What Is Digital Humanities and What’s it Doing in the Library?

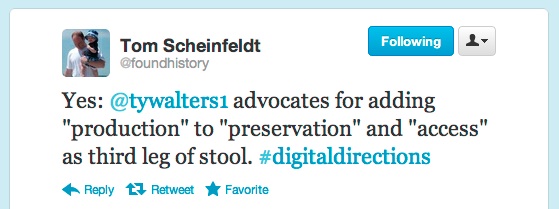

tl;dr – Libraries and digital humanities have the same goals. Stop asking if the library has a role, or what it is, and start getting involved in digital projects that are already happening. Advocate for new expanded roles and responsibilities to be able to do this. Become producers/creators in collaboration with scholars rather than servants to them.

Introduction – On Kirschenbaum

In the spring of 2011, Matthew Kirschenbaum, Professor of English at the University of Maryland, published a piece for the Association of Departments of English titled “What Is Digital Humanities and What’s it Doing in English Departments?” That piece has become one of the central defining works for the field/movement/ideal of Digital Humanities (DH), along with several other key articles (see Sources for Further Reading section at the end of the article). Kirschenbaum’s thesis is that over time “digital humanities has accumulated a robust professional apparatus that is probably more rooted in English than any other departmental home.” Definitive as that is, with ample proof for the claim, he leaves room for an expansion and ends the article writing that:

…digital humanities today is about a scholarship (and a pedagogy) that is publicly visible in ways to which we are generally unaccustomed, a scholarship and pedagogy that are bound up with infrastructure in ways that are deeper and more explicit than we are generally accustomed to, a scholarship and pedagogy that are collaborative and depend on networks of people and that live an active 24/7 life online. ((Kirschenbaum, Matthew. (2010). What is Digital Humanities and what’s it doing in English Departments? ADE Bulletin, 150. Pg. 60. Accessible at http://mkirschenbaum.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/ade-final.pdf ))

Aside from the complications of defining what is/are/is-not digital humanities, it is in this publicly visible, collaborative, online network and infrastructure that the Library should begin to see itself.

In light of articles such as Kirschenbaum’s, libraries have struggled to define their role in digital humanities, as the discussions around DH often resort to theoretical discourse or technical know-how. Arguably, however, because the library already functions as a interdisciplinary agent in the university, it is the central place where DH work can, should be and is being done. DH projects involve archival collections, copyright/fair use questions, information organization, emerging technologies and progressive ideas about the role of text(s) in society, all potential areas of expertise within the field of librarianship. In fact, three out of four highly active digital humanities centers are physically located with their respective University libraries; Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH) at the University of Maryland – College Park, ScholarsLab at the University of Virginia, and Digital Scholarship Commons (DiSC) at Emory University are all housed in the library. The Center for History and New Media (CHNM) at George Mason University is affiliated with the History and Art History Department but is located in its own space. Comparatively, and illustrative of the ongoing Hack vs. Yack dichotomy in DH (doing and making things rather than critically analyzing them), academic departments are more often where digital humanities is discussed, theorized and written about.

Additionally, the “Alt–Ac” (alternative academic) workforce, defined as people with graduate training in the humanities who pursue careers off the tenure track, tend to aim their professional aspirations toward working in a library, often without a traditional training in librarianship. The CLIR Fellowship program is particularly designed for this. As evidenced by the recent Alt-Ac survey, self-identifying DHers fall into a wide variety of disciplines, many hold PhD’s and few claim the title of “librarian.” Although maintaining a visibility in DH, the Library (writ large) has yet to fully understand itself as essential to the goals of digital humanities. Through a brief overview of several foundational writings on digital humanities, this article will attempt to point out some areas where the Library must better articulate this role. Also, I hope to encourage librarians who are invested and interested in this and related areas to begin to approach digital projects as opportunities for partnerships. Lastly, I will challenge the “service” model of librarianship and propose that the self-perception of the field needs to evolve to a “production” model.

What You Do with a Million Books, Screwmaneutically Speaking: The Library as Place – On Ramsay

Wayne Wiegand, historian of print culture and libraries, holds a mantra regarding the library as place. He states that rather than understanding “the user in the life of the library, we must see the library in the life of the user.” ((Wiegand, Wayne. (2005). Library As Place. Presentation to the 56th Annual Biennal Conference North Carolina Library Association. Accessible at http://www.ncl.ecu.edu/index.php/NCL/article/viewFile/70/88)) It would not be a stretch to attribute much of the innovation that libraries are undergoing to this ideal; that the user has evolved, and therefore so must the library. Library programming now includes tips on web searching, there are more computer terminals than card catalogs, and coffee is close at hand. Further, the library, as a staid institution of knowledge and exploration, should then blend in with the multitude of ways that the user discovers information. Or so the story goes. Placing Wiegand’s hopeful thesis in the context of recent proclamations about the lack of necessity of librarians and the death of the humanities, one could assume that both are shushing and critically-theorizing themselves down the drain hole, and that there is no place for the library in the life of the user. ((See also The Huffington Post’s Libraries In Crisis section – http://www.huffingtonpost.com/news/libraries-in-crisis))

The library must function as a place where scholars can try new things, explore new methodologies and generally experiment with new ways of doing scholarship, in order to challenge that perception. Stephen Ramsay, Associate Professor of English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and a Fellow at the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, in his “The Hermeneutics of Screwing Around; or What You Do with a Million Books” suggests that browsing, in opposition to searching, is a cultural imperative. Browsability, in the most traditional sense, is still a relatively sore subject in librarianship. As resources move digital, and space is reallocated from stacks to “labs” and “commons,” the argument has been that browsing is non-imperative to the mission-critical tasks of the modern library. However, as Ramsay puts it:

It’s not a matter of replacing one with the other, as any librarian will tell you. It is rather to ask whether we are ready to accept surfing and stumbling—screwing around, broadly understood—as a research methodology. For to do so would be to countenance the irrefragable complexities of what ‘no one really knows.’ Could we imagine a world in which ‘Here is an ordered list of the books you should read,’ gives way to, ‘Here is what I found. What did you find?’ ((Ramsay, Stephen. (2010). The Hermeneutics of Screwing Around. Accessible at https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=http://www.playingwithhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/hermeneutics.pdf&pli=1))

Reimagining the place of the library, then, in light of the libraries’ role in the digital humanities, is not simply as a place to get the right answers, or be directed to the correct resource. The library must facilitate the Screwmeneutical Imperative, browsability and playfulness. The reference interview, guiding a patron to a specific research question in order to provide a specific research answer, rather than offering a method of wayfinding, needs to adapt to allow for exploration, particularly in dealing with scholars and students in the humanities.

Further, the library must be willing to allow dedicated time for what happens after exploration. The “serve ‘em and send ‘em along” model is no longer serving a patronage whose information needs include planning, building and executing projects that utilize the strengths of librarianship (information organization and broad contextualization).

Reframing the library as a productive place, a creative place, producing and creating something – whether that be digital scholarly works or something else entirely – will open the door to allow the library into the life of the user. One role for the library in DH, then, is to support the journey of research as a means in itself, and encourage imaginative, new, transformative uses of the products of research. ((Also noted in the recent CLIR report “One Culture. Computationally Intensive Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences.” Brief commentary with links to the report – http://digitallibrarians.org/node/6150))

Why Digital Humanities? – On Spiro

Asking what digital humanities is or who’s allowed to be involved fails to get at the real value this field offers to academia, cultural heritage and to the public. The key is realizing the potential that arts, music, poetry and literature can have when translated to digital forms, scraped with digital tools and re-presented to readers/viewers. At its core, DH shares the most basic goal with the library – accessibility of information. The multitude of DH projects aim to take cultural materials that were previously undiscoverable digitally, the very materials humanities scholars address and utilize for their work, and connect them to a new, broad audience. Or build a tool to enable others to do exactly that. Lisa Spiro, Director of National Institute for Technology in Liberal Education (NITLE) Labs and Editor of the Digital Research Tools (DiRT) wiki, in her presentation “Why Digital Humanities?” outlines the goals of the field from her perspective, honing in on five areas where digital humanities aims beyond traditional academic scholars.

1) provide wide access to cultural information,

2) enable manipulation of that data,

3) transform scholarly communication,

4) enhance teaching and learning, and

5) make a public impact. ((Spiro, Lisa. (2011). Why Digital Humanities. Presentation accessible at http://digitalscholarship.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/dhglca-5.pdf))

Plainly, these overlap with librarianship at its best, and as the library works to refine its impact on society, exploring these areas through the lens of DH is a useful consideration.

It is no surprise that words like “manipulate,” “transform,” “enhance,” and “impact” are leveraged when discussing a digitally-focused movement. The Tech sector might use the word “disrupt.” In a good PR move, adopting trends in cultural discourse can lend credence to misunderstood areas. This bisects both DH and the library in the reality of attempting to communicate the value of the work we do as librarians and digital scholars. A recent College and Research Libraries News article, “2012 top ten trends in academic libraries,” claims that “Academic libraries must prove the value they provide to the academic enterprise… unless we give our funding bodies better and more compelling reasons to support libraries, they will be forced by economic reality to stop doing so.” ((ACRL Research and Plnaning Review Committee. (2012). 2012 top ten trends in academic libraries: A review of the trends and issues affecting academic libraries in higher education. College and Research Libraries News, June 2012 73:311-320. Accessible at http://crln.acrl.org/content/73/6/311.full)) What the digital humanities offers that libraries typically have not is a tangible product – a website, a digitized collection with a built in text-mining tool, a tool to add layers of meaning to maps, a sexy interface. Making “stuff” indicates effectively that there is work being done to provide valuable, useful, interesting content to an information-sucking world. Additionally, DH revolves around building things that allow these projects to grow, develop, adapt and entice a wide variety of users including programmers, armchair historians, high-school students, and funding bodies(!), for example. Tying the library’s strengths, people and ideals to tangible products of scholarly work (that aren’t necessarily “publications”) has the potential to bode well for the next round of legislation that claims “its all on Google anyways.”

Accessibility as an idea is not new to libraries. Approaching it as THE work we DO, rather than a service we offer, might be the disruptive extension that is necessary. Spiro, also in her presentation, points out the limitations of print, another sore subject for the library, that DH projects attempt to affect; one can’t search, hyperlink, embed or quickly and efficiently develop a conversation on/in/around print. Although this is evolving with new forms of texts, the challenges are considerable. Scholarly Communication, an emerging area of librarianship that is being actively explored in many institutions, is actually offering the library a distinct role in the dissemination of research. Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Director of Scholarly Communication for the Modern Language Association, eloquently states “Closing our work away from non-scholarly readers, and keeping our conversations private, might protect us from public criticism, but it can’t protect us from public apathy, a condition that is, in the current economy, far more dangerous.” ((Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. (2012) Giving it Away. Accessible at http://www.plannedobsolescence.net/blog/giving-it-away))

Framed this way, it appears DH and libraries are traveling on the same trajectory, from supposed obsolescence toward redefinition through digital accessibility.

Participating in, advocating for and managing tools around emerging models of scholarly communication is another opportunity for the library to define its place in the scope of digital humanities. Open access (scholarly communication) is to DH as open access (information accessibility) is to the library – the goal and context through which we define and promote our value.

#alt-LIS, Skunks, Hybrarians and “strange institutions” – On Nowviskie

Embracing ‘screwing around’ and intimating a stronger sense of how to DO digital accessibility are both well and good. Revolutionizing the ways in which librarians understand themselves and their work, however, is the primary task at hand. Altering the organization of the institution, doing away with reference desks, introducing new media, and all other growing pains libraries endure are ill-informed developments if the librarians, paraprofessionals and support staff have not re-imagined themselves and their skill-sets. Digital humanities, already redefining the humanities and scholars therein as per Kirschenbaum’s aforementioned piece, offers a looking glass through which to step. The shift toward alternative appointments in libraries (#alt–LIS = scholarly communications, digital humanities librarians, data librarianship, E-Science, digital archivists, project-based appointments, etc.) is building the capacity for the library to be productively integrated in digital scholarship.

Bethany Nowviskie, Director of Digital Research & Scholarship at the University of Virginia Library, is an advocate for this great migration away from traditionally-understood librarian roles. Several articles available on her blog, “Fight Club Soap,” “Lazy Consensus,” and “A Skunk in the Library,” challenge the concept that a good librarian is a servant to the academic community, sitting in wait to provide for whatever the need may be. She writes, plainly and boldly:

…[There is] a fundamental misunderstanding that librarians make in our dealing with faculty – and it comes down to what is, honestly, one of the most lovely qualities of library culture: its service ethic… The impulse is to provide a level of self-effacing service – quiet and efficient perfection – with a goal of not distracting the researcher from his work. You start this with the best of intentions, but it can lead to an ad-hoc strategy, in good times and bad, of laying a smooth, professional veneer over increasingly decrepit and under-funded infrastructure – effectively, of hiding the messy innards of the library from your faculty, the very people who would be your strongest allies if the building weren’t a black box. ((Nowviskie, Bethany. (2011). A skunk in the library. Accessible at http://nowviskie.org/2011/a-skunk-in-the-library))

The level of anxiety these kinds of statements produce in librarians is scary. However, approaching a new frame of mind as an opportunity rather than a death sentence would seem to be the more productive response. Accepting the responsibility to (quickly) adapt and evolve may incite a greater enthusiasm for the library among patrons, and propel its changing role in scholarly processes.

At the July 2011 meeting of the Scholarly Communications Institute, of which Nowviskie is a Co-Director, Shana Kimball, Head of Publishing Services, Outreach & Strategic Development for MPublishing at University of Michigan Libraries, proposed the idea that what is necessary are more “strange institutions,” blending libraries, research centers, publishing houses and technology-producers. ((Views Onto The Future. Collaborative document produced at the 2011 Scholarly Communications Institute. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1NiQSR-e-Yu88-IsVmezcE1QHPBKRNmbXpScdMhBmzC8/edit?hl=en_US)) These peculiarities, she goes on to comment, would require a workforce of “Scholar Programmers,” elsewhere called “scholar technologists,” or in the context of the library, hybrarians. More often than not, this new breed of worker is not-necessarily an MLIS holder, to the chagrin and horror of library-land. However, DH, and those invested in its future, are seeking these skill-sets, again providing an open door for librarians to revamp their self-perception and thus their perceptibility. Echoing Nowviskie’s Fight Club reference, and as a challenge to librarians, “You decide your own level of involvement.”

In closing, several points remain. This has all been said before. ((See: JISC: Does the library have a role to play in the digital humanities?, Jennifer Vinopal’s Why understanding Digital Humanities is key for libraries, Digital Humanities: Roles for Libraries by Hitoshi Kamada, Roles of librarians in digital humanities centers from the Digital Libraries Initiative 2010 meeting.)) There are already advocates inside and outside the library for deep collaboration on projects that fit into the DH mold. What, then, is digital humanities and what’s it doing in the library? In every real sense, the library always/already has the necessary pieces in place to support, engage in and do digital humanities work. The issue, in my opinion, is simply this: Digital Humanities doesn’t have a place in the library. Digital humanists do.

“Librarians” working in and across digital areas, who have been called many things over time, need to proudly identify themselves as DHers, and fully expect to be regarded as such by peers, colleagues, faculty and administrators, and let the broad work they do engage with that community.

The problem is not browsing or access, it is timidity. And until librarianship moves away from our academic inferiority complex, and embraces the calling of digital work in contrast to the vocation of servitude, digital humanities will continue to be led by smart, capable, progressive faculty members in English and History. Quoting Ramsay again, in order for the library to DO digital humanities it must embrace the charge to become “a bunch of people who had found each other through various means and who were committed to the bold and revolutionary project of talking to one another about their common interests” ((Ramsay, Stephen. (2012). Centers Are People. accessible at http://lenz.unl.edu/papers/2012/04/25/centers-are-people.html))… outside the four walls of the library.

——————————————————————–

Thank you to Lead Piper Erin Dorney, and colleagues Markus Wust at North Carolina State and Annie Pho of Hack Library School for reviewing this article, forcing clarification of my ideas, and generally encouraging this piece to the state you see it in today. Also, thanks to all those cited herein and the larger DH community for being supportive of me in my exploration of this exciting area.

——————————————————————–

Opportunities to get involved:

THATCamp – The Humanities and Technology Camp is an unconference bringing together scholars, technologists, librarians of all types, journalists, students and more. It has become the quintessential digital humanities gathering. Librarians especially should consider attending THATCamp Libraries and Digital Humanities this year and THATCamp ACRL next year.

*UPDATED* Digital Humanities Summer/Winter Institute – provides an opportunity for scholars to learn new skills relevant to digital scholarship and mingle with like-minded colleagues through coursework, social events, and lectures during an intensive, week-long event. It is “an event that combines the best aspects of a skills workshop, international conference, and summer camp.”

ACRL Digital Humanities Discussion Group – A recently formed venue for ACRL members to meet and share ideas related to Digital Humanities and the role of librarians in this emerging discipline. Also, read Bob Kosovsky’s report from this group that met for the first time at ALA annual a few days ago.

Zotero Digital Humanities Group – A place for all of those interested in how digital media and technology are changing the humanities to discuss and create the future together. Contribute items to this open bibliography.

DHAnswers – a community-based Q&A board for all things DH

DHCommons – a hub for people and organizations to find projects to work with, and for projects to find collaborators.

DiRT Wiki – a directory of tools, services, and collections that can facilitate digital research. Developing a familiarity with these tools is one way to facilitate the librarian’s role in doing the work of digital humanities.

Sources for further reading:

**Nowviskie, Bethany. “Reality Bytes.”** Text based on talk given as opening plenary of the 53rd RBMS pre-conference. http://nowviskie.org/2012/reality-bytes/ — *A must-read*

Digital Humanities and the Library: A Bibliography. http://miriamposner.com/blog/?page_id=1033

The Journal of Digital Humanities. http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/

The CUNY Digital Humanites Resource Guide – http://commons.gc.cuny.edu/wiki/index.php/The_CUNY_Digital_Humanities_Resource_Guide

Digital Humanities Now – showcases the scholarship and news of interest to the digital humanities community, through a process of aggregation, discovery, curation, and review. http://digitalhumanitiesnow.org/

Hacking The Academy – a book crowdsourced in one week. http://hackingtheacademy.org/libraries/

Humanities 2.0. Series of articles on DH in the New York Times. http://topics.nytimes.com/top/features/books/series/humanities_20/index.html

A Companion to Digital Humanities, ed. Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, John Unsworth. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/companion/

Digital Humanities Across Galleries, Archives, Libraries and Museums. A Delicious stack curated by Neal Stimler, Associate Coordinator of Images at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. http://www.delicious.com/stacks/view/KPZ9dg

McCarty, Willard. What is Humanities Computing? Toward a Definition of the Field. http://www.cch.kcl.ac.uk/legacy/staff/wlm/essays/what/

Nowviskie, Bethany. “#alt-ac: Alternative Academic Careers for Humanities Scholars.” http://nowviskie.org/2010/alt-ac/

Scheinfeldt, Tom. “ Nobody Cares About the Library: How Digital Technology Makes the Library Invisible (and Visible) to Scholars.” http://www.foundhistory.org/2012/02/22/nobody-cares-about-the-library-how-digital-technology-makes-the-library-invisible-and-visible-to-scholars/

Svensson, Patrick. “Humanities Computing as Digital Humanities.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, 9(9)3. http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/3/000065/000065.html

Thank you. This article explained some things that I’ve been experiencing, but unable to clearly articulate. I’m a librarian who teaches and partners in a wonderful undergraduate digital humanities program (WSU Vancouver’s CMDC: http://dtc-wsuv.org/cmdc/) I’ve found a home with these action-research scholars that connects my library values with their DH values in a productive and energizing manner.

There are many ways to get involved, but I would also like to mention the Digital Humanities Summer Institute (http://dhsi.org/) as a way to get involved. The DHSI is a mashup of a traditional academic conference with papers presented and a week-long intensive training workshop where scholars get to work hands-on with DH tools and techniques. This would be a good opportunity for librarians to meet the community and learn something about TEI, GIS, mobile apps, and more.

Nicholas, thanks for reading. I think there is a lot of potential for involving undergrads in dh work, and am excited to see what comes out of CMDC.

And yes, thanks for recommending the DHSI – I’ll add that to the post. Also, we should mention that MITH will be hosting the 1st DHWI (Winter Institute) in Maryland this coming January. http://mith.umd.edu/dhwi/

Micah, BRAVO! I was very much anticipating this article and it was well worth the wait. I think the reason, as a librarian, I feel disconnected from DH work is because I’m not sure how DH work orients the library “user.” I absolutely understand how this work benefits the library as a whole and the scholarly community, but am still struggling with how to make this work relevant and exciting for students. Far, far too often, students don’t want browsability or the manipulatability (I made those words up), they just want to find their mandatory 5 articles and get out. How can we, as librarians, make this work matter to the students and (maybe most importantly) to the instructors?

Rebecca – glad it hit home with you. Great question – how does DH impact or interact with the library user? To be honest, I think it might not play as much of a role for the user you describe; there will always be those who only want the minimum that we can provide. But! As the library evolves, better articulates what we can/want to do, and as the work we do changes, I’d hope that the entirety of library users (academic, public, special, ect) would come to expect more.

A good, solid example – The Visualizing Emancipation project. I’d bet that this would be incredibly valuable to American History 101 courses and that 99% of students, grad students and faculty don’t even know about it. So, (y)our role then is to be familiar with these tools, and promote them as we would any other resource. Maybe instead of giving the student 5 articles, you give them 4 and one text-mining tool.

Thanks for this outstanding and thoughtful article.

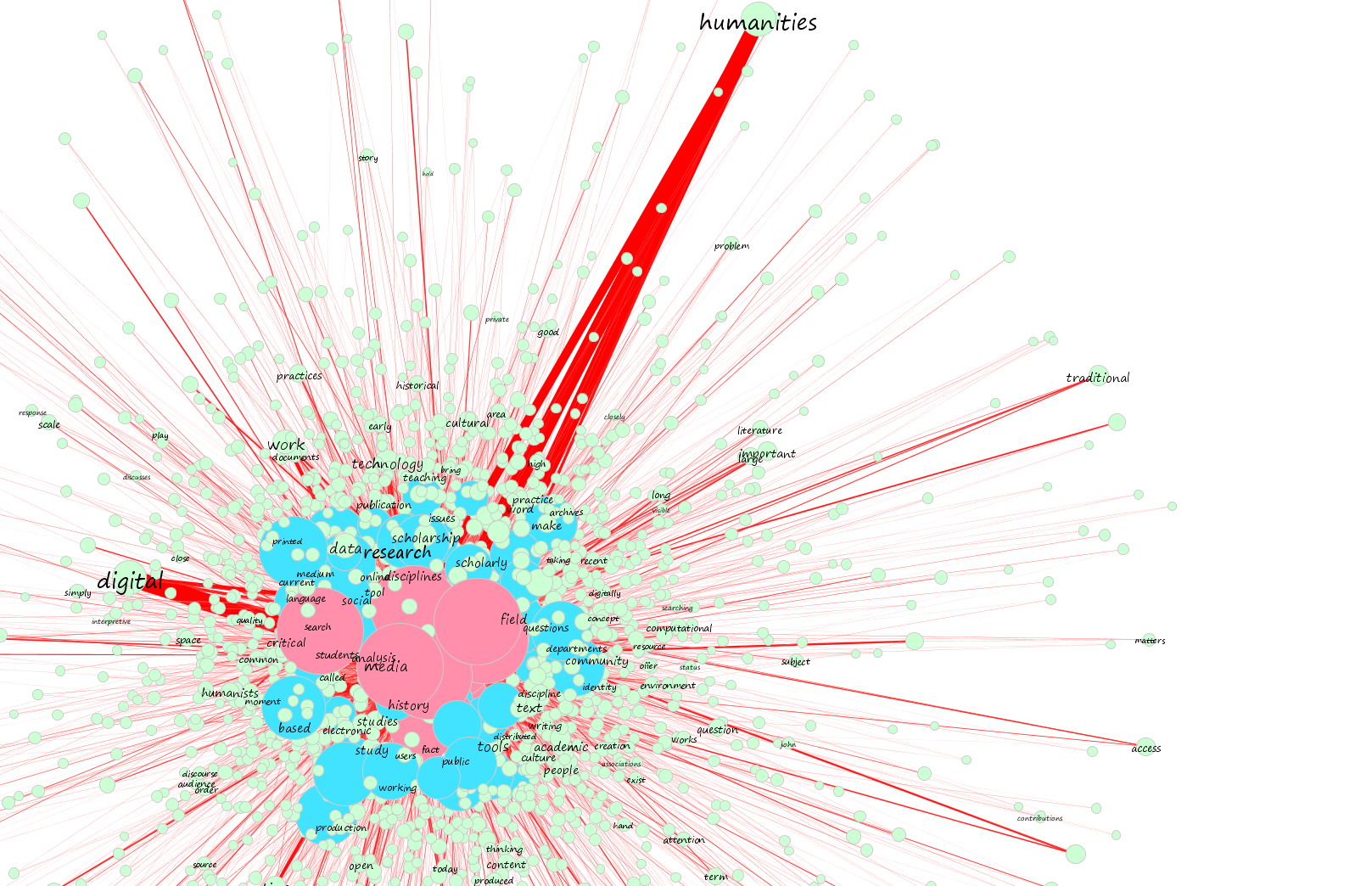

I’d like to add something that surely qualifies as minor trivia — but trivia with a message, I hope. Your provocative question, “Where’s the library?” in Elijah Meeks’s stunning “Comprehending the Digital Humanities” visualization, actually has a very simple answer: the library is the place where the data for this very visualization was collected, analyzed, and studied, and where the visualization itself created. You see, Elijah works not only at Stanford: he works in the Stanford Libraries. (This is a nice illustration of the Wiegand mantra you quote: we must see the library in the life of the DHer.)

An even more trivial (but also illustrative) fact is that a huge glossy print of this very same visualization hangs on my office door (which is in the middle of the main library at Stanford). Elijah is my close colleague in the Stanford Libraries, and we, along with at least a half dozen others — or maybe it’s a couple dozen, depending on the day and whatever their current project is — all count ourselves as true blue, dyed in the wool DHers.

This is all simply to concur wholeheartedly with your thesis that “libraries and digital humanities have the same goals,” and with your advice that we involve ourselves more actively in DH projects, that we advocate more strenuously for expanded roles in the digital scholarship happening around us, and that we become more active as producers, creators and scholarly collaborators in the DH endeavor.

(Or at the very least that we boldly post provocative and colorful DH research on our office doors as a proclamation that, yes, DH is now — and always has been — very much in the library.)

Glen, Digital Humanities Librarian

(Say it loud, say it proud, &c.)

Pingback : The Lazy Librarian

Pingback : Stewart Varner

Pingback : Library Support for DH | Stewart Varner

Hey Micah!

Amazing post in an amazing venue. The comment I originally started got too long so I stuck it on my till-now sorely neglected blog.

check it out here: http://stewartvarner.wordpress.com/2012/06/28/library_support_for_dh/

I’m honored Stewart. Thanks for taking a look at it. Here’s to more and further great work as we figure this all out!

Possibly minor correction: your link to the Digital Thoreau site is “built in text-mining tool,” but VM (Versioning Machine) is collational software, not for text-mining.

I think you are right that DH offers greater opportunities for involvement by librarians, though I wish you had been a bit more concrete than polemical. Your rousing “cast off our chains!” rhetoric runs the risk of reinforcing a divide between librarian-work and research proper.

Strongly asserting that librarians need to do digital work without ever providing referents can lead to the reading I had when first going over your piece: librarians need to become scholars; scholarship is progressive, librarianship is servitude. But talk to some folks doing DH (and Stewart Varner’s post gets to some of this) and they don’t need more scholars, they need people who have metadata, preservation, and project management skills. I would argue that librarians who want to be involved in DH can do so by promoting skills they have as librarians, not by trying to be scholars or on the basis of non-librarian subject knowledge.

Personally, I’d like to see librarians who are excited by DH do a better job of showing how librarian skills bring a lot to the table. One possible avenue would be critically assessing DH projects, say on a DH&Libraries blog of some sort.

Pingback : DCW Volume 1 Issue 6 – DH Mad Libs

Micah, Thanks for the great article and a wonderful collection of links! You raise a good point about getting librarians to change their perceptions. It’s difficult for any group to fundamentally change how they view themselves, and librarians certainly aren’t notorious for such feats. In this regard, Stewart’s response/post is particularly useful because it outlines concrete steps that we can take to begin supporting DH in our libraries.

DH can be a big messy world and is often tied to big messy issues (copyright, open access, tenure and promotion, etc), so I found it helpful to start with what I knew – I’ve worked with Omeka before and did my undergrad in history, so I asked a history prof if he wanted to create an Omeka site for one of his courses. It’s not groundbreaking but it’s something.

Pingback : Digital Humanities « Amanda Cowell

Pingback : Library Support for DH « Stewart Varner

“But to be effective in the research context the librarian is going to be a lot more specific, and more directly involved with the researcher at the outset of a project, helping them put together a set of questions, data, and tools that will move a discipline forward, rather than waiting until a scholar shows up at the library with a problem.”

One Culture: “Urgent, Pointed, and Even Disruptive”

Pingback : Navigating DH for Cultural Heritage Professionals, 2012 edition | Lot 49

Pingback : Proposed Grad Course for 2013-2014: Practicing the Digital Humanities (Draft) » Roger T. Whitson, Ph.D

Pingback : Mike D'Errico , On Preservation and “Re-Representation”

Pingback : Libraries as Laboratories for DH | this is a DH blog