“All I did was get this golden ticket”: Negative Emotions, Cruel Optimisms, and the Library Job Search

In Brief

Drawing from survey results and interviews with recent job seekers, this article investigates the effect behind defeatist attitudes, anxieties, resiliency narratives, and intimacies that are central to librarian successes and failures. Connecting these narratives with Lauren Berlant’s cruel optimism, we explore the dangerous attachment LIS job seekers have with the field. While library schools and library associations promise a good life with financial stability and the possibility of upward mobility, it is often out of reach for nearly a third of LIS graduates. To explore job seekers’ emotional experiences during the LIS job search, the authors looked specifically at the first job search from the perspective of graduate students as well as from those already in positions. Our survey yielded over 900 participants and we conducted 18 in-depth interviews. The results provide both confirmation for themes already discussed in librarianship, as well as new insights for work to be done to support new colleagues entering the field.

By Dylan Burns and Hailley Fargo

Introduction

For those finishing graduate work in library and information science (LIS), being on the job search can be a scary and yet necessary result of the degree. The expectation is a job at the end of the library degree, and this, as most of us in the field know, is not always the outcome. The difficult job search has become a rite of passage and depending on the library job we want, the location(s) we are willing to relocate to, and the positions available in the field, our searches can last a few months, or stretch beyond a year. In the end, the longer the job search goes, the more difficult it can be to “keep our chins up” or practice resilience. Throughout our searches, we expend emotional energy to find job postings, write personalized cover letters, prepare for phone interviews, and save up funds to travel to on-site interviews, all with the hope of employment in a library at the end.

This article aims to explore job seekers’ emotional experiences during the LIS job search. We wanted to look specifically at the first job search, both from the perspective of graduate students, as well as from those who had been in positions for a period of time. From the emotions throughout the job search, we wanted to know about the implications those feelings had on our thoughts around the field of librarianship as a whole. The job search, while stressful, is a process intertwined with possibility and hope in equal amounts to the desperation we often see when seekers cannot find employment. For job seekers, even the successful ones, the search is an attachment to a field that is perceived to be dying by the public, with fewer new jobs than new graduates, and an unstable future. The paper that follows explores the survey and in-depth interviews we conducted throughout 2018 and suggests directions for the field to take moving forward.

Job Market Optimisms and Pessimisms

The LIS job market in the current political and economic climate is fraught and full of peril for many new professionals. When attempting to tackle anxiety in the job search it is important to understand the historical and political underpinnings of this specific moment for the field of librarianship. There has been research exploring the reliance on “fit” as a criterion for job selection (Farkas 2019 and 2015; Cunningham et al 2019), diversity and the LIS job market (Morgan et al 2009; Berg et al 2009; Kim and Sin 2008; Vinopal 2016; Hathcock 2015; Galvan 2015), the precariousness of the future of libraries for job searching (Grady 2009), the role of mentorship in successful job searches (Lacy and Copeland 2013), and the need for technological training and job experience outside of coursework for success in searching (Eckard el al 2014; Roy et al 2010). Yet missing from this picture of the job search is an exploration of anxiety and emotions felt by new graduates and job seekers in this precarious market.[3]

In the Fall 2017, Library Journal (LJ) published its annual Placements & Salaries report on graduating library students. It found that 4,223 new LIS graduates finished their degrees during 2016-2017. LJ conducted a survey of recent graduates (n=1,426), and found that overwhelmingly these respondents were employed full time (80%). However, only 67% of those employed were working full-time in libraries. Of 67% employed full-time within libraries, an additional 17% of those participants held part-time status in libraries, many holding several jobs to make ends meet with an average of 1.6 part-time jobs per library school graduate. While the report cited the rise in wages for new graduates, it hinted at deep dissatisfaction in the community. The report’s authors state:

Overwhelmingly, unhappy graduates point to underemployment issues, including low wages; lack of benefits; having to settle for part-time, temporary, or nonprofessional positions; or having to piece together two or three part-time positions to support themselves. Several report being frustrated about carrying student debt for their LIS degree without being able to use the degree in their current positions (Library Journal Placements and Salaries 2017).

While we do not wish to get into potential issues with Library Journal’s approach, it is hard to see this sampling (33% of the total 4,223 graduates) as representative of the whole. It is possible that LJ is oversampling successful job seekers, as those with difficulties finding employment may not contribute to this sampling. Did libraries create enough jobs for the 4,223 graduates that year? According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) (2019), the field is only projected to create 12,000 new jobs in the next ten years, and have a replacement rate per year of 14,500 over the next ten years. Within that 14,500 number, 7,900 are retirements and 5,400 are librarians leaving for other fields, with an estimation of 1,200 new jobs created. It is difficult to imagine that many of these 7,900 jobs will represent open entry-level positions. This is, of course, speculation on continuing trends, and economic trends are always hazy to begin with.

Investigating just the academic librarian job market, Eamon Tewell (2012) found that only 21% of advertised jobs between September 2010 and September 2011 counted as “entry level,” requiring less than a year of experience. Furthermore, even for jobs with expectations of less than a year of experience, 76% were being filled with candidates who did not meet the criteria as entry-level (meaning they had more than one year of experience in libraries) (Tewell, 2012). Unfortunately, these datasets only exist for academic librarian openings, mainly due to tenure and promotion requirements within this sphere of librarianship. The field has not seen a systematic exploration of opening and entry-level positions across the different types of librarianship. The survey and interview data we collected suggest that there are more graduates than entry-level positions across all subsets of librarianship. We saw in our research that hope and luck are necessary parts of the library search, and library students have often had fears calmed by ongoing promises of better markets in the near future, post-recession and post-retirement.

Cruel Optimism, Hope, and Challenging Job Markets

In order to fully understand how emotion and anxiety specifically impact LIS job seekers, our research project relied heavily on frameworks developed by literary critic Lauren Berlant. Berlant terms the growing societal and cultural anxiety stemming from neo-liberal dissatisfaction “cruel optimism.” For Berlant, “cruel optimism” terms an attachment “when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially” (Berlant 2011, 1). Attachment for Berlant is always inherently optimistic, and the futures imagined through attachment are based on fantasy in a somewhat neutral sense. Yet the fantasies that drive students and job seekers are becoming more and more frayed (Berlant 2011, 3). This is particularly poignant in promises of “upward mobility, job security, political and social equality” which Berlant explains are “the set of dissolving assurances [that] also includes meritocracy, the sense that liberal-capitalist society will reliably provide opportunities for individuals to carve out relations of reciprocity that seem fair and that foster life as a project of adding up to something…” (Berlant 2011, 3). For LIS students the degree is an investment of time, money, and emotions, often with a stated goal of a professional library job. For librarians, a “good life” could mean many things. It may mean a tenure track job at an R1 institution, a secure position at a public library, or recognition in the field. A student graduating in the next few years is promised, in many ways, “a good life,” yet that attachment, however optimistic, is strikingly bleak when countered with the difficult road that many job seekers must walk for self- and job- satisfaction.

Whatever a “good life” entails is individual, yet, as Berlant and many others have pointed to, it is ingrained in the American experience. Berlant writes that some might “call the fragilities and unpredictability of living the good-life fantasy and its systemic failures ‘bad luck’ amid the general pattern of upward mobility, reliable intimacy, and political satisfaction that has graced liberal political/economic worlds since the end of the Second World War” (Berlant 2011, 10). Many of our respondents pointed to luck as a factor in job search success and failures. One, a full-time librarian who spent 8-9 months searching for a full-time position, responded that:

I’m still friends with a bunch of people that I did the masters program with, and it’s almost two years since we graduated. And it’s just now that some of them are finally getting a full-time librarian position. So, that is another, there’s a few others that have just finally gotten them. So, seeing that wow, I feel really lucky that I was able to get a full-time position shortly after finishing.

Furthermore, because of the interlinkage between jobs and upward mobility, a central component of the “American dream,” the recent recession has hit confidence and outlooks especially hard. Aronson found that students identified new value in post-secondary education in the wake of the recession, with many of the interviewed subjects citing the job market as a driving force for graduate or professional degrees (Aronson 2017, 51). On the other hand, Aronson concluded that the lack of prospects after graduation may lead to a larger erosion in the “confidence in educational and work institutions.” (Aronson 2017, 55) Graduates often felt their professors, programs, and universities were out of touch with the current economic environment and fears of malemployment and unemployment were not to be assuaged by institutional support (Aronson 2017, 55). This is a theme that appears in our research as well.

The cruel optimism framework has been used quite successfully to explore the effect of job searching within fields like education, which, like librarianship, experience constant change, threat, and murky futures. Moore and Clark argue that teachers are cruelly optimistic not only because of the painful ramifications of “good life” affects, but that they are engaged doubly in the creation of good lives for their students and for the public good. Furthermore, the authors explain that teachers “may need to convince themselves of the possibility of helping to bring about the better world they embrace in spite of the fact that its translation/mutations into the terms and conditions of neo-liberal policy…may be working against the realisation of that vision” (Moore and Clarke 2015, 671-672). Specifically, Moore and Clarke are referring to educational policy which inhibits the change that teachers may go into their field hoping to encourage. We can see parallels in the way in which librarians butt up against counterintuitive restrictions on how public service is performed in this neo-liberal system.

Passions and Intimacies on the Cruel Market

For job searching in public service fields, especially those where jobs are limited, a tremendous amount of emotional labor is necessary for the application and interview process. In an article aptly titled “It’s Like Writing Yourself into a Codependent Relationship with Someone Who Doesn’t Even Want You,” Jennifer Sano-Franchini writes about the complex relationship formed between the applicant and the search committee, through the pretext of intimacy in the “tailored cover letter” to the meetings and meals between interviewees and interviewers, or the showing of “passion,” “loyalty,” or “commitment” to institutions they’ve just met (2016, 101, 108). The attachment here is cruel in that the high level of competition as well as the emotional energy required to perform interviewing tasks will, for most candidates, be for nothing, and as jobs are perceived as scarcer and scarcer they will continue to elucidate these “cruel optimistic” feelings. It requires an intimacy that is expected and often impossible to the point where the feigned knowledge of the institution becomes a sought-after trait for job seekers. The rejection letters for jobs, described by Sano-Franchini as bad break-ups and the common “it’s not you, it’s me” letters,” bring out this attachment that is fleeting and hard to reconcile. Sano-Franchini (2016) concludes:

There is a problem with the system when these sorts of experiences are widely felt, yet normalized and accepted as part of the process. There is a problem when, instead of critiquing our institutional practices, the quick fix seems to be to provide hoards of advice, directives, and tips for candidates to navigate—indeed, to survive—the job search, and the problems of the job market are dismissed as the result of larger political and economic issues. (119)

The expectation of a long and difficult search, combined with the grin and bear it attitude, comes up often in the interviews with LIS job seekers below and illuminates the compassion with which our field must come to terms if it doesn’t want to purely exist in cruel contexts.

Methods

Our project revolves around two research questions:

- In what ways do negative perceptions about the future of libraries impact the emotions of job searching?

- What are common feelings and concerns about the librarian job market and how do those impact the anxieties of first-time library job seekers?

In order to discover the answers, we employed a mixed methods approach. We started by creating a survey that we sent out internationally, with respondents primarily from the United States, Canada, and Australia. This survey was meant to capture feelings around participants’ first job searches, how they felt about the future of libraries, and also to find respondents who wanted to discuss their job searches further through in-depth interviews. Our survey was open from the end of February to the end of March 2018.

Participants were recruited via Twitter and listservs. At the end of the survey, respondents could indicate if they were interested in a follow-up in-depth interview. Over 200 people indicated interest in the interview. From that group, we had another screening survey in order to make sure we had a representative sample for our interviews. We chose to do in-depth interviews with no more than 25 participants. From our transcribed interviews, we analyzed the data and created codes based on the themes that emerged throughout.

In-Depth Interviews

Our selected interview participants talked to either author — in-person or over the phone — between April and July 2018. These interviews lasted anywhere between 30-60 minutes and were later transcribed in order to identify themes. In the end, we interviewed 18 people. Of our participants, 9 were in academic library positions, 3 were public librarians, 1 was a school librarian, 2 worked in special libraries, and 3 were graduate students on the job search.

We created a set of nine questions that we wanted to ask. The full set of interview questions can be found in Appendix A. As we coded for themes, we began to see the cruel optimism framework, especially for those still on the job search. These interviews helped to expand our perspective on the job search and demonstrated the ways that the LIS job search is frustrating, long, exhaustive, and time consuming.

Limitations

Our project has a few limitations. First, because we sought out our population through social media and listservs, we do not know our response rate. All we can say about this population is how they responded to the survey and the in-depth interviews we conducted. While these findings cannot be generalized to all LIS job seekers, we do think our findings indicate an interest in this topic and will help to start conversations within the field about the job search.

Once the survey went live and we began our interviews, we discovered a few questions that were not asked or were interpreted differently than we had intended. We did not include a question about the type of library the respondent was currently employed by or where they hoped to be employed. We also asked a question about where in the job search process the respondent was. Our choices were:

- Have been job searching for under 6 months

- Have been job searching for 7-12 months

- Have been job searching for more than 12 months

- Employed for 1-11 months

- Employed for 12-36 years (1-3 years)

- Employed for 3-5 years

- Employed 6 or more years

- Out of the job search

Originally, we thought this question would get us the information we wanted, but during the interview process, we realized that reality can be more complicated. This was especially true for respondents who were getting their MLIS degrees, respondents who were currently working in libraries and finishing their degrees at the same time, and those who had been on the job market consistently for a longer period of time. These gray areas made it difficult for respondents to easily choose an answer.

Additionally, we did not ask in the survey for information around the respondent’s race, gender, or ability. These issues came up during some of our interviews and would be a place to expand this research in the future. We acknowledge that people with marginalized identities are more likely to find themselves in crueler job markets with more limited geographical parameters and more expectations for resiliency throughout their search.

Results

We had 1,047 respondents start the survey and used the 907 completed surveys for our analysis. From those 907 responses, we had over 200 people indicate interest in an in-depth survey and 145 who filled out our secondary screening survey. All secondary survey results were reviewed and interview participants were selected according to status (graduate student) or library type (academic, public/school, special, and other).

Survey

The surveyed population cut across many lines of the librarianship job searching spectrum. The majority of participants reported that they held their job for at least a year. Many were in the process of searching for under 6 months (17%), searching for 7-12 months (6%), and searching for more than 12 months (7%), and a final 3% indicated they were out of the job search completely and were not looking for a library job. There were also respondents who had been employed for under a year (21%), employed for 1-3 years (19%), and employed for 3+ years (27%).

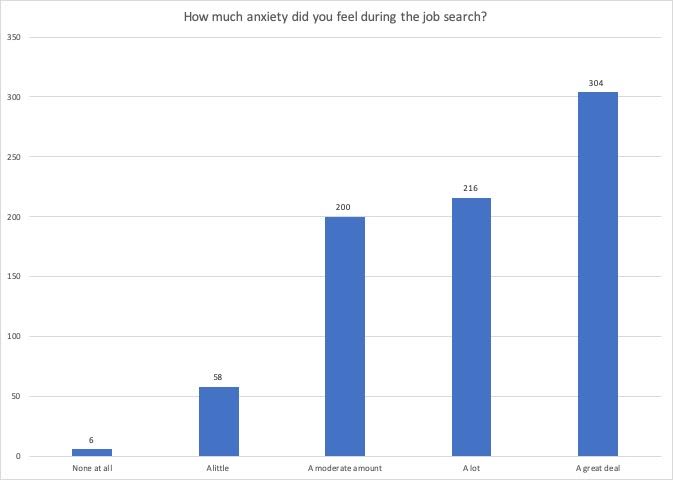

When it came to whether or not respondents felt anxiety during the search, we found overwhelmingly that they did. Three hundred participants responded with “A great deal” when asked to rate their anxiety levels during the search, and over 200 rated it “a lot.” Only 7 respondents stated they felt no anxiety during the search (Figure 1). We did not formally define anxiety in this survey, so participants were able to choose their own definitions for this word. This means that multiple definitions exist, and this influences the findings in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Survey participants in response to: “How much anxiety did you feel during the job search?”.

Full description of Figure 1.

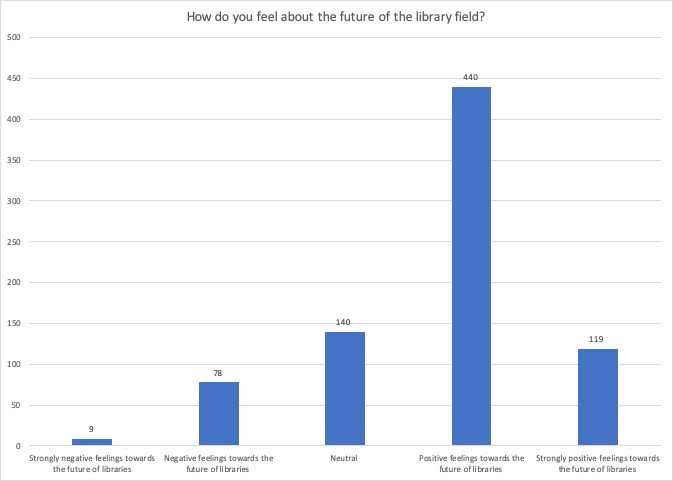

When asked about the future of libraries the response was overwhelmingly positive, with the majority of respondents holding “positive” or “strongly positive” viewpoints (Figure 2). However, when divided amongst those who were employed and those on the job market, the percentages of negative views on the future of librarianship rose for those who were unsuccessful in their search; 12% of unemployed respondents responded negatively compared to 7% of the employed respondents.

Figure 2: Survey participants’ responses to their feelings about the future of the library field.

Full description of Figure 2.

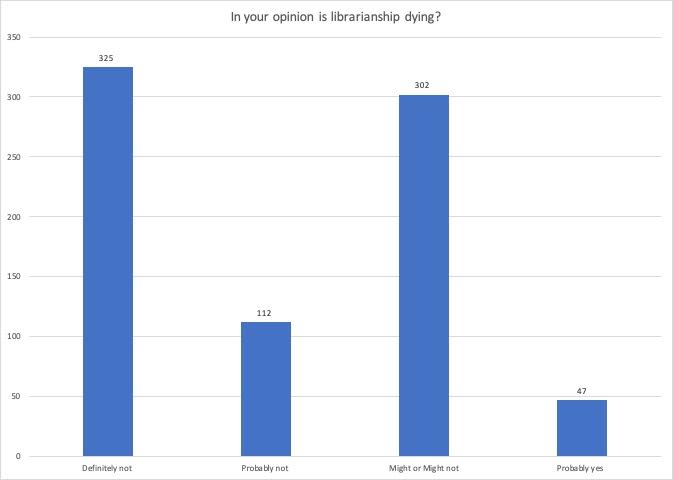

One of the most curious trends in the results above is that despite these narratives of uncertainty and change in libraries, future and current librarians are still hopeful about the future of libraries. Seventy one percent (71%) of respondents reported either “positive feelings about the future of librarianship” or “strongly positive feelings about the future of librarianship” as opposed to only 10% responding in the negative. Consider these numbers when placed within the context of 15% of total respondents having been underemployed and unemployed, searching for a job, or out of the job search. Furthermore, for respondents for whom the job search ended without placement, 54% still held positive views on the future of libraries, which was consistent with the opinions above on the “death of libraries” (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Survey participants’ thoughts on whether librarianship is dying.

Full description of Figure 3.

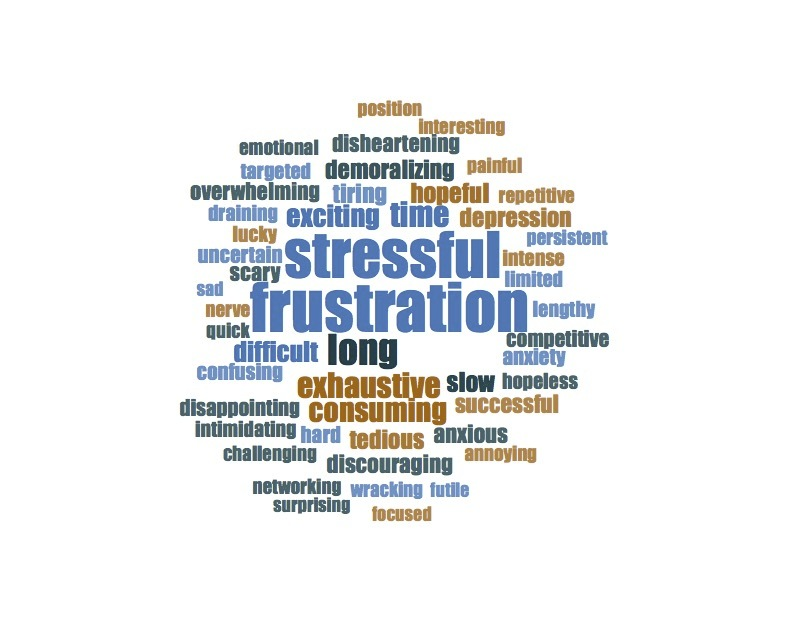

Finally, the question on the survey that yielded particularly interesting results was, “What are three words you would use to describe your job search?” Using Nvivo, we were able to find the words used most frequently (Figure 4). Frustration (and all roots) was the top word used by 177 respondents. Stressful (and all roots) was a close second, with 164 mentions. Long (87), Exhaustive (62), and Time (59) were the top five words chosen.

Figure 4: A visualization created from the free-response of the three words used to describe the job search.

Full description of Figure 4.

In-Depth Interviews

Several important themes permeated our in-depth interviews. Some focused on well-known and well-trodden library research ideas such as resilience in libraries, but others approached ideas around passions and the future of librarianship. One of the themes that has not been talked about much in library research is an intimacy between the job seeker and interviewers and the resulting feelings of rejection afterwards. Each of these confront vulnerable job seekers in striking ways and paint an uncomfortable portrait of what it means to become a librarian post-library school.

“I don’t have to be a librarian” resilience and failure in job searching.

One of the important themes present in our interviews and among our data, was the underlying concept of “resilience” in the face of dwindling odds for facing the competitive job market. One of our respondents, who while a paraprofessional had been on the market for many months for a more stable position, commented that:

…one of the things that I think about a lot, in a lot of talks that I go to, are about resilience. Kind of resilience in libraries, and that’s the kind [of] thing that the word I wish we didn’t have to use as much….. But it takes a lot of fortitude sometimes to get through [the job search]. And if you are new and fresh out of library school… I wish there were more conversations about resilience in that way, as like, ‘Yes. We don’t want you to have to deal with this, but the chances you will are pretty good. Pretty good.’

Yet, because the market is so stressful, we are forced to talk about resilience on the way. Added to this is the expectation that soon job prospects will improve. In fact, one of the persistent myths in librarianship (and indeed most of contemporary employment) is the idea that mass retirements will open the doors to new graduates. One of our interviewees commented:

I always worry that library budgets are being cut, and, you know, people are retiring, which everybody says, ‘Oh everyone, all these librarians are gonna retire and there’s gonna be a million jobs,’ but a lot of those positions aren’t being filled…they’re just sort of being done away with…they have a smaller staff.

Some have attributed this myth to the American Library Association (Hardenbrook 2013; Hiring Librarians Blog 2014) which told students to not be swayed by the dismal employment numbers because retirements were on the way. When these retirements do not materialize, because Americans work longer before retiring, or their positions are replaced by part-time jobs or not replaced at all, the optimism of the graduating student falls.

What persons invested in optimism engage with is an expectation of stability. What we have seen in the recent history of libraries is the exact opposite. This has encouraged many librarians to think of ways to be resilient against inevitable change. One example, from In the Library with the Lead Pipe, explores this in terms of ecological sustainability. Munro writes:

…resilience acknowledges that we live in a state of constant change, in systems that are larger, more complex, and more interrelated than we know. When we try to control change in one part of the system—to optimize it for our current needs—we often create effects that we can’t predict (2011, 2).

For libraries, this comes to the changing formats in collections, the reduction of budgets, and the overall uncertainty that plagues the field’s future (Munro 2011). Resilience is a response to the perpetual uncertainty that confronts libraries, and can, in Munro’s feeling, be overcome with radical cooperation and thoughtful adaptive solutions. Yet this approach does not get at the core of where the resilience narratives harm vulnerable populations.

In recent years, resilience narratives have been pushed back upon. Berg et al. (2018) explain that “demanding resilience in libraries and other contexts helps to conceal larger problems by transferring blame to the individual, resulting in a vicious cycle of the workers in the most precarious positions doing the most work to keep services and collections functioning”. Echoing this sentiment, Meredith Farkas (2017), in a piece for American Libraries, commented that “resilience narratives paint workers who feel burned out or frustrated as failures who couldn’t overcome adversity.” Specifically, these writers are approaching librarian resilience for those who are already within the field, showing the “doing more with less” approaches as difficult for individuals to bear within organizations. Yet, how do resiliency narratives affect those on the job market and those who have given up hope because of the constant uncertainty surrounding librarian futures?

This issue is perhaps exacerbated by the degree itself, and professionalism inherent in its distribution. ((ACRL identifies the MLS as the professional terminal degree required for librarians. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/statementterminal)) The library degree has been painted as the only way into the field. While libraries do not have licensure or certification, the degree itself is one designed for employment purposes and as such is accredited by our associations. When this promise is unfulfilled it is on job seekers to perform the emotional labor of resiliency. One interviewee, a current graduate student on the job search, mentioned their frustration with the MLIS program: “As I’m applying and as I finished my program I was really frustrated with the fact that it felt like all I did was get this golden ticket that meant that I could get some jobs that I had already the skill set for.” Even with this “golden ticket” you are not promised a job that fits your skill set. Another interviewee, who has years of experience in libraries, spoke to the discounting of pre-degree experiences:

So, it was kind of like I needed that degree, but all of the extensive experiences that I had, I 100% feel like that was discounted. Many people have told me, ‘Well, you have to start early career. That’s what you are.’ I was like, ‘That’s not what I am. I’m on year 19 of progressive responsibilities.’

The degree is perceived as essential to permanent stability and the “good life,” and is often sold to students as a “golden ticket” to librarian prosperity. Yet, we know this isn’t true. Factors like experience or geography often interfere with the opportunities presented by the degree.

Passions, Callings, and Co-dependencies

Overwhelmingly, the respondents, even those for whom the job search had ended without a job, were positive about the prospects of the future of the library and of librarianship. Many would still suggest librarianship to students or colleagues as an employment path. For library job seekers who were not successful, this kind of positive attachment is incredibly telling about the cruel state of affairs our field finds itself in. Those who have been promised the librarian “good life” and have yet to achieve it are left in a precarious mental space and are engaged very clearly in a cruel attachment to this field. In some ways, it is partially a result of the ways in which we talk about the sanctity of the library as a space and as a calling, a concept termed “vocational awe” by Fobazi Ettarh (2018).

Noting the religious undertones of vocational thinking, Ettarh comments that librarianship is often talked about as a “calling” and that “the physical space of a library, like its work, has also been seen as a sacred” (2018, 4, 5). The sacred mission of the library and the holiness of its spaces run against our emotional and physical wellbeing as Ettarh poignantly states, “in the face of grand missions of literacy and freedom, advocating for your full lunch break feels petty. And tasked with the responsibility of sustaining democracy and intellectual freedom, taking a mental health day feels shameful” (2018, 11). Perhaps the same is true for job seekers. When called to the profession that holds these high values, it is petty to advocate for the “good life.” In the same way, a person “called” to librarianship, who is attached to librarianship in an optimistic way, and does not reach the “good life,” oftentimes internalizes their failure as not living up to the ideals of the library rather than the cruelty of a vastly diminishing field. The promises and call of librarianship, while noble, are dangerous for the emotional wellbeing of job seekers.

This is, of course, not limited to libraries. On the culture of despair in higher education Pamela Aronson shows that practicality and hireability are a commonality amongst graduates of all stripes, where students are career focused often dropping majors or programs that are passions but not “practical” (Aronson 2018, 395). Aronson’s study found that:

…uncertain plans mirrored the difficult objective work circumstances of recent graduates. Although some interviewees selected what they thought would be ‘recession proof’ majors and/or were able to secure jobs in their field of study after college, about 60 percent were experiencing unemployment, underemployment or malemployment at the time of the interview (2018, 396).

For many, librarianship was a practical approach to a “recession proof” job. A number of our interviewees pointed to practicality as an essential part of a good library program and essential to the job hunt.

When interviewees were prompted about the future of librarianship the conversation quickly turned to “passions” and “excitement” despite the pessimistic undertones of many of the interviews. One interviewee, geographically limited but employed after a six-month search, commented that:

You know, of course, anyone outside of our profession, there’s quite a range of opinions on whether libraries are still useful or not, but if you’re going into this field, hopefully you’re optimistic about it. I can’t imagine going into this field thinking, ‘Oh, yeah, there’s not gonna be anything for me.’ If I had thought that, I would not have continued my program, and I think it definitely, knowing all the cool things that different libraries are doing all the new services that are being offered while there is things you can check out other than books, whether it’s kits, little science kits and things or what the different classes that they’re offering …It made me more excited to be entering the field…

For this interviewee, they had to believe libraries would continue to flourish and provide job opportunities, otherwise it would not have made sense to invest time in gaining the necessary credentials. Yet there is an acknowledgement of the “range of opinions” on the usefulness of libraries in the 21st century. This internal optimism about libraries was not shared among all participants, such as this currently employed librarian working in a special library, stating “I don’t think the library is dead, by any means…. I don’t think it’s necessarily a really solid career choice. And I don’t know if I would have gone and done my MLIS if I had had a clearer picture going in.”

Some of our interviewees felt the pressure from those around them. Another interviewee, a recent graduate who was working part-time at a library while searching for full-time employment, was aware of the articles around the death of libraries, commenting, “[An article about the death of libraries] does not make me feel more optimistic. Yeah, I know that’s what my mom was going for when she sends me these and that’s not how I feel…”

Others, who had stable positions, have difficulty encouraging others to follow the same path into librarianship. One interviewee commented that:

When I do hear that another person applied for the library…wants to be a librarian, like, I’m happy they’re choosing that field. But I’m also thinking, like, there are not enough jobs. And then the jobs that are available usually have, like, 50 applicants for one position. And I can’t be, like, discouraging, obviously. And that’s not to say that I don’t want people to go to library school. But there’s a lot of, like, challenges that come with trying to find a permanent position.

“Weird Rejections,” Auditioning Yourself, and Break Ups

These responses show a deep dedication to and passion for the field of librarianship despite the shifting sands of positivity in the librarianship landscape. Yet, they also illuminate cruel intimacies that play out in the job search process. We return to the work by Sano-Franchini where she comments that

…the concept of cruel optimism can shed light on the ways in which normative ways of desiring on the job search are not only historically and institutionally informed but also function as motivation that enables candidates to persist in a system wherein employment is not always available for all” (emphasis ours) (2016, 104)

Essential here is a deep intimacy within librarianship and job searching which in turn leads to this attachment despite limited hopes of employment.

Throughout our interviews, we saw that within these resilience narratives of applying for job after job, our interviewees also spoke to the intimacy of the job applications they submitted. The reason for this close connection came from advice that your job application materials have to “fit” the job posting, show your knowledge of the field, and your understanding of the institution seeking an employee. As one currently employed academic librarian said about this process:

I feel like you basically have to audition yourself to even get your application looked at. I mean, that’s not really anything new. But I think I definitely felt the pressure of…to make everything perfect…like, for my application, to even…follow-up e-mails. That’s like… And it takes a lot of time, I think, to spend on any other efforts. I mean, you have to do a lot of research on the institution you’re applying for. So, that takes time.

This effort to tailor each application can be intensified as a LIS student, juggling coursework, work, and job applications. One of our interviewees, a graduate student seeking academic librarianship jobs, mentioned this about the application process:

And definitely how rigorous the application process or the job application process has become, definitely has caused me some burnout. There are some weeks where I know that I should be trying for these things, but if I’ve already filled out 20 applications and 20 cover letters, I’m tired.

Recall, from above, conversations surrounding “fit” in library job searches, fit is itself a performance of intimacy on the part of the employer investigating whether or not the person interviewing fits into the narrow spectrum of the library without truly understanding the complexities of individuals and institutions. A “tailored cover letter,” for instance, is a “performance of intimacy that is oftentimes desired, if not expected, by institutional agents (search committees)” (Sano-Franchini 2016, 108). Not only is intimacy required by institutions, intimacies appear within our interviews in terms of cohorts, mentors, or schools. So, what does this mean for the job search and anxiety?

Any kind of intimacy is an attachment, and the attachment here is to the difficult field of librarianship. It relies in some ways on the calling aspects of vocational awe. For those who do not make it into the field after a year or two of searching, failure might not, as our data shows, change their opinion of librarianship as a whole but it does harm to their ability to see themselves as anything other than failures. Pushing the metaphor of intimacy into the realm of romantic relationships, rejection feels to job searchers like a breakup and their repeated attempts at new connections feel like desperation because they feel “punished when they reach out and the beloved is curt” (Sano-Franchini 2016, 116). One of our interviewees, a part-time librarian seeking full-time employment, stated:

I’ve had a lot of really weird rejections, or unofficial rejections, where they just never respond after a phone interview, or a Skype interview. And not responding to a paper application, I mean that’s not great, but it’s par for the course. But not responding… Not officially rejecting someone after you’ve actually talked to them feels really rude to me.

We often would not think of large institutions as being capable of rudeness, but the job search relies on an intimacy that allows rudeness to be “par for the course.” This respondent felt intimacy through the interview process, through the materials they specifically created and the connections formed through the interview. When they did not receive a response or were not selected, they felt unfairly treated.

These breakups go so badly that pure frustration makes some librarian hopefuls leave librarianship. As one interviewee, currently in a temporary library position after a year and a half of searching, said:

And I, I need a little more focus or help to get to see what else is out there. Because I, I have skills I want to use. I really like being a librarian. But I don’t have to have, to be a librarian, you know? I want to do something I’m excited about. And I want to do something that matters and pays the bills. But, I’m, I’m pretty open-minded too.

The field has asked resilience for this particular candidate who wants to be a librarian, likes librarianship, and has skills and a passion to share. MLS degree holders are sometimes forced to move on with their lives, similar to the individual who comes to the end of a romantic relationship.

Conclusion and a Call to Action

For those who have been successful in the job search, many point to luck as a factor because success feels so fleeting in our field. While we acknowledge the difficulties surrounding the search and the prospects for new job seekers, it is difficult to offer real solutions to this ongoing situation. The attachments we form to librarianship are inherently cruel as long as we, as a field, as LIS programs, ALA, and as employers of librarians, continue to promise a job at the end of graduation and cannot fulfill that promise. For those under or precariously employed or unemployed colleagues it means very little to ask for resilience in this time. Job seekers are expected to be dedicated to and passionate about the field, while also intimately aware of individual libraries and systems. We encourage them to consider it a calling more than a simple job to assuage fears that they might not be lucky enough to find stable employment. It is not our intention to demonize the system in which we are deeply embedded, but our hope is that our study can provide some illumination of the difficulties for new job seekers in librarianship. What we learned throughout this research is that more work needs to be done around the LIS job search. This project was a small step in uncovering the various ways our newest colleagues seek out employment. As one of our academic librarian interviewees said, “just acknowledging that searching for jobs can really suck” can be important. While we were fortunate, it is essential that we remember that many of our friends were and are not.

So, what can be done? We believe that it is essential that library programs, librarians and administrators involved in hiring, and future library students be aware of the difficult emotions surrounding the job search. Those of us with secure employment must work to lift those without up as best we can. This support can come through mentorship (both formal and informal), in advocacy, and in the ways in which we conduct hiring. It is also the responsibility of library schools to provide the necessary tools and experiences for job placement at graduation. Is the MLS degree enough, in its current state, enough for gainful employment? For those respondents and colleagues who are struggling to find the good life, the answer is no. There is an implicit (and oftentimes explicit) promise that the MLS will lead to a library job at the end of the program. If this is not the case, as we learned from our data, there needs to be a change in the way that programs are marketed, administered, and the support given to graduating students and new graduates. When a student leaves library school it becomes the responsibility of the library community as a whole to guide these new colleagues onto the path of gainful employment. Neoliberalism, which fosters ongoing austerity movements in the public sector and the systematic defunding and devaluing of libraries, pits us against each other and help is not often in its vocabulary. As a result, the community has, oftentimes, failed in this regard for these job seekers and we must as a whole do better.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank everyone who filled out survey, those we interviewed, and those who have talked to us about their job search while we have worked on this project. Without your perspectives, this paper would not exist.

We would also like to thank our In the Library with the Lead Pipe collaborators — Ian Beilin and Bethany Radcliffe — as well as our external reviewer, Eamon Tewell. Your insight and comments have helped to make this a stronger paper.

Works Cited

Allard, Suzie. 2017. “Placements & Salaries 2017: Librarians Everywhere.” Library Journal Placements & Salaries. Library Journal. https://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=librarians-everywhere.

Anonymous. 2014. “Don’t Believe the Myth about the Large Number of Librarians Retiring and the Impending Librarian Shortage.” Hiring Librarians. December 2014. https://hiringlibrarians.com/2014/12/28/dont-believe-the-myth-about-the-large-number-of-librarians-retiring-and-the-impending-librarian-shortage/.

Aronson, Pamela. 2017. “Contradictions in the American Dream: High Educational and Perceptions of Deteriorating Institutional.” International Journal of Psychology 52 (1): 49–57.

———. 2018. “‘I’ve Learned to Love What’s to Pay Me’: A Culture of Despair in Higher Education during a Time of Insecurity.” Critical Sociology 43 (3): 389–403.

Berg, Jacob, Angela Galvan, and Eamon Tewell. 2018. “Responding to and Reimagining Resilience in Academic Libraries.” The Journal of New Librarianship 3 (1): 1–4.

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Cunningham, Sojourna, Samantha Guss, and Jennifer Stout. 2019. “Challenging the ‘Good Fit’ Narrative: Creating Inclusive Recruitment in Academic Libraries.” In Recasting the Narrative: The Proceedings of the ACRL 2019 Conference. Cleveland, Ohio.

Eckard, Max, Ashley Rosener, and Lindy Scripps-Hoekstra. 2014. “Factors That Increase the Probability of a Successful Academic Library Job Search.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 40 (2): 107–15.

Ettarh, Fobazi. 2018. “Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2018/vocational-awe/

Farkas, Meredith. 2015. “The Insidious Nature of ‘Fit’ in Hiring and the Workplace.” Information Wants to Be Free. 2015. https://meredith.wolfwater.com/wordpress/2015/09/28/the-insidious-nature-of-fit-in-hiring/.

———. 2017. “Less Is Not More Resilience Narratives for Library Workers.” American Libraries, 2017. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2017/11/01/resilience-less-is-not-more/.

———. 2019. “Is ‘Fit’ a Bad Fit?” American Libraries, June 3, 2019. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2019/06/03/cultural-fit-bad-fit/.

Galvan, Angela. 2015. “Soliciting Performance, Hiding Bias: Whiteness and Librarianship.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/soliciting-performance-hiding-bias-whiteness-and-librarianship/.

Grady, Jenifer. 2009. “Answering the Calls of ‘What’s Next’ and ‘Library Workers Cannot Live by Love Alone’ through Certification and Salary Research.” Library Trends 58 (2): 229–45.

Hardenbrook, Joe. 2013. “The Librarian Shortage Myth & Blaming Library School.” Mr. Library Dude. July 2013. https://mrlibrarydude.wordpress.com/2013/07/05/the-librarian-shortage-myth-blaming-library-school/.

Hathcock, April. 2015. “White Librarianship in Blackface: Diversity Initiatives in LIS.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/lis-diversity/.

Kim, Kyung-Sun, and Sei-Ching Joanna Sin. 2008. “Increasing Ethnic Diversity in LIS: Strategies Suggested by Librarians of Color.” The Library Quarterly 78 (2): 153–77.

Lacy, Megan, and Andrea J. Copeland. 2013. “The Role of Mentorship Programs in LIS Education and in Professional Development.” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 54 (2): 135–46.

Moore, Alex, and Matthew Clarke. 2016. “‘Cruel Optimism’: Teacher Attachment to Professionalism in an Era of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (5): 666–77.

Morgan, Jennifer Craft, Brandy Farrar, and Irene Owens. 2009. “Documenting Diversity among Working LIS Graduates.” Library Trends 58 (2): 192–214.

Munro, Karen. 2011. “Resilience vs. Sustainability: The Future of Libraries.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2011/resilience-vs-sustainability-the-future-of-libraries/.

“Occupational Outlook Handbook, Librarians.” 2016. Washington D.C: Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor.

Roy, Loriene, Trina Bolfing, and Bonnie Bzozowski. 2010. “Computer Classes for Job Seekers: LIS Students Team with Public Librarians to Extend Public Services.” Public Library Quarterly 29 (3): 193–209.

Sano-Franchini, Jennifer. 2016. “‘It’s Like Writing Yourself into a Codependent with Someone Who Doesn’t Want You!’ Emotional Labor, Intimacy, and the Academic Job Market in Rhetoric and Composition.” College Composition and Communication 68 (1): 98–124.

Tewell, Eamon. 2012. “Employment Opportunities for New Academic Librarians: Assessing the Availability of Entry Level Jobs.” Portal: Libraries and the Academy 12 (4): 407–423.

Vinopal, Jennifer. 2016. “The Quest for Diversity in Library Staffing: From Awareness to Action.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/quest-for-diversity.

Appendix A: In-depth Interview Questions

- For your most recent job search, how long were you on the job search market?

- Can you describe how you went about finding a job? What resources (materials or people) did you rely on? Did you come up with any strategies or borrow from others?

- What did you feel were your biggest challenges during the search?

- What were some defining moments during your search?

- How do you feel about the future of the library field, and did that influence your job search?

- Do you believe your MLS program prepared you for the job search? Why or why not? In what ways do you feel your MLS program prepared you (or did not prepare you) for the job search?

- Did any of your relationships or friendships with your peers/colleagues change during the job search? If they did change, why do you think that happened?

- Is there any advice you’d give prospective applicants on their job search?

- Is there anything else about your job search you’d like to share with us today?

Appendix B: Figure Descriptions

Full Description of Figure 1

Survey participants in response to: “How much anxiety did you feel during the job search?”

Level of anxiety, Number of respondents

- A great deal, 305

- A lot, 217

- A moderate amount, 201

- A little, 59

- None at all, 7

Full Description of Figure 2

Survey participants’ responses to their feelings about the future of the library field

Feelings, Number of respondents

- Strongly positive feelings towards the future of libraries, 120

- Positive feelings towards the future of libraries, 441

- Neutral, 140

- Negative feelings towards the future of libraries, 79

- Strongly negative feelings towards the future of libraries, 10

Full Description of Figure 3

Survey participants’ thoughts on whether librarianship is dying

Feelings, Number of respondents

- Definitely no, 325

- Probably not, 112

- Might or Might not, 302

- Probably Yes, 47

- Definitely Yes, 10

Full Description of Figure 4

List of the 100 most frequent free-response words used by survey respondents to describe their job search

Word, Number of responses

- frustrating, 172

- stressful, 163

- long, 87

- exhausting, 59

- time, 58

- consuming, 51

- exciting, 43

- difficult, 36

- slow, 34

- demoralizing, 31

- tedious, 31

- hopeful, 30

- tiring, 28

- depressing, 27

- anxious, 26

- discouraging, 26

- successful, 25

- disheartening, 24

- overwhelming, 21

- scary, 21

- anxiety, 20

- competitive, 18

- confusing, 18

- disappointing, 18

- hard, 18

- uncertain, 17

- limited, 16

- hopeless, 15

- lucky, 14

- targeted, 14

- draining, 13

- intimidating, 13

- lengthy, 13

- challenging, 11

- nerve, 11

- painful, 11

- quick, 11

- wracking, 11

- annoying, 10

- intense, 10

- interesting, 10

- repetitive, 9

- futile, 8

- sad, 8

- arduous, 7

- constant, 7

- daunting, 7

- emotional, 7

- extensive, 7

- fruitless, 7

- networking, 7

- persistent, 7

- unsure, 7

- complex, 6

- defeating, 6

- desperate, 6

- educational, 6

- focused, 6

- inducing, 6

- ongoing, 6

- serendipitous, 6

- surprising, 6

- thorough, 6

- uncertainty, 6

- determined, 5

- drawn, 5

- easy, 5

- fast, 5

- fortunate, 5

- frightening, 5

- impossible, 5

- job, 5

- library, 5

- local, 5

- methodical, 5

- nervous, 5

- optimistic, 5

- organized, 5

- pessimistic, 5

- position, 5

- scarce, 5

- selective, 5

- self, 5

- wide, 5

- arbitrary, 4

- brief, 4

- casual, 4

- complicated, 4

- ending, 4

- expensive, 4

- full, 4

- intensive, 4

- intermittent, 4

- luck, 4

- monotonous, 4

- never, 4

- patience, 4

- positive, 4

- prolonged, 4

- short, 4

Pingback : Happenings – VREPS

I’m glad I have a job in IT.

Pingback : LITA Job Board Analysis Report – Laura Costello (Chair, Assessment & Research) LITA Assessment & Research and Diversity & Inclusion Committees – LITA Blog