The Digital Opaque: Refusing the Biomedical Object

In Brief

This essay examines the extractive practices employed in biomedical research to reconsider how librarians, archivists, and knowledge professionals engage with the unethical materials found in their collections. We anchor this work in refusal—a practice upheld by Indigenous researchers that denies or limits scholarly access to personal, communal or sacred knowledges. We refuse to see human remains in the biomedical archive as research objects. Presenting refusal as an ethical and methodological intervention that responds to the often stolen biomatter and biometrics in medical collections, this essay creates frameworks for scholars working with archival or historical materials that were obtained through violent, deceitful, or otherwise unethical means.

By Sean Purcell, Kalani Craig, and Michelle Dalmau

Introduction

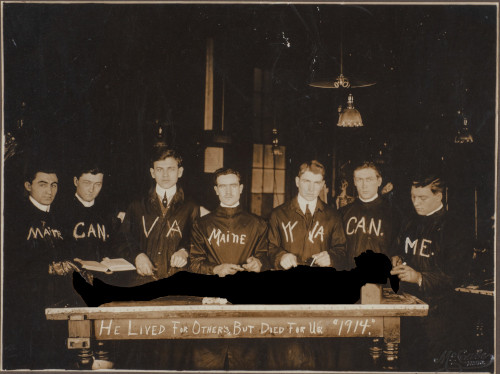

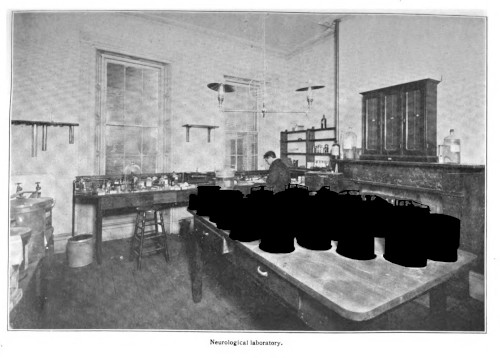

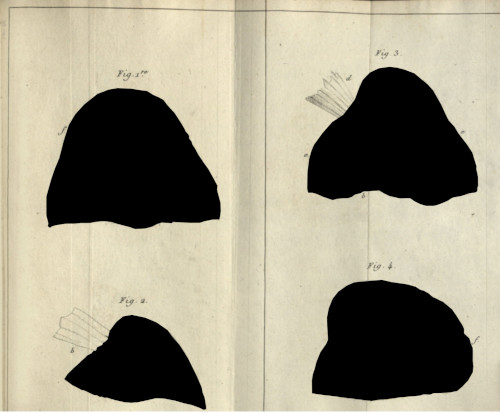

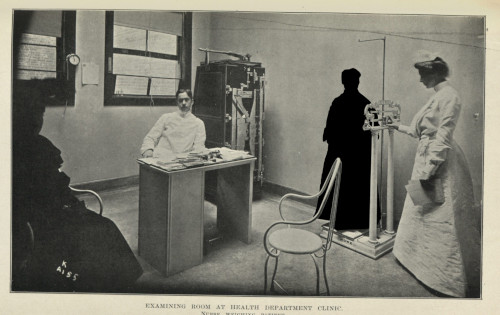

There are many photographs of doctors at the turn of the twentieth century posing with dead human subjects. Medicine’s visual culture in this period is marked by a nonchalance toward the deceased subjects who constituted their research materials. Medical students posed with their anatomical cadavers (Warner 2014) (fig. 1), and doctors were framed in candid shots in ways that displayed their wet specimens (fig. 2). John Harley Warner, writing of anatomical students’ group photographs, noted how, for American doctors who often acquired their cadavers from Black graveyards, these photographs mimicked the composition of the lynching photograph:

The practices represented in photographs of this other “strange fruit” involved not just dismemberment of dead bodies but also constant threat to certain black communities of postmortem violation, actual trauma inflicted on those still living. (16)

Because these human remains were obtained prior to the codification of informed consent (Lederer 1995), and because medical science historically depended on theft as a means to forward epistemic, cultural, and monetary value (Richardson 1987; Sappol 2002; Redman 2016; Alberti 2011), there remains an open wound caused by the use of stolen human material in the creation of biomedical argument.

This essay describes ethical and methodological interventions developed in response to the extractivist program employed by medical scientists at the turn of the twentieth century. Our intervention, the Opaque Publisher (OP), introduces a theoretical framework that lets professionals whose work engages with stolen material choose which sections of material in their collections need to be redacted. The framework also provides readers a way to engage with these ethical decisions through a toggling interface (fig. 3). This essay is the first of two essays written for Lead Pipe on the ways digital methods afford different approaches to ethical problems. In our second essay we will go into more detail on the design-based methodology that led the development of the OP, as well as DigitalArc, the community archiving platform from which the OP was originally built.

We ground our argument in a case study: a dissertation that examines biomedical extractivism in tuberculosis research at the turn of the twentieth century (Purcell 2025). Tuberculosis has been the center of exclusionary and anti-immigrant policies employed by nations, states, and cities. These policies tend to target brown and black populations, creating an apparatus to more easily deny immigration from those communities (Abel 2007). The disease has also been flagged to leverage eugenicist discourses in the United States (Feldberg 1995), and has been used to manufacture middle and upper class aesthetics of health and wellness (Bryder 1988). The dissertation makes a strong case study for our digital-methods intervention because it examines how biomedical and public health professionals studied the disease, and how these research programs fit into America’s expanding biomedical and public health infrastructures.

The process of medical research, especially the research employed by medical scientists at the turn of the twentieth century, sees research subjects as valuable epistemic resources. We use the term ‘epistemic’ to refer to the philosophical tradition of epistemology—or the study of how knowledge is created—with a particular stress on implicit historical, cultural, and ideological assumptions that Michel Foucault frames in the discursive épistémè (Foucault 1994). Building on histories of anatomy that describe the commodification and exploitation of postmortem subjects, we argue that biomedical science depends on the theft of human material. These extractive methods were built out of historical practices that disregarded the autonomy of non-white communities, seeing their lives, cultures, and histories as a resource to be mined (Redman 2016; Washington 2006; Sappol 2002).

Megan Rosenbloom, in her excellent book on anthropodermic bibliopegy—or books bound in human skin—describes the problem we address in an anecdote about a book challenge brought against Édouard Pernkoft’s Topographische Anatomie des Menschen. The book was written by a Nazi scientist with illustrations that may have been drawn using the bodies of subjects killed by the Nazi regime. Describing USC’s Norris Medical Library’s decision to keep the book, while adding additional information about the history of the text, Rosenbloom writes, “if books have to be removed from a medical library because the bodies depicted in them were obtained through unethical and nonconsensual means, there might not be an anatomical text left on the shelf” (170). Central to Rosenbloom’s logic is a presumption that knowledge–medical, historical, cultural knowledge–supercedes the needs of abused historical subjects, their communities, and their descendants.

Rosenbloom’s careful attention to historical violences in the history of medicine describes a broader problem practiced by knowledge workers in medical libraries, archives, and museums. Knowledge workers are obligated to maintain and preserve these materials because of their epistemic and cultural value, in spite of their awful, nonconsensual origins. We wanted to create an ethical and methodological framework that enabled the divestment of stolen human biomatter and biometrics from institutions, whose collecting histories harmed Black, brown, and Indigenous communities (Monteiro 2023). Knowing that the majority of these research materials—subjects depicted in medical atlases, described in research reports, and whose remains have been collected and maintained in medical museums—were extracted from people who never consented to that research, we present a model that calls attention to that theft. We ask, is it possible to do research in the history of medicine that respects our interlocutors’ autonomy?

Our answer to this question is a methodological one: we argue for librarians, archivists, and knowledge workers to refuse the object. While biomedical researchers saw the materials that populated their journals, textbooks, and archives as objects, we advocate for an approach that reestablishes the human base upon which these disciplines are built. Refusing the object is a countermethod to the reductive, dehistoricizing, and decontextualizing processes that harm humans caught in biomedicine’s dragnet (Tuck & Yang 2014, 814).

This approach builds on frameworks around refusal. Refusal is a practice described and employed by Indigenous researchers and academics working with Indigenous communities that denies academic access to personal, communal, and sacred knowledges (Simpson 2007; Tuck & Yang 2014; Liborion 2021). In its most broad definition, refusal is a generative, socially embedded practice of saying ‘no’, akin to, but distinct from, resistance. It is a critique that is levied in different ways by different actors, circumscribed by their social and political context (McGranahan 2016). In its original contexts, refusal refers to the gestures made by research subjects to disrupt and disallow research (Liboiron 2021, 143). We argue that knowledge workers have ethical obligations to their interlocutors that require unique, case-by-case interventions (Caswell & Cifor 2016), and that sometimes these obligations force us, as Audra Simpson argues, to work through a calculus of “what you need to know and what I refuse to write in” (2007, 72). We argue for frameworks that enable knowledge workers to refuse materials that depend on the objectification of, and through that objectification the commodification of, human subjects.

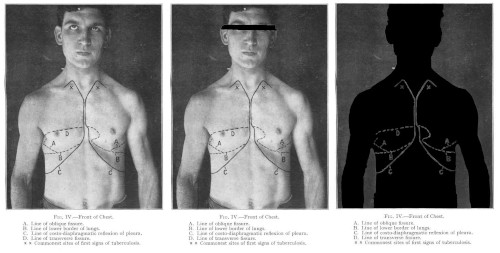

Building from arts-based approaches to opacity (Blas 2014; Purcell 2022), we developed protocols—structured methods applied uniformly across our primary materials—for refusing the objectifying practices employed in the creation of our primary sources. These protocols highlighted the ways opacity would be scaffolded in a final published work, imagining how norms of anonymity and consent might be applied post hoc. For text, we redacted words where our primary sources revealed too much about their subjects (fig. 3). For images, we erased parts of people’s bodies depending on who was in the frame (fig. 4). What drove our design was a desire to scaffold the effects of refusal in ways that were obvious and intentional. We wanted to show the effects of refusal, rather than hypothesize about what might be lost in the process.

For this essay, we will begin with a discussion of objectifying practices in biomedical epistemics, before talking through refusal-as-method. We will finish with a discussion of ethics audits, which can be applied late in a research project using the concepts we have outlined in this article.

Pathology’s Objects

One of the messier epistemic contradictions which enables the collection of biomatter, biometrics, images, and histories from patients is that the process of collection transforms the patient or subject into an object. Object, as we use the term, refers to a representation of phenomena used in scientific research that has been divorced from its historical, cultural origin (Daston & Galison 2007, 17). Biomedical research depends on multiple objectifying practices, the most famous of which is known as the clinical gaze. As described by Michel Foucault in The Birth of the Clinic, this visual practice refers to the ways doctors are trained to see the difference between a patient’s body and an assumed ‘normal’ human anatomy as disease. The first issue with this visual practice is that it imagines a single supposedly perfect human anatomy (a body of a cis, heterosexual, white, nondisabled man), and that this model assumes that anyone whose body is different from this constructed normal (in sexuality, gender, race, or ability) as being diseased.

The second issue with the practice comes from the clinical method. This method ties case histories with postmortem examination: patients would visit a clinic, doctors would track their symptoms, collect relevant information—their family histories, the progression of the disease—and then, if the patient died under their care, doctors would try to link the patient’s symptoms to phenomena found at autopsy. A good example of this practice can be seen in the work of René Laennec, a French doctor who practiced clinical research in the post-revolutionary period (Foucault 1994, 135-36). Laennec observed tubercles—hard, millet sized growths—in the lungs of the consumptive patients he autopsied, and he connected the symptoms experienced by these patients to these pathologies (fig. 5).

The clinical gaze has long been described as one that alienates patients because doctors are only trained to see them as nests of symptoms. What is important to remember is that the clinical method, as it is described by Foucault, is similarly alienating, insomuch as it sees patient symptoms as data to be gathered, analyzed, and extrapolated for medical progress. Even case histories, filled as they are with intimate details of an individual’s life, are described in such a way as to flatten that life into possible causes that may be examined in the abstract for future biomedical argument.

What Foucault neglects to mention, but which anatomical historians have made clear, is that developing in the same period was a commodification of human remains in medical contexts. Ruth Richardson has linked the popularization of the Parisian anatomical method, which required medical students to anatomize a cadaver in their training, to the rise of graverobbing in England and Scotland in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In the same period, medical schools were deemed more or less prestigious based on the scale and quality of their medical museums and specimen collections (Alberti 2011). The production of a valuable, commodifiable object went hand-in-hand with the epistemic framework that dehumanized patients in diagnosis. The creation of a pathological specimen—a representational object that purports to show some aspect of a disease’s progression—splits the disease from the human subject whose life, death, and afterlife was necessary in the collection of that phenomenon. In denying this connection, biomedical argument enables a specimen to stand-in as an objective representation for observation and study.

This objectification extends beyond medical contexts. The problem that arises is that to engage with these historical materials as academics, even as practitioners of subjective, qualitative research, we have to approach them as research objects—as representational materials that describe the phenomena we critique. To refuse the object in the history of medicine is to refuse to decouple the biomedical object from the subject from whose body this specimen was taken. It is a refusal and denial of the material’s ultimate epistemic value, both for the sciences but also for humanistic, historical, or qualitative research.

Opaque Protocols

Our methods to refuse the objectifying practices in medicine began with a speculative approach to the history of medicine. We use “speculative” to refer to the methodological interventions into archival research argued for by Saidiya Hartman. These methods ask for historians to read against the grain of the archive, and to see the archival omissions as being part and parcel of broader carceral, colonial histories (2008). Krista Thompson has built on this scholarship to advocate for “speculative art history” which practices historical fabulation—the manipulation of archival materials—to imagine histories that otherwise would never be seen (Thompson 2017; Lafont et al. 2017).

The speculative historical method enables us to intervene on primary materials in critical, reparative ways. It allows us to shift our understanding of the primary document as a concrete, essential thing, to something that comes from structural practices that denied the humanity of certain subjects. By applying opacity—these methods of conspicuous, obdurate erasure—to primary sources, we reassert the centrality of the patient in our argument (fig. 4). This term, opacity, derives from Édouard Glissant’s critique of western academic essentialism. To be opaque is to refuse access to a phenomena’s root and the totalitarian possibility afforded by control of that essential character (1997, 11-22; 189-94).

We extend this practice beyond the platform—using this method in the images we have supplied for this article—as a way to continue the same critique: Were these images necessary for our argument? Are our claims lessened if they are intentionally marked or changed?

Refusing the Object

Our approach to opacity came about from a nagging discomfort we experienced when engaging with materials in the history of medicine. So much of medicine’s violence has been practiced in the open (Washington 2006, 12), and its harms are felt as a “bruise” by the communities whose bodies were subjected to research and ignored by the institutions that benefited from those practices (Richardson 1987, xvi). Taking primary evidence at face value, accepting the harms, and deeming them necessary for revelatory research felt hypocritical, especially because academic research so often only benefits those doing the research and not their subjects (Hale 2006).

The opaque protocols we used to redact images and text (figs. 3, 4, 6 show multiple layers of opacity) were also moments of refusal—of denying the reader access to stolen, coerced, and unethically extracted materials produced in biomedical research. Where refusal is a mode adopted by research interlocutors (Liborion 2021, 143), it is also a tool for knowledge workers working in obligation to the people and communities who inform their research (Simpson 2007). For Max Liboiron, in the context of community peer review, refusal “refers to ethical and methodological considerations about how and whether findings should be shared with and within academia at all” (2021, 142). Premised on this idea is the realization that not all knowledge needs to be known within academic systems. As Liboiron writes, “[g]iving up the entitlement and perceived right to data is a central—the central!—ethic of anticolonial sciences” (Ibid., 142, footnote 96).

Refusal, for us, is predicated on an understanding that our current knowledge infrastructure depends on extraction enacted through theft and hidden in plain sight. Roopika Risam, in her keynote for DH2025, notes the digital humanities’ long quest to make collections accessible has its own ideological basis. She writes,

Because access without accountability risks becoming a kind of digital settler colonialism: where archives are opened but not contextualized, where stories are extracted from communities but not returned to them, where knowledge circulates but the people who shaped it are left behind. It is access that takes, not access that gives back. (2025)

There is a broader need to acknowledge that the materials we maintain, use, and reproduce are so defined by their extraction—thefts of people’s biomatter, their history, and their secrets. Refusal is to say ‘no’ to this extraction, and to critique why we reveal materials in such ways.

Knowing that biomedical materials are linked to human subjects with cultures and histories, we need to acknowledge that in order to respect a community or patient’s consent we may have to lose those materials. We refuse the processes that turn people into objects. We refuse to place the value these materials offer our institutions and disciplines above the people whose bodies were made into valuable epistemic resources.

Ethics Audits

The application of opacities—obvious redactions of text and images—to the dissertation, The Tuberculosis Specimen, occurred at the end of the research and writing process. It was only after each chapter had been approved by the dissertation chair that images and text would be made opaque. Every image had to be reviewed for content, and if an image included sensitive material—human subjects undergoing treatment, children who could not have consented to having their image taken, or human remains—it would need to be edited multiple times for the final published website (figs. 4, 6, 7 illustrate this editing process). Primary quotations were also reviewed for sensitive materials. For the final publication, the text that was deemed unethical, and which needed opacity applied, was changed in the final markdown (.md) file uploaded to the site. Span classes, or hypertext markup language (HTML) wrappers that flag certain stylistic or functional changes on the final site, were added to the text to enable the redaction of that text.

The original goal was never to actually erase the materials. Many of the images that were used in that project, and which we shared in this essay, were obtained through HathiTrust—a digital library made up of many university collections which are, and will remain, available for academic research. The speculative turn was a means of thinking through the argumentative need for such materials. It helped us reconsider our roles as scholars and stewards, digital humanists and critical practitioners.

In preparing the dissertation to be published using the OP, there emerged two parallel reflective practices: both the text and image had to be made opaque. This process required a great deal of labor, editing multiple versions of each image (fig. 7). This labor was a boon insomuch as it afforded time and effort to think through each image: What is being shown? Who is central in the image? Who has agency and who does not? What needs to be erased? And what needs to be maintained (fig. 7)?

The process of digitally editing these photos, of cutting away bodies with the help of image editing tools, was also a process of touching upon them, enabling a haptic relationship between ourselves and the primary source. As Tina Campt argues, holding archival materials, grasping them in our hands, forces us “to attend to the quiet frequencies of austere images that reverberate between images, statistical data, and state practices of social regulation” (90). The process of making images and text opaque was a laborious one, not a rote one like cropping an image or changing a .tiff into a .jpg. It was a moment of reflection and communion. It let us touch upon the lives of our interlocutors, to say: I see you. You did not want to be here.

This work enabled us to better understand the practices that captured subjects within academic research. Our conclusions regarding the continuity between subject and object, between patient and stolen remains, are the result of this hands-on process.

From this experience, we advocate for the use of a research audit. This is a moment of retrospective reflection that occurs at the end of a research program but before publication. During a research audit, a researcher or team of researchers review their work. They conduct a close reading of their evidentiary materials with the goal to tease apart the epistemic assumptions in their research that reduce, dehumanize, or alienate their human interlocutors. In this phase of the work, researchers ask, whose lives, deaths, and afterlives are integral to my research? Why am I using them? And who benefits from this work? Am I working in obligation with those who make my own research possible?

Obligation, as we use it, is indebted to Indigenous axiology, epistemology, ontology, and methodology (Wilson 2008), particularly to the kind of relationships between researchers and subjects. Kim TallBear, describing these relationships, reminds us that we are obligated to care for everyone who our research touches upon, both those from subaltern groups and as well as those from powerful positionalities (2014). Our research is not our own, but a collaboration that ties us to the people, institutions, histories, and moments that inform our arguments.

This end-of-project reflection helps us attend to everyone who is entangled in our research. Importantly, it occurs after completing research, and it is intentionally separate from the requirements of institutional review board (IRB) approval. In an ethics audit, researchers review their work, and mark the finished product in ways that show their fraught relationship between their jobs as knowledge workers and their obligations to their interlocutors. The opacity protocols developed for the OP and The Tuberculosis Specimen were a means of showing that the evidentiary requirements for a completed dissertation conflicted with an ethics of care. They were designed to make clear to the reader that 1) as scholars we have to show our work, and 2) this practice of showing is often at the expense of those whose lives and deaths are entangled in our research programs.

The ethics audit is a moment to embrace hypocrisy as a critical method, acknowledging that knowledge work is always partial, contested, and conflicted. This idea is built out of the feminist, anticolonial approach to ethics described by Max Liboiron and their colleagues. Seeing a need to navigate the complex, impossible, overlapping, and contradicting ethical demands in a research project, they write,

our obligations and relations are often compromised, meaning we are beholden to some over others, and reproduce problematic parts of dominant frameworks while reproducing good relations at other scales. Compromise is not a mistake or a failure—it is the condition for action in a diverse field of relations. (137-38)

The opaque methodology we described above was premised on an assumption that we cannot do ethically perfect research. We instead chose to do the best research we could, while considering the historical, cultural, and epistemic violence that we addressed and within which we are enmeshed (Caswell & Cifor 2016). We inhabit a hypocritical position by design, revealing and concealing in the same breath.

Conclusion

This intervention was developed to advocate for the return of stolen materials in the history of medicine. In working on this project, we found ourselves in a double bind: we have built an environment for more and new scholarship, and find ourselves arguing against that kind of output. Caring for the lives, deaths, and afterlives of research subjects means not using their bodies, histories, and images to further our own agenda, and yet, in this essay, we have. We wanted to show our work, and to convey the importance of these problems, but realize that our evidence is, itself, the problem.

Refusal, in academic contexts, is multi-leveled in practice. Our interlocutors and subjects can refuse us. We knowledge workers can also refuse (Simpson 2007; Liboiron 2021). Academic refusal does not have a one size fits all model. It is an imperfect patchwork assembled through care, attention, and practice. The approach to opacity outlined in this essay is flawed by design. We write from institutions with their own histories of collection and exploitation.

Modes and methods of refusal do not have to be clean, or perfect, nor do they foreclose the creation of knowledge. To that end, we developed the OP as a platform that refuses and reveals, in an attempt to make these contradictions more visible. The process forced us, as knowledge workers, to more carefully assess our materials, and to work in obligation to the people whose lives, deaths, cultures, and histories are necessary to making our arguments.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Emily Clark, Vanessa Elias, and all of our colleagues at the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities at Indiana University Bloomington for their help at different times during the research process. We are also thankful to Marisa Hicks-Alcaraz who assisted in the early phases of our research. This article was vastly improved through a generous and generative open-peer review process. Thanks to Roopika Risam, Jessica Schomberg and Pamella Lach for their constructive feedback. This research was made possible thanks to funding from the New York Academy of Medicine, the Center for Research on Race Ethnicity and Society, and with support from the American Council of Learned Societies’ (ACLS) Digital Justice grant program.

This essay is the first in a two-part series of articles developed for Lead Pipe. Where this essay focuses on the theoretical grounding of our critique, our follow-up essay will describe and detail the specific technological and methodological approaches we developed while creating the Opaque Publisher (OP) and DigitalArc. Together these essays will show how ethical frameworks and methodologies can be produced through a design-based approach to research.

Editor’s note: At the authors’ request, this article was modified post-publication to add a missing citation.

References

Abel, Emily K. 2007. Tuberculosis & the Politics of Exclusion: A History of Public Health & Migration to Los Angeles. Rutgers University Press.

Alberti, Samuel J. M. M. 2011. Morbid Curiosities: Medical Museums in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Oxford University Press.

Blas, Zach. 2014. “Informatic Opacity.” Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, no. 9.

Bryder, Linda. 1988. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. Clarendon Press.

Campt, Tina M. 2017. Listening to Images. Duke University Press.

Caswell, Michelle, and Marika Cifor. 2016. “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives.” Archivaria 81: 23–43.

Daston, Lorraine, and Peter Galison. 2007. Objectivity. Zone Books.

Feldberg, Georgina D. 1995. Disease and Class: Tuberculosis and the Shaping of Modern North American Society. Rutgers University Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1994a. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. Vintage Books.

Foucault, Michel. 1994b. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Vintage Books.

Glissant, Édouard. 1997. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. University of Michigan Press.

Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12 (2): 1–14.

Lederer, Susan. 1995. Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Liboiron, Max. 2021. Pollution Is Colonialism. Duke University Press.

Liboiron, Max, Emily Simmonds, Edward Allen, et al. 2021. “Doing Ethics with Cod.” In Making & Doing: Activating STS through Knowledge Expression and Travel, edited by Gary Lee Downey and Teun Zuiderent-Jerak. The MIT Press.

McGranahan, Carole. 2016. “Theorizing Refusal: An Introduction.” Cultural Anthropology 31 (3): 319–25.

Monteiro, Lyra. 2023. “Open Access Violence: Legacies of White Supremacist Data Making at the Penn Museum, from the Morton Cranial Collection to the MOVE Remains.” International Journal of Cultural Property 30: 105–37.

Purcell, Sean. 2022. “Dermographic Opacities.” Epoiesen, ahead of print. http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2022.1.

Purcell, Sean. 2025. “The Tuberculosis Specimen: The Dying Body and Its Use in the War Against the ‘Great White Plague.’” Indiana University. tuberculosisspecimen.github.io/diss.

Redman, Samuel J. 2016. Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Harvard University Press.

Richardson, Ruth. 1987. Death, Dissection and the Destitute. The University of Chicago Press.

Risam, Roopika. 2025. “DH2025 Keynote – Digital Humanities for a World Unmade.” DH2025, Lisbon, July 18. https://roopikarisam.com/talks-cat/dh2025-keynote-digital-humanities-for-a-world-unmade/.

Rosenbloom, Megan. 2020. Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Sappol, Michael. 2002. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton University Press.

Simpson, Audra. 2007. “On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship.” Junctures 9: 67–80.

Sutton, Jazma, and Kalani Craig. 2022. “Reaping the Harvest: Descendant Archival Practice to Foster Sustainable Digital Archives for Rural Black Women.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 16 (3).

TallBear, Kim. 2014. “Standing With and Speaking as Faith: A Feminist-Indigenous Approach to Inquiry.” Journal of Research Practice 10 (2).

Thompson, Krista. 2017. “Art, Fiction, History.” Perspectives.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2014. “Unbecoming Claims: Pedagogies of Refusal in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 20 (6): 811–18.

Warner, John Harley. 2014. “The Aesthetic Grounding Of Modern Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 88 (1): 1–47.

Washington, Harriet A. 2006. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Harlem Moon & Broadway Books.

Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing.