive Director of DPLA. The Digital Shift: Library Journal. 3/12/2013.

Heller, Margaret. Report from the Digital Public Library of America Midwest. ACRL Tech Connect. 10/22/2012

Hill, Nate. What a National Digital Library means for Public Libraries. Text of a talk given to Digital Library Federation, 2011.

Palfrey, John. What is the DPLA? Library Journal. 4/8/2013

Palfrey, John. What the DPLA can mean for Libraries. The Digital Shift: Library Journal. 1/3/2013

Raphael, Molly. The First Digital Public Library of America Workshop. Inside Scoop: American Libraries Magazine. 3/9/2012.

Rothman, David. It’s Time for a National Digital-Library System: But it can’t serve only elites. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2/24/2011

— The risks if the DPLA won’t create a full-strength national digital library system: Setbacks for K-12, family literacy, local libraries, preservation, digital divide efforts? LLRX.com. 12/19/2012

Vandegrift, Micah. The Digital Public Library of America. Hack Library School. 5/10/2011.

***Thanks, as always, to Lead Pipe colleagues Emily, Ellie, Erin, and Brett for editing and challenging my writing and ideas herein. A special thanks to Emily Lloyd of Hennepin County Libraries for serving as an external reviewer.

Pingback : The Scoop on the DPLA | LIS 670 Student Discussion Blog

Pingback : The Digital Public Library of America | Exploring Social Informatics

Pingback : DPLA for you & me | your libarchivist

Pingback : Call for Endowment Seeks to Ease the Suffering of Libraries