Running the Library Race

In Brief: This article draws a parallel between fatigued runners and overworked librarians, proposing that libraries need to pace work more effectively to avoid burnout. Through an exploration of cognitive science, organizational psychology, and practical examples, guest author Erica Jesonis offers considerations for improving productivity and reducing stress within our fast-paced library culture.

“Feet” photo by Flickr user Mark Steele (CC BY-ND 2.0)

I recently ran my first half-marathon and did pretty poorly. What upset me the most was not my pathetic finish time, but rather the chipper group in front of me that completed the race by alternating bursts of running with stints of walking, a method that boasts impressive results but gets little respect amongst serious runners (Parker-Pope, 2009). My group was determined to run the whole race, no matter what. I watched the walk-runners in envy as they chit-chatted, picking up their pace when their watches beeped for them to run. In all, they walked a large portion of those grueling 13.1 miles, and despite my continued running, I never caught up with them. I’m sure they crossed the finish line far ahead of me with smiles and high-fives, making plans to celebrate with margaritas; I trudged across and wanted to die.

After the half-marathon, I began researching walk-run techniques, and I began to wonder if the same techniques might help make my work life more productive, too. Common sense dictates that physical work is easier and more enjoyable when you take breaks, alternate muscle groups, and vary pacing. Teachers apply the same methodology to pace their instruction, starting with warm-ups, building to more intense tasks, then backing off to allow creative and cognitive replenishment. These concepts may be intuitive when it comes to workouts or pedagogy, yet they are strangely foreign to the working world, particularly to the library world renowned for its never-quit work ethic. We simply don’t give our minds the same consideration that we give our bodies.

Public libraries in particular are still nursing fiscal sprains from the past few years while trying to rally energy for the next budget cycle. Worse yet, forecasts show that this library race we’ve all been running may just turn out to be an ultramarathon. The American Library Association (ALA) reports that “despite some promise of budgetary relief, the extraordinary demands for service continue to outpace available funding needed to respond to those demands” (“Public Library Funding Landscape,” 2012, p. 10). Simply put, we have more work to do with less money and the scenario is not going to change anytime soon. Adding to that, many library staff are already stretching to cover positions that were eliminated or left unfilled.

This complaint is far from new, so why do I even bring it up? Perhaps because my half-marathon failure made me realize that our coping mechanism is tragically flawed. We’re trying to work faster and harder to show that libraries are strong, able to cope, and able to succeed no matter what the future brings. But is this new pace sustainable? Or is it actually dangerous and self-defeating?

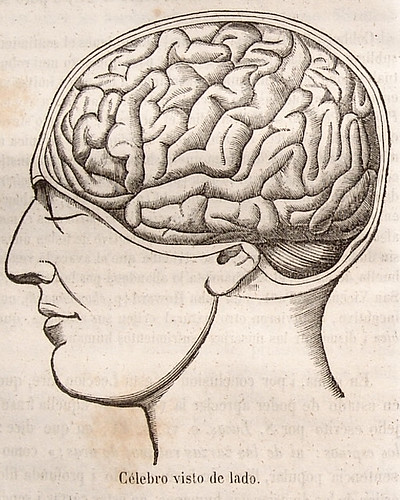

What Your Brain and Your Muscles Have in Common

The brain is the lofty tower of our personalities, thoughts, memories, and existence, yet it often acts like a much simpler muscle, performing best when given rest and variation. Just like a muscle, the mind is prone to its own types of fatigue such as diminished mental performance, distractedness, impatience, and a “measurable decline in directed attention capacity” (Cimprich, 2007, slide 8). Similar to a computer, the human brain effectively shuts down when overtaxed, and “if the capacity of working memory is exceeded while processing a body of information then some, if not all, of that information is lost” (Cooper, 1998, section 2.6). I think of this as the “spinning wheel of death” that your computer gives when it looks like it’s processing a task, but it’s really just stuck and you end up having to do a hard reboot. Our brains do the same when overburdened, particularly with extremely high cognitive load. The more you try to do at once (multitasking those emails, attending to that grant proposal, filling out your timesheet), the more likely you are to overload your brain’s attentional and functional capacities.

As tempting as juggling seems, humans struggle to stay focused when doing or thinking about more than one task. In fact, even when we don’t think we’re “paying attention,” we are, just to something else. Those pesky light-bulb moments that distract us from our object of focus are known in the scholarly world as Task-Unrelated-Thoughts, or TUTs (Ariga & Lleras, 2011, p. 439). We are all woefully familiar with TUTs (and you’re probably having some right now), but what do you do about them? Intellectual tradition admonishes that we need to be Master of our attention, to give it a firm spank and tell it to quiet down, but those TUTs may be a helpful warning sign that your brain needs a rest. The key to maintaining the brain’s focus over time isn’t iron-grip discipline. The solution is much more pleasant and perhaps even surprising: to take a break or switch tasks.

Imagine you are a cashier at the local grocery store. Every time you scan an item, the register makes a loud and annoying “BEEP.” That noise is meant to get your attention, and yet within a few hours or even minutes, your brain does an incredible job of tuning out that noise so it can focus on other input. We see this in all aspects of our lives. For example, you probably don’t feel yourself wearing clothes right now and you might even be able to ignore that huge mess on your desk. Research shows that “all perceptual systems show habituation effects” (Ariga & Lleras, 2011, p. 440). Basically, what we see, hear, feel, smell, taste, and even understand tends to lose intensity the more we are exposed to it.

This same concept holds true for your attention in a way that may seem paradoxical. The harder you try to pay attention to something—to think really hard about that work—the more “habituated” your brain becomes to the goal (Ariga & Lleras, 2011, p. 440). The longer you focus, the more susceptible you become to those annoying, interrupting TUTs. This “habituation” may seem like a faulty system at first, but it is a necessary human coping and efficiency mechanism. Consider all the annoyances we block out daily, as well as the tasks that the brain is able to quickly compartmentalize and routinize, requiring very little “active” thought at all. But what about that challenging project you are slaving over? You don’t want your brain turning off. The remedy? Taking a break and walking away from the task at hand.

In the study, “Brief and Rare Mental ‘Breaks’ Keep You Focused: Deactivation and Reactivation of Task Goals Preempt Vigilance Decrements,” researchers found that “vigilance decrement occurs because the cognitive control system cannot maintain the same goal representation active over prolonged periods of time” (Ariga & Lleras, 2011, p. 442). This means that the brain’s ability to keep a goal at top priority diminishes over time. By pausing your work, or even switching tasks for a short time, you can trick your brain into keeping that goal in the number 1 slot, to “preempt full goal habituation from occurring by re-strengthening the goal’s activation level upon resumption of the vigilance task” (Ariga & Lleras, 2011, p. 442). Letting go of the goal and then picking it back up again actually makes your mental grip stronger.

This “habituation” phenomenon is strikingly similar to muscle fatigue: ask your arm to hold a 10-pound weight straight up in the air and it feels easy at first. A few minutes later, you’re struggling and your arm feels positively useless. If you measure the total length of time you held up the weight, it doesn’t amount to much, but break the exercise into shorter segments, or repetitions, and you can hold that weight up for a very long time collectively. Although the brain isn’t a muscle, it certainly performs like one in this respect. Ask it to pay attention without a break, and it quickly falters. Give it intermittent rests or changes, and that brain can be much more focused over the long-term, increasing your productivity and sharpness.

Taking frequent breaks isn’t always practical (or apt to make your boss happy), but the British have a wise adage: “Change is as good as a rest.” Varying the type of work you do, especially alternating between tasks of high cognitive load and low cognitive load, can be a powerful way to restore the brain’s directed attention. Switching briefly into a task that requires less deep thinking, such as cleaning up your email inbox, can be a productive way to pace your work. This act of mental downshifting replenishes the strength of your attention by moving “away from tired cognitive brain structures that have become fatigued through overuse” (Cimprich, 2007, slide 10), allowing the brain to recharge. Think of this technique as a type of circuit training for your brain.

Productive Procrastination

I’ve been exploring this concept through studies on cognitive science, but it also resonated with me as a former English teacher. My students were always thrown off by Shakespeare’s use of comedic relief in his most tragic plays. After Ophelia’s death in Hamlet, the grave diggers trade ridiculous jests about topics like mortality and suicide. To most teenagers, this dark humor makes no sense at all. They know that Hamlet is about to discover that his girlfriend is not only dead, but probably killed herself, and he probably drove her to it. Why would Shakespeare choose to make this funny? As a master of human nature, the Bard knew that his audience needed a break. They needed some perspective from the tragic, because the play was about to get a whole lot more sad. Writing in that break was pivotal not only to retaining the audience’s attention, but to making the end of the play that much more dramatic and effective.

Other literary greats also tout the creative benefit of the break. Ernest Hemingway advised that “the best way [to write] is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next…That way your subconscious will work on it all the time” (qtd. in Phillips, 2004, p. 42). Have you ever woken up in the morning with a solution to a problem that yesterday seemed unsolvable? Our brains sometimes work best when we think we’re not thinking at all, but that magical equation can’t happen without time, rest, and perspective. True innovation and creativity often come after periods of what seems like non-work as, in the background, our brains are able to synthesize and weave thoughts we aren’t consciously “thinking.” In one of my favorite episodes of Mad Men, Don Draper is criticized for his department’s nontraditional working habits and fires off this panache-filled retort: “We do this better than you, and part of that is letting our creatives be unproductive until they are” (Gordon, 2009). Creativity may look messy or unproductive at times, but can actually speed up performance in the long run (Leybina, Ong Hui Zhong & Kashapov, 2011, p. 120).

Breaks or creative pauses may seem like procrastination, a dirty word in our proactive library culture, but reflection can mean the difference between making a good decision and a really bad one. In ancient cultures that prized time spent contemplating, procrastination was encouraged and lauded; it only became vilified only after the rise of the New World Puritan work ethic (Gambino, 2012). In his book about procrastination aptly entitled Wait: The Art and Science of Delay, Frank Partnoy advises that waiting helps us to make better decisions:

“People are more successful and happier when they manage delay…We will always have more things to do than we can possibly do, so we will always be imposing some sort of unwarranted delay on some tasks. The question is not whether we are procrastinating, it is whether we are procrastinating well” (qtd. in Gambino, 2012, para.12).

Partnoy overviews recent research into professional athletes and even people on first dates that found delaying to be a critical part of successful decision making (Gambino, 2012). We think of procrastinating as avoidance or failure, but used appropriately, it’s a successful method for giving your brain vital processing time. When our work lives start to overwhelm us, pausing, varying work, and even strategically procrastinating can be powerful tools to create a productive and sustainable pace. But if we choose not to heed this advice, what happens? The brain may dump excess information out, but many people also experience a worse phenomenon: the choke. That feeling of looking at your to-do list and seeing so many tasks that you feel your brain shut down.

As science writer David DiSalvo explains:

“The human brain is a powerful problem-solving and prediction-making machine, and it operates via a multitude of feedback loops. What matters most in the feedback loop dynamic is input—what goes into the loop that begins the analysis-evaluation-action process, which ultimately results in an outcome. Here’s the kicker: if your input shuttle for achieving a goal lacks the critical, emotionally relevant component of belief, then the feedback loop is drained of octane from the start. Another way to say that is—why would you expect a convincingly successful outcome when you haven’t convinced yourself that it’s possible?” (2012, para. 4).

If your brain consciously or subconsciously knows that you’re asking for too much, it may play possum on you. Certainly, there are times when we have to push through and do the work, no matter what. But when that choke feeling becomes more and more frequent, our brains may be sending an important override to stop us from running down that path marked “burnout.”

Tired Brains, Tired Organizations

“216036” by Flickr user Biblioteca de la Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias del Trabajo Universidad de Sevilla (CC BY 2.0)

As an industry that boasts an incredibly talented but increasingly stressed pool of people, libraries are in danger of burning out en masse. Research on workplace stress identifies six key areas related to burnout: “workload, control, rewards, community, fairness and values” (Maslach, 2011, p. 44). Like knobs on a mixing board, we can achieve a certain harmony by using some factors as cushions or compensation for others. For example, employees may accept a job that is high on workload and low on pay when those areas are evened out by a strong community and a workplace of integrity. I believe we as library professionals are uniquely blessed to work in a field that deeply honors community, fairness, and values—we share information freely, love to collaborate, and we go to great lengths to treat our patrons equally. Those factors are integral to our collective character and have been our parachutes in these free-fall years. But are these factors enough in a library landscape that for many keeps growing higher on workload and lower on rewards? Despite our heroic advocacy efforts, budget malaise may linger for years to come. ALA reported in a recent press release that salaries for public and academic librarians are largely flat again for 2012, adding even more stress to the burnout equation (2012).

When put under increasing pressure, the values that have kept us afloat through these lean years become tainted with cynicism, one of the most concerning risk factors of burnout (Maslach, 2011, p. 46). Marathons and long races are meant to be sporadic occurrences, with ample rest afterwards to avoid injuries. With both exercise and work, you can motivate yourself to work much harder than usual when you know the end is in sight, but what if there is no end? Or if the end is simply beyond our means? What happens when the “vision” becomes a culture in which we are expected to work harder and faster all the time, forever?

Enter the manic organization. A slightly manic person can be awe-inspiringly productive at first, but that constant frenzy of activity becomes their ultimate ruin. They lose the ability to make the most basic decisions wisely. Left untreated, they risk death from exhaustion or suicide (Royal College of Physicians of London, 2008, p. 238). Similarly, the manic organization can slowly march its way into the ground through perpetual activity as the humans that run it suffer the consequences of physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion. Libraries are doing more than ever for more patrons, but the tenacious problem of offering so many services and materials and opportunities is that it becomes difficult to take a pause, especially when reduced budgets translate into reduced staffing.

Pausing is even more challenging when our work culture, a culture we’ve been forced into by our dire need to prove our value, focuses on results to the detriment of the process. Effective marketing for libraries is essential, but is the constant stress on results causing us to devalue the necessary downtime? What about brainstorming time? Replenishment time? These aren’t the kinds of activities we want to list in our advocacy campaigns or our annual reports, yet in the exercise and scholarly worlds, coaches and teachers know that these are the foundations of success. Cutting them back would be unthinkable.

Conclusion

Looking realistically at how long libraries’ budgetary challenges may go on, we need to learn to pace ourselves for this race. One particularly volatile combination of risk factors is that of high workload with low levels of control (Sargent & Terry, 1998). A powerful way to relieve some of this pressure is to create control where we can, giving employees more tools to pace their work and more say over how their work is executed. In fact, research on productivity identifies work pacing as one of the key ways to insulate against other stresses. “A person who has too much to do is likely to be able to handle this stress if the job has some flexibility in terms of its allocation of time and energy to tasks” (Sargent & Terry, 1998, p. 231). In a workplace that can’t afford raises or promotions, workers may find relief in gaining flexibility of hours or some ability to work from home. A healthy organizational culture can set the model for effective pacing by coordinating collective down-times after periods of peak activity. For example, administrators can discourage programming in the month after summer reading or give more time to catch up on personal projects once new student orientation is complete. Leaders can foster a workplace in which thoughtfully saying “no” is accepted and encouraged (Ford, 2009). These measures shouldn’t be thought of as doing less or scaling back, but purposefully strengthening the organization so that future initiatives are successful.

In the half-marathon, had I paced myself better to anticipate those hills, I could have preserved my energy. Better yet, had I put my pride on the shelf and taken a few breaks, I could have run faster and finished with a better time. Overworked people of the library world: it’s time to pace ourselves so together we can survive to the finish line.

Many thanks to Kim Leeder, Denise Davis, and Paula Richwine, P.T., D.P.T., for their helpful feedback on prior drafts. Several others graciously read earlier versions and listened to my nebulous ideas – thank you Kevin Urian, Laura Metzler, Lee O’Brien, Drs. Aaron and Katherine Karmes, and in particular, Leah Youse.

Further reading on this topic:

- Our Librarian Bodies, Our Librarian Selves

- What Do We Do and Why Do We Do It?

- That’s How We Do Things Around Here

- Struggling to Juggle: Part-Time Temporary Work in Libraries

- The Importance of Thinking about Thinking

References

American Libraries Magazine. (2012). Public library funding landscape (Digital supplement Summer 2012). Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/research/sites/ala.org.research/files/content/initiatives/plftas/2011_2012/plftas12_funding%20landscape.pdf

American Library Association. (2012). Survey results indicate salaries for librarians in 2012 flat – and in some cases lower [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/news/pr?id=11243

Ariga, A., & Lleras, A. (2011). Brief and rare mental “breaks” keep you focused: Deactivation and reactivation of task goals preempt vigilance decrements. Cognition, 118, 439-443.

Cimprich, B. (2007). Attention restoration theory: Empirical work and practical applications [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.umb.no/statisk/greencare/meetings/presentations_vienna_2007/cimprich_cost_pres_71007.pdf

Cooper, G. (1998, December). Research into cognitive load theory and instructional design at UNSW. Retrieved from http://dwb4.unl.edu/Diss/Cooper/UNSW.htm

DiSalvo, D. (2012, August 07). The 10 reasons why we fail. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/daviddisalvo/2012/08/07/the-10-reasons-why-we-fail/

Ford, E. (2009, December 16). How do you say no. [Web log message]. Retrieved from https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2009/how-do-you-say-no/

Gambino, M. (2012, July 13). Why procrastination is good for you. Smithsonian magazine. Retrieved from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/Why-Procrastination-is-Good-for-You-162358476.html

Gordon, K. (Writer) (2009). The fog [Television series episode]. In Weiner, M. (Executive Producer), Mad men. AMC.

Leybina, A., Ong Hui Zhong, A., & Kashapov, M. M. (2011). Active or lazy: What motivates workplace performance. Psychology research, 1(2), 114-122.

Maslach, C. (2011). Burnout and engagement in the workplace: New perspectives. The European Health Psychologist, 13(3), 44-47.

Parker-Pope, T. (2009, June 2). Better running through walking. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/02/health/02well.html

Phillips, L. (Ed.). (2004). Ernest Hemingway on writing. New York: Scribner.

Royal College of Physicians of London. (2008). Neurology, ophthalmology and psychiatry. London: Royal College of Physicians of London.

Sargent, L. D., & Terry, D. J. (1998). The effects of work control and job demands on employee adjustment and work performance. Journal of occupational and organizational psychology, 71(Sep), 219-236.

Brilliant. Love the post and the reflection. We don’t do this enough in our society. One aspect that isn’t covered in the article is the practice of mindfulness to bring relief and focus in our work environments. In my space, I like to bring my full attention to all my activities and learn to train the mind. Cultivate concentration. Though it takes practice, it isn’t that difficult after a time and it can result in a much cooler and calmer outlook in the work environment. Like what you wrote, stopping is a key aspect to developing this mindfulness and concentration. I look forward to more comments and thoughts on stabilizing our frantic lives.

Thanks, Kenley. I really appreciate your additional thoughts, particularly how like work pacing, mindfulness can bring both relief AND focus. Your comment reminded me of the French tradition of using the fountain pen. It’s at times messy, it takes longer to write, but it brings a purposeful slowing down and appreciation of the beauty and meaning of the task. Thanks for reading and sharing!

This is an excellent article. It is so typical of us to do more with less and has somewhat become a mantra and a badge of pride. I loved your points about leadership stepping in and doing the things necessary for staff to recover after summer reading or creating an atmosphere where staff can say no. I actually had a boss that insisted staff take September off from programming and there was actually a bit of grumbling; but, in the long run it was great because everyone was forced to slow down, take a breath and regroup.

I had an occasion where I visited with a neuropsychologist and he told me something I didn’t know. Sleep deprivation, even small amounts like an hour here or there, can produce symptoms that are similar to brain injury. Sleep is when your brain rests and heals from stress, too much stimuli, and being overworked.

He also told me that pausing for one or two minutes, eyes closed, clearing the mind of thoughts using a phrase (he suggested: calm. quiet.)is actually extremely useful in helping your brain concentrate effectively. He suggested doing this once an hour or more frequently during periods of high concentration.

Thanks so much, Ann. I am fascinated by what you learned from the neuropsychologist – I will look into this more! His tips sound profoundly helpful and very much in line with the research used for this article. Thanks for sharing with us.

I’ve stopped doing other peoples’ work this year. This has been hard for me, but it’s been even harder for those whose work I did and those who assumed I would do other peoples’ work. But they are getting the message. We run libraries on the backs of women with part-time jobs who have to have someone else supply them with housing and health insurance. And the more we do, the more will be expected of us. Stop the insanity!!

Sarah – you are awesome and brave! Have you encountered a lot of backlash? I agree that collectively, one of the best things we can do for the profession and for our colleagues is to be really honest about what workload is acceptable and manageable…

Librarianship is not difficult work. It’s not like running a marathon.

Linda, please grace us with an article! I would love to hear you expound on your view that “Librarianship is not difficult work.”

Pingback : | We Love Gratitude : Be Grateful

Pingback : Surviving the Rat Race « Civil Civil Servant

Erica, as someone who compulsively edits random magazine articles, pouncing on misplaced apostrophes and misused pronouns, first of all let me say–great writing. I think you’re right, that most sustained effort of any type is enhanced by thoughtful, planned breaks. It’s interesting that apparently the best type of training is also “interval” training, which incorporates lower intensity with full-on effort, and apparently maximizes muscle gain.

Very interesting, thanks. I see the rationale in switching tasks and giving your brain a break, but I often find that the opposite tactic works better. If I have too many tasks to finish, I try to cycle between them all and feel overwhelmed. It’s much easier if I pick one, completely block out the others, and work on it steadily until it’s done.

I think one of the unintended consequences of just working harder is that it can seem to justify the cuts to those who made them. “See they didn’t need that money/staff/space they’re doing just fine without it”.

My city has grown rapidly and the elementary schools are very crowded yet there has been real reluctance to build more schools. Instead of converting the music and computer room and storage space to classrooms what would happen if they rented space from the church or rec center down the street. All of the parents whose kids were being housed “off campus” would be aware in a very dramatic way of the overcrowding of the school. Questions start to be asked when members of the church realize school kids are using their space etc. Perhaps sometimes dramatically not doing it makes the point better then anything else.

Excellent article, and incredibly timely. As you counsel in the article, for the last couple of months I’ve been incorporating more interval techniques into my life.

At work, I’ve been using the The Pomodoro Technique and it seems to be increasing productivity and reducing anxiety. I haven’t read the Pomodoro book, so I may not be using correctly, but so far so good. I use a website called Tomato Timer to time my intervals.

I’ve also incorporated more interval training into my exercise routines (and daily or near-daily exercise seems to help me sleep better and reduce stress). I’ve committed to going on one long run per week, and I try to take yoga classes when I can. But on the other days I’ve been trying to go on a short run or do a Tabata routine.

On the short run (~2 miles), I incorporate as many one- or two-block long sprints as I can manage after I’ve warmed up in the first mile, so the whole thing generally takes about 15 minutes. The Tabata workout takes 8 minutes: 2 minutes of warm up, 8 sets consisting of 20-second high-intensity exercises paired with a 10-second rest, and 2 minutes of cool down. On days when I can’t fit a yoga class or longer run into my schedule, it’s nice to have exercise options that I definitely can find time to do.

I hope these techniques might be useful to others. I’m also interested reading suggestions for similar techniques, either at work or in the rest of my life.

Pingback : a timely piece on burnout in libraries | Yezbick.com: If It's Weird, Flip It Over and Check, It Might Be a Yezbick

First of all – congratulations on the half-marathon – my running career is only re-starting now after what I call “The library Stress & Doughnut Years” – my personal bests in the library and on the road were back in the 80s but I am hanging on as a Master, a veteran and coping with deafness, depression and renal failure (Transplant 1995). Perhaps the problems of burnout in librarians might be helped by reducing the difficulties caused by poverty and promotion, fundamentally, the absence of promotion. In the meantime we put one foot in front of another, and smile….

Chris – thanks for your comments. I love your decription of the “library stress and doughnut years” – so true!

Pingback : Tensegrities » Blog Archive

Pingback : Librarian Blogs: A Peek into the Career | slm508mav