Consultants in Canadian Academic Libraries: Adding New Voices to the Story

In Brief

The practice of hiring consultants in academic libraries is widespread, but research on the topic is not. We argue that this practice stems from underlying neoliberal ideals that may disenfranchise library workers. This research is the first to include the experiences and perspectives of library employees to better understand the practice of hiring consultants in academic libraries. We surveyed 189 library employees from English language Canadian universities and colleges about their experiences and perceptions of consultant use in their libraries. Participants were assigned to either library administrator (n=21) or library worker (n=168) employee groups and were asked to provide insight into their experiences with consultants. Pivot tables were used to examine descriptive statistics and compare groups of respondents. The qualitative data was examined using a theoretical thematic analysis to address three themes: motivations for hiring consultants, the impact of the practice on library work and workplace culture, and perceptions of consultant work. We discuss these three themes by unpacking the role that power plays with respect to this practice. We find that the practice of hiring consultants is indeed a trend in Canadian academic libraries, but that both groups of participants are conflicted about the impact of the practice.

Introduction

The practice of hiring consultants in Canadian academic libraries appears to be a growing trend (Harrington & Dymarz, 2018). However, scholarly research on the topic has not grown with it. In this way, consultant use is similar to other practices in academic libraries that have become commonplace and often go unexamined, including strategic planning initiatives, the deskilling and downsizing of librarian labour, and private sector relationships in libraries (Adler, 2015). Practices such as these that gradually seep into an organization without critical analyses or examination become normative. We believe that critically engaging with these practices can reveal underlying and unacknowledged forces within our workplaces that directly shape the nature of individuals’ work and library workplace culture.

In 2018, we conducted a historical review of the literature about consultants in libraries to document the origin and scope of this practice. We also analyzed Library and Information Science (LIS) texts to show how students studying librarianship, and hence future librarians, learn about consultants. Three common tenets were repeated throughout LIS texts: consultants are “unbiased”, they provide “expertise”, and they offer “fresh ideas”. We also identified rhetorical strategies that appear throughout these texts, including the use of figurative and indirect language used to describe consultants’ roles. We concluded that the linguistic strategies used when characterizing consultants blur the reality of the practice, rather than clarify the role of consultants in libraries. Our historical review outlined the growth and development of the practice of hiring consultants in libraries, and our textual analysis critiqued common representations of consultants and problematized the existing discourse within the library literature.

The linguistic strategies identified in these texts also demonstrate how knowledge and power are exerted through the language employed about consultants. Knowledge and power are observed to be interwoven concepts in a consulting relationship (Pozzebon, 2012). We considered how knowledge and power play out in library settings when consultants are hired as experts and are given authority and control to make decisions about library work, decisions that affect the day-to-day work of library employees. Disturbingly, we found that the literature and texts rarely include the perspective of library workers or address the impact of practices such as consulting on their work. We framed the practice of hiring consultants in academic libraries as a neoliberal practice that impacts the agency of library employees through mechanisms of knowledge and power.

To address the lack of voices of library workers on the ground, our current research examines the experiences of library employees whose labour may be affected by the practice of hiring consultants. 189 library employees from English language Canadian universities and colleges were surveyed about their past experiences and current perceptions of consultant use in their libraries. Participants were assigned to either library administrator (n=21) or library worker (n=168) employee groups and asked to provide insight into their experiences with consultants, the impact on their work and workplace culture, and their understanding of consultants’ work in their libraries.

In this article, we first define and clarify frequently-used terms, then follow with a short review of the practice of hiring consultants in libraries. We incorporate an introduction to research about Canadian academic libraries to situate our findings into the context of academic library workers in Canada. Next, we present our survey methodology and highlight the quantitative results. The discussion section further explores our research questions addressing how themes of power play out in organizational hierarchies for individuals working in academic libraries in neoliberal times. The qualitative results from open-ended survey questions are woven into the discussion section. Our conclusion reaffirms the importance of objectively examining the political and economic contexts in which academic libraries operate.

Literature Review

Definitions and themes of power

Several terms and themes that are central in our article need to be defined and introduced. In our work, library consultant is defined as “an individual offering a range of professional skills and advice relevant to the operation of libraries. Usually these skills will be marketed on a commercial basis by a […] person who is not directly employed by the library concerned but retained on contract for a fee” (Prytherch, 2005). We use the phrase “the practice” throughout this article to capture the work for which a consultant is hired.

Next, themes of power connected to neoliberalism, organizational hierarchy, and agency are introduced, then further examined in relation to our findings in the discussion section.

To begin, we believe that academic libraries are affected by the neoliberal ideologies that support private sector control, ongoing efficiencies, accountabilities, and austerity measures of doing more with less (Bousquet, 2008). Furthermore, we consider consulting to be a neoliberal practice that addresses crises and change by using corporate solutions. Arguably, the interaction between corporate solutions and work in public institutions can be incongruent. For example, using corporate solutions for strategic planning, staff restructuring, and other organizational change may create conflict between the values of the profession (American Library Association, 2019) and the consultant’s work and recommendations for the library. Seale (2013) highlights a possible conflict between hiring ALA consultants to define and measure value in academic libraries when these consultants are also LIS scholars. Consultants, and in this case ALA consultants, may not have a critical distance from their own work creating “a closed discursive system that undoubtedly promotes the uncritical adoption of ideas that seem authoritative and obvious” (p. 54). Explicit conversations and engagement with a seemingly benign practice like hiring consultants exposes the unacknowledged impact of neoliberal practices on library employees’ work and workplace culture. We acknowledge the need to accept that librarianship is embedded in neoliberal political and economic contexts, as well as the need to recognize and discuss these contexts to create alternatives (Seale, 2013).

We also acknowledge that while organizational hierarchies are not solely a function of neoliberal structures, they are connected to power. In her research about library organization and management, Lynch (1979) describes libraries as highly bureaucratic institutions that account for ongoing and eternal hierarchical structures in libraries. Systemically, administrative power becomes built into organizational hierarchy with the greatest control, power and autonomy at the top, and control, power and autonomy decreasing as you move down the hierarchy. Ongoing neoliberal ideals which espouse “performance-, cost-, efficiency- and audit-oriented” practices have been introduced into not-for-profit organizations such as those in higher education (Diefenbach & Sillince, 2011, p.1522). These institutions then become progressively bureaucratic, and neoliberal practices become synonymous with an increase in organizational hierarchy, with “increasing numbers of hierarchical levels providing people with disproportionate privileges and opportunities as well as unequal working conditions” (Diefenbach & Sillince, 2011p.1522).

And finally, we introduce the theme of agency to explore both the empowering and disempowering aspects of the practice on the individual and the workplace. We use agency to describe the power an individual may or may not exercise as a result of the practice of hiring consultants. Eggertsson (1990) states that a consultant will always have a strategic advantage as a consulting relationship can never be balanced. Furthermore, in a discussion of power and politics in organizational studies, Blackler (2011) conceptualizes power in four quadrants differentiating between personal power and collective power and between overt and unobtrusive power. Our use of agency focuses on personal power in the overt sense (for example: having expertise, valued information, or connections). The remaining literature review uses and unpacks these definitions and themes in relation to the practice of hiring consultants in a Canadian context.

The Canadian context

The goal of our current research is to include the voices of Canadian academic library employees when considering the practice of hiring consultants. Because universities and colleges are major academic institutions in Canada, but there is little research on college libraries (Arnold, 2010), we targeted library employees from both Canadian colleges and universities.

In addition, minimal research exists that includes Canadian academic library employees as a group. The most significant research would be the Future of Human Resources in Canadian Libraries published in 2005 (Ingles). This study conducted interviews, focus groups and surveys with four types of staff (librarians, other professionals, support staff, and paraprofessionals) across a variety of libraries (special, school, academic, and public) to investigate human resource challenges facing libraries in Canada. The authors presented their findings in terms of 8Rs: recruitment, retirement, retention, rejuvenation, repatriation, re-accreditation, remuneration, and restructuring.

In response to the 8Rs study, the Canadian Association of Research Libraries (CARL) published 8Rs Redux in 2015 (DeLong, Sorensen & Williamson). This research also surveyed four staffing groups (librarians, other professionals, support staff, and paraprofessionals) to investigate changes in human resource challenges and to extrapolate for future planning. However, this is not a representative study because CARL includes 29 research libraries in Canada, while other university libraries and all college libraries were excluded. Findings from this study indicate that organizational change will continue in academic libraries due to transformations of postsecondary education in Canada, declining budgets, impact of new technologies, and capacity of current staff. The 8Rs Redux study highlights barriers to organizational change that include organizational culture, staff who are resistant to change, lack of employee involvement in change, and organizational hierarchical structure (p. X). Borrowing directly from corporate ideologies, the report states that the “literature on organizational change and development provides evidence that principles of organizational development can be used within higher education to address the underlying causes of organizational problems while still maintaining commitment to academic excellence.” (p. X) Because library consultants are commonly hired for strategic human resources planning, such as organizational change, this study is relevant to our own work.

Consulting in libraries

The practice of hiring consultants originated in private, for-profit sectors where it developed quickly and without independent research to substantiate its use. Fincham and Clark (2002) for example, highlight how the lack of research about consultants in management has “constrained and distorted” what the practice is about.

According to Fincham and Clark (2002), two distinct themes emerge in the literature written about management consultants: an organizational development perspective and a critical perspective. The organizational development literature is more common and is preoccupied with improving efficacy, consultants’ success, and the role of the consultant from the consultants’ point-of-view (Appelbaum & Steed, 2005; Kakabadse, Kakabadse & Louchart, 2006). In contrast, the critical perspective “is regarded as a type of social discourse the elements of which reflect issues of power and the construction of knowledge” (Fincham & Clark, 2002). Literature with a critical perspective serves to critique the practice of consulting as opposed to simply improving its efficacy or scope without question.

Scale (2016) found that there is minimal academic research, critical or supportive, about consultants in any type of library. The literature that is available primarily presents an organizational development perspective. For example, the professional literature centers on organizational and operational questions including how to hire a good consultant (Matthews, 1994), how to be a good consultant (Wormell, Olesen & Mikulás, 2011), and the factors that lead to successful consultant experiences (Garten, 1992). This work begins and ends with the premise that the practice of hiring consultants is advantageous, and it precludes the need to ask further questions. In Matthews’ report on the effective use of consultants in libraries, the role of the consultant is not questioned. Consultant expertise is assumed throughout the report, but never discussed. Similarly, there are texts written by consultants about their work, often for other consultants or those who aspire to this practice (see: de Stricker, 2008, 2010; Skrzeszewski, 2006; and the LIS publication of the Association of Independent Information Professionals: AIIP Connections).

We discussed a perceived trend in academic libraries to hire consultants for internal crises, change management projects, strategic planning processes and more (Harrington & Dymarz, 2018). Our literature review summarized work written about consultants in libraries and we used this review to document a chronological history of the practice. The trajectory of the practice was on a continuum, beginning with construction and survey work (1940-60), moving to service and operational changes (1970-80), then on to environmental changes and budget challenges (1990-2000), and today reflecting organizational changes and change management (2010-present). We found that consulting originated from private, corporate models without consideration of its fit for libraries as public organizations, revealing an imbalance between the growth of the practice in the field and the literature available about it. For example, private sector approaches were readily adopted in libraries. In an entry in the 1975 edition of the Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Schell recommends that LIS should bring basic theory and practice from business consulting and apply it directly to libraries, while also acknowledging that there is little written about consulting in libraries.

We then examined what was written about consultants in the review literature as well as LIS educational materials from the library collection of a long-standing, ALA-accredited LIS program (Harrington & Dymarz 2018). The list of titles was generated from derivations of “library consultant” using keyword and subject heading searches. Dictionaries, encyclopedias, directories, handbooks, guides, professional and scholarly publications were examined for the types of language used to define and characterize consultants over time. Our findings indicate that the organizational development perspective is replicated throughout these texts. The hiring of consultants, and the language used to describe their role have not been challenged. For example, we found three core tenets used to describe library consultants: library consultants are “unbiased” professionals, who bring “expertise” and “fresh ideas” to a library. Over time, characterizations and definitions of library consultants transformed from a description of consultant as “specialist” in 1943 (Thompson) to consultant as “expert” by the 1980’s (Young & Belanger). Consultants also were defined by their “fresh ideas” beginning in 1969 (Berry) and extending at least to 2011 (Wormell). Consultants were characterized as “unbiased” beginning in 1977 (Lockwood). We argued that this transformation was due to the restatement of representations of consultants over time, without examination or evidence of their accuracy. We also suggested that repeating these consultant characteristics over time not only regularized the practice of hiring consultants as unbiased experts with fresh ideas but could also have disempowered library workers.

The second focus of our (2018) textual analysis found an overuse of rhetorical strategies, including polarizing, figurative and indirect language. Polarizing language can be hostile and normalizes extremes of positive and negative characterizations of consultants. Polarizing language does not leave room for informed nuanced or critical discussion about the evidence, value or outcome of the practice. For example, champions portray consultants as innovative, forward-thinking, and transformational (de Stricker, 2010). In contrast, the opposing side claims that consultants “waste time, cost money, demoralize and distract your best people, and don’t solve problems” (Townsend, 1970 p. 68). Figurative and indirect language is often used to describe the work of consultants. This includes timekeeper, monitor, talisman, advocate, parasite, gardener, pilot, guide, trouble shooter, ritual pig, and magician (Robbins-Carter, 1984; Kakabadse, Kakabadse & Louchart, 2006) Rhetorical strategies such as these are intended to persuade a reader to accept the author’s characterization of the consultants, but they do not clarify the consultant’s role.

Although neoliberalism and agency are two themes that emerged from our historical review and textual analysis, it was necessary to investigate whether other themes might also emerge by surveying the experiences of the people involved with consultants in their libraries. The present research thus serves as a further step to shift the discourse towards a more critically informed perspective when examining the role of consultants by addressing the following research questions:

- What are the perceived motivations for hiring consultants in academic libraries?

- What is the impact of hiring consultants on library employees and workplace culture?

- What are the perceptions around consultants and consultant use by library employees?

Building on our previous research, we use descriptions and characteristics of consultants documented in the literature, along with themes of power, to investigate experiences and perceptions of Canadian academic library employees.

Method

Using online survey software from Fluid Surveys, we developed 31 multiple-choice, closed-, and open-ended questions focussing on participants’ experiences with consultants during the past five years. Five open-ended qualitative questions provided space for respondents to write about their perceptions and experiences with consultants that may not have been captured in the closed-ended questions. Additionally, five multiple-choice questions included an open-ended “other” option, with the space to provide specific information. We received 260 surveys and analyzed 189. Surveys were excluded if they were less than 35% complete, if respondents did not work in a Canadian academic library, or if they did not work full-time.

The content of the questions was generated from background reading about the role of consultants in libraries, and more specifically as a result of our previous research on consultants in libraries. For example, the types of consulting work that were most prevalent in the literature were highlighted in question 3, where respondents were asked to “Select all areas of focus that consultants have worked on in your library.” Similarly, we asked for levels of agreement across themes (questions 5-7, 17) that were replicated throughout texts about consultants: consultants are part of internal, organizational change; they provide expertise, objective advice, and fresh ideas; and consultants are essential. These survey questions can be regarded as the start of a dialogue that continued into the open-ended “further comments” sections. A small amount of demographic data was collected using multiple-choice options, including the province or territory where employed, type of academic institution (primarily undergraduate, comprehensive, medical / doctoral), years of experience in academic libraries, education level, and union representation. We did not collect racial or ethnic data. For anonymity purposes, we did not collect any identifying information such as name, email, or name of institution. The full survey is included in Appendix B.

During fall 2017, we recruited library employees working at English language colleges and universities in Canada to participate. Specifically, we targeted two groups of respondents: library administrators and library workers (referred to in the aggregate as library employees). Library workers include the roles of library assistants, librarians, department or division heads, or other professionals working in the library. Library administrators are university librarians, chief librarians, deans of libraries, associate university librarians, associate deans of libraries, or executive directors of libraries. These groups were established to ensure that we had a variety of perspectives about consultant use, from those that hired the consultants (library administration) to those that carried out the consultants’ recommendations (library workers).

Participants in the library administrator group were recruited originally through a list from the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. Library administrators were invited to participate and to circulate our call for participants within their libraries. We thought that this was a good recruitment method to ensure that all library employees could be given the opportunity to participate. That is, although there are many professional organizations and list-serves available to reach Canadian academic librarians, reaching other library staff is more challenging. However, we received feedback from one university librarian who suggested that this solicitation would work for administrators, but it would be rare for administrators to forward a solicitation email on to their staff due to the time and effort it would take to vet the appropriateness of the study. Because of this feedback, we revised our recruitment method. We began to recruit participants using national (e.g. Canadian Association of Professional Academic Librarians, CAPAL) and provincial (e.g. British Columbia Library Association, BCLA; jerome-l, Alberta; Ontario College and University Library Association, OCULA) Canadian academic library listservs to expand the reach of our call for participation.

Descriptive statistics were calculated to categorize perceptions and experiences with library consultants across the two respondent groups. Pivot tables were used to analyze descriptive statistics and compare groups of respondents. Qualitative analysis was conducted using themes derived from our previous research and further identified in our survey questions. After a rigorous reading of the written responses by both researchers, the qualitative data were hand coded for emerging themes that were not previously identified.

Throughout the Findings and Discussion sections, we provide quotes from both employee groups. For anonymity, each respondent has been given a pseudonym, and identified by their employee group. We did not provide job type because this could identify the respondent. In total, we include quotes from 26 library employees with 14 representing librarian voices, and the remainder representing administrators and library workers who did not identify as librarians.

Findings

We report our findings by collapsing the questions from the survey questions into three sections. After describing respondent demographics, we move on to topics about experience with consultants, then to perceived impact and value of consultants. The qualitative results from open-ended survey questions are incorporated into the discussion section.

Demographic Information

Demographic information was collected in order to situate the respondents in groups and academic affiliations. The library worker group, with 168 respondents, also included four responses from library workers who are affiliated with Canadian consortial groups. This was considered an appropriate placement because these respondents also stated that they were affiliated with academic libraries or institutions. The library administrator group included 21 respondents. College employees represent approximately 10% of each group. Table 1 represents the group and academic affiliation of all respondents.

| College | University | Consortium | Total (189) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrators | 10% (2) | 90% (19) | – | 11% (21) |

| Library workers | 11% (18) | 87% (146) | 2% (4) | 89% (168) |

Full equivalent of this table as a list.

We received responses from all ten Canadian provinces. As Table 2 illustrates, the representation from British Columbia and Ontario is the strongest. For purposes of confidentiality, we did not ask respondents to identify their institution. Therefore, responses cannot be grouped any more precisely than by province. However, there could be overlap in institution amongst any of the participants. Ten participants did not answer this question.

Survey questions 20 to 28 collected information to further describe those who responded to the survey. Eighty-one percent of the library employee respondents are governed by a collective agreement, and over half (55%) identified as a librarian when asked to indicate their job type. Additionally, 74% of library workers and 95% of administrators identified as having at least an MLIS, MLS, or equivalent. Half (50%) of the library workers have been employed in libraries less than 10 years, while just over half (55%) of library administrators have worked in libraries for over 21 years. Thirty percent of respondents worked in primarily undergraduate institutions, 43% in comprehensive universities, and 17% in medical/doctoral universities. In terms of the size of the institution as defined by the number of full-time equivalent students, 38% of respondents work at institutions with fewer than 12,000 students, 23% lay between 12,000-24,000 students, and 40% are employed at institutions with over 24,000 students.

| Geographic location | Administrators (21) |

Library workers (158) |

|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 9 | 49 |

| Alberta | 0 | 20 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 | 0 |

| Manitoba | 0 | 8 |

| Ontario | 8 | 58 |

| Québec | 1 | 7 |

| New Brunswick | 1 | 1 |

| Nova Scotia | 1 | 11 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0 | 1 |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 0 | 3 |

Full equivalent of this table as a list

Experiences with consultants

When we explored experiences with consultants, 62% of administrators and 64% of library workers reported that their library had hired a consultant in the past. Thirty-eight percent of administrators were involved with hiring a consultant, compared with 13% of the library workers. With respect to the consultation process itself, 80% of administrators reported that they were active participants in contrast to 64% of the library workers. These responses are presented in Table 3.

| Employee Group | Q1: My library has hired a consultant in the past (189) | Q11: I was involved in the hiring process (120) | Q12: I participated in the consultation process (120) | Q30: I have worked as a consultant in the past (186) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrators (21) | Yes | 62% (13) | Yes | 38% (5) | Yes | 80% (10) | Yes | 30% (6) |

| No | 24% (5) | No | 62% (8) | No | 20% (3) | No | 70% (14) | |

| Unsure | 14% (3) | |||||||

| Library workers (168) | Yes | 64% (108) | Yes | 13% (14) | Yes | 64% (68) | Yes | 6% (10) |

| No | 14% (23) | No | 87% (93) | No | 36% (39) | No | 94% (156) | |

| Unsure | 22% (37) | |||||||

Full equivalent of this table as a list

If a respondent indicated that a consultant had not worked in their library, they were asked to choose all that applied to their experience from a predetermined list or add their own reasons concerning why they believed this was so. Of the 17% of respondents who completed this question (n=32), there was a response count of 61. More than half (53%) chose the statement: “it is not common practice at my library to hire consultants.” The second most frequent response was “it is too expensive” (44%), and the third was “we rely on internal expertise” (25%). In contrast, 79% of respondents (n=150) who have had consultants work in their libraries were asked to choose the most common reasons for hiring a consultant. Again, they could choose all that applied to their experience from the predetermined list or add their own reasons, resulting in a response count of 426. The most frequent reason was “to provide guidance for decision making” with 65% (n=97), followed closely by “to complete a project that requires skills or knowledge not currently held by library employees” with 63% (n=94), and with just below half (49%, n=73) choosing “to lend external credence to a course of action”. Four percent of the respondents did not answer either of these questions.

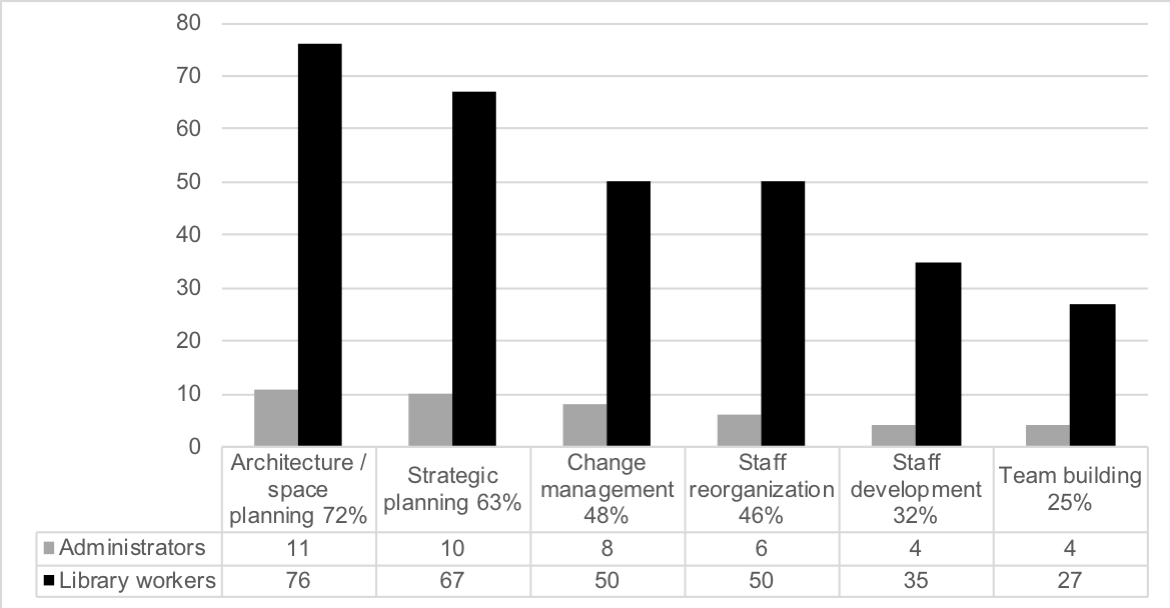

122 respondents across the two employee groups identified the focus of consultant work in their libraries (see Figure 1). Architecture and space planning was identified as the most common reason consultants are hired, and unquestionably requires specialized professionals. The other areas of focus that followed were categorized into core library organizational planning activities that involve people (library employees) as the focus, rather than physical structures (architecture and space).

I don’t have the skills to work as an architect and I don’t think that I should have these skills. It makes sense to bring in consultants for these kinds of tasks. On the other hand, I think it is very problematic for consultants to be brought in for things such as strategic planning or reorganization. (Corey, library worker)

Figure 1. Q3: What was the focus of consultant work in your library? (choose all that apply)

Note: There were ten predefined categories of consultant work, with an opportunity for participants to add other responses, most of which fell into one of these ten categories. Other notable areas of focus for which consultants were hired include IT projects (n=20), evidence-based decision-making (n=10), information literacy training (n=4), and outcomes assessment (n=3). Five other individual responses did not fall into any of these areas.

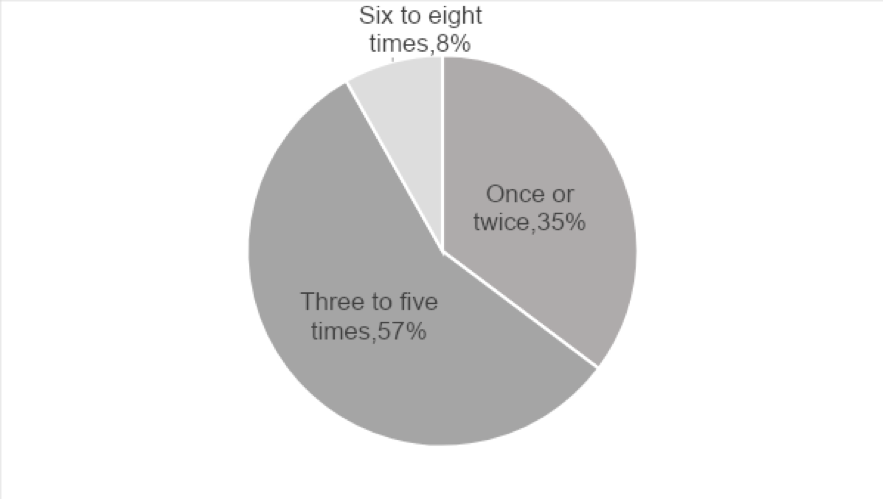

Participants could choose or list all areas of consultant work that applied to their experience, resulting in a total of 390 responses across all library employees. As depicted in Figure 2, over half of our respondents indicated that consultants had been hired three, four, or five times in their libraries, each for a different type of consulting work. These responses support our statement that the practice of hiring consultants is a trend, affecting multiple areas of work in Canadian academic libraries.

Figure 2. Q3: Number of times consultants hired in my library (number of respondents in parentheses, with 122 respondents providing 390 total responses, across both library employee groups)

Full equivalent of this figure as a list.

| Count of consultant use (122) | Once (18) | Twice (25) | Three times (27) | Four times (23) | Five times (19) | Six times (8) | Seven times (1) | Eight times (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 15 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 16 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

Impact and Value of Consultants

| Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|

| … my workplace | 29% (36) | 42% (53) | 29% (37) |

| … library services | 23% (29) | 51% (64) | 26% (33) |

| … library patrons | 11% (14) | 61% (77) | 28% (35) |

Full equivalent of this table as a list

The notion of consultant value was also investigated by asking library employees to agree, disagree, or remain neutral concerning a variety of statements (see Table 5). We found that administrators agreed with the statements that consultants are unbiased and provide specialized expertise. Although 62% of administrators thought consultants provide fresh ideas, almost 40% thought that consultants are not useful in terms of providing ideas that they have not already considered. Interestingly, only 19% of administrators believed that consultants should be hired more often, and 67% are neutral on this topic. Library workers were most agreeable about the specialized expertise provided by consultants (78%). Similar to the administrators, 64% agreed with the statement that consultants provide fresh ideas and almost 40% indicated that their ideas are not new. Library workers were less agreeable about bias, with over half in disagreement or unsure about consultant bias. Regardless of the value that consultants may bring to a library, administrators and library workers were both unsure about hiring consultants more often.

| Value of consultants | Administrators | Library workers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultants… | Agree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Disagree | Neither |

| … provide fresh ideas | 62% (13) | 24% (5) | 14% (3) | 64% (108) | 14% (23) | 22% (37) |

| … are unbiased | 76% (16) | 10% (2) | 14% (3) | 44% (73) | 27% (45) | 29% (49) |

| … provide specialized expertise | 86% (18) | 0 | 14% (3) | 78% (131) | 4% (7) | 18% (30) |

| … should be hired more often in our library | 19% (4) | 14% (3) | 67% (14) | 15% (25) | 35% (58) | 50% (84) |

Full equivalent of this table as a list

Discussion

We obtained a sample of respondents from across Canadian English language academic institutions who were candid about their experiences with consultants in their libraries, and perceptions of the practice. To further examine our findings, we break down our discussion into three sections to address our research questions that focus on motivations, impact, and perceptions of the practice. Section one discusses the motivations for hiring consultants in Canadian academic libraries. We find that consultants were hired for a variety of organizational work across many instances, supporting our argument that the practice of hiring consultants is a trend, affecting multiple areas of work in Canadian academic libraries. Section two addresses the impact of consultants on work and workplace culture in libraries. Our results indicate conflicted or hesitant views by both groups of respondents. That is, all library employees were unsure about the impact of consultants on their work and workplace, but, at the same time, were critically engaged with the conversation about it. Library workers also reported a lack of agency for themselves and their colleagues and reflected on the impact of this practice. Section three expands on the broad range of perceptions about the practice detailed by both groups. Surprisingly, participants agreed that consultants are unbiased, and provide expertise and fresh ideas. It is surprising because there is a noticeable disconnect between these positive characterizations, and the participants’ lack of desire to have consultants work more in their libraries.

I. Motivations for hiring consultants

When we review the respondents’ perceived motivations for hiring consultants in libraries, our findings are consistent with those in the literature. Hiring consultants is a trend (Harrington & Dymarz, 2018); there is marked dissonance for employees who work in a public institution under neoliberal ideologies (Seale, 2013); and there is a lack of transparency about the practice (DeLong, Sorensen & Williamson, 2015).

Consultant work in library organizational areas such as strategic planning, change management, staff reorganization, staff development and team building was reported frequently (63%, 48%, 46%, 32% and 25% respectively – see Figure 1). That is, the frequency of comments and opinions about consulting projects from both groups of respondents made it an important theme to explore further. Figure 2 shows that it is common for consultants to be hired on more than one occasion. By combining the results of Figures 1 and 2, we can assume that consultants are hired for a variety of organizational work across many occasions. These responses support our statement that the practice of hiring consultants is a trend, affecting multiple areas of work in Canadian academic libraries.

Neoliberal ideologies figure prominently in our analysis and understanding of the practice of hiring consultants and are also reflected in the voices of some of the respondents. Broadening our approach to the question of “Why do you think consultants are hired?” moves us away from operational considerations to analytical ones and provides us with a more nuanced view of the practice.

For example, some participants explicitly spoke to the neoliberal ideology underpinning the practice of hiring consultants:

It seems to me, though, that consultant work has grown out of a business model where profit motif is the leading logic. Consultants in this instance don’t bring fresh ideas; they bring capitalism. The academic library I work in and almost all libraries do not generate profit and so this ideology is counter to the very being of libraries. I would love a consultant that was an anti-capitalist library advocate. (Corey, library worker)

There is a sense that the consultant will swoop in, with an incomplete understanding of our environment, and apply standard business techniques to our situation, whether those techniques are appropriate or not. (Frances, library worker)

A number of respondents refer to policies or outcomes that evolve as a result of working in a neoliberal environment of doing more with less (Bousquet, 2008). Library workers spoke indirectly to the structures of neoliberalism by referring to “certain tasks and responsibilities being outsourced” due to lack of staff (Kelly, library worker), or to a “troubling scope creep where consultants are hired to do project work that really should be done by librarians” (Renee, library worker).

Hiring consultants to define and measure the library’s value are neoliberal rationales that may not align with the values and code of ethics of library workers. We suggest that there is a disconnect between ethical guidelines and values of librarianship when corporate models are used for organizational change including library restructuring and strategic planning. Similarly, some respondents noted the dissonance between the values inherent in libraries and in the practice of hiring consultants. Two library workers in particular speak to the values of library ethics versus the values present in the practice of hiring consultants:

I was once presented with a list of potential values generated by a consulting firm as part of our library reorganization process, and among the options listed was “winning”. It was hard for me to trust that the consultant had the library’s best interest in mind if “wining” was on offer as a value.” (Alex, library worker)

The academic library I work in and almost all libraries do not generate profit and so this ideology is counter to the very being of libraries. (Corey, library worker)

A lack of transparency was seen in the CARL study (DeLong, Sorensen & Williamson, 2015), where “only 14% of institution respondents (in our study referred to as administration) reported to have involved staff in the change decision-making process which is one of the most established methods of exacting successful change” (p. 28). Similarly, a lack of transparency was described in open-ended responses from library workers: consultants were hired because administration, management, or the “higher ups” wanted to get something done without involving library staff.

I think [our library director] was more influenced by what the higher-ups wanted than what staff actually wanted or needed.” (Micha, library worker).

II. Impact of the Practice on Work and Workplace culture

Our findings reveal a mix of perspectives about the impact of consultant use in regard to the organization and the individual. Problems with power in terms of organizational structure and lack of agency in consulting relationships highlighted in our literature review (Diefenbach & Sillince, 2011) are further unpacked in this section.

The theme of organizational hierarchy surfaced most when respondents critiqued the exercise of power by administration. Consultants were identified as a tool for administration:

Consultants are not necessarily objective. They may consciously or unconsciously provide solutions/ideas that are in line with management/administration’s desires. After all, that’s who’s paying the consultant fees. (Sam, library worker)

The following participant condemns a misuse of power in which administration avoids taking full responsibility for a decision made through the use of a consultant. This deferral of responsibility serves to problematize the dynamics of organizational hierarchy:

Use of consultants is a management technique to effect change without management having to take responsibility for the change. Most believe the outcomes are foregone conclusions, already decided on by management, [they are] using the consultant to give the illusion [of] staff participation. This makes people distrustful of management and less engaged in their workplace. (Lee, library worker)

When the consultant intervention is, in the words of another library worker “chiefly symbolic” (Jordie), then library staff can feel demoralized. This is linked to the theme of agency, specifically loss of power.

The practice of hiring consultants was also identified by some participants to be disempowering not only for themselves, but also for their co-workers. Reflecting on workplace culture in Canadian research libraries, the CARL study found that job satisfaction is not only related to what people do in their jobs, but that it is based on a variety of intrinsic indicators including relationships, equality of treatment, work life balance, and empowerment (DeLong, Sorensen & Williamson, 2015).

Some of the terms that surfaced spoke to a loss of power, as well as disillusionment, disengagement, distrust, and feeling undervalued. It is not surprising then that only 15% of library workers think consultants should be hired more frequently. Administrators also identified with a loss of influence and importance. This loss of power should not be surprising since only 19% of the administrators believe that consultants should be hired more often (see Table 5).

The practice of hiring consultants in general has made employees feel insecure, distrustful of administration, concerned for the stability of their positions, and cost a good deal of time with very little outcome. The practice of hiring consultants has in general had a negative impact on the culture of my workplace. It has contributed to low morale. (Val, library administrator)

Still other participants expressed a lack of agency, not necessarily by the fact that consultants were hired, but by the fact that the consultation process left them feeling powerless. The following quotes come from library employees with various roles within the library, but all speak to the same theme of disempowerment or decreased agency:

Staff seem to feel that we are being asked for feedback but that the ask for feedback is superficial – it’s pandering. Decisions have already been made. (Sean, library worker)

Many of the librarians commented on why we bother with consultations if they don’t listen anyway. (Taylor, library worker)

The person’s expert opinion was valued over the knowledge and experience of the people in the library. (Rory, library administration)

In other instances, the practice of hiring consultants had a positive impact on individuals. Respondents noted the ability to bring in expertise in areas not currently covered by the library, along with an increase of internal skills as a result of consultant work. It is interesting that respondents from both groups spoke to feelings of empowerment after working with consultants:

It has made our workplace more of a team-based workplace. People are more respectful of each other. (Lou, library worker)

It can be energizing and helps us to break out of entrenched patterns of thinking. (Taylor, library worker)

[It] expanded my understanding of areas in which I have worked with them; allowed the library to move forward in areas where we lacked in-house expertise. (Pat, library administration)

When reporting on the impact of hiring consultants, respondents on the whole provided a fairly balanced view. In thinking about a specific consultant intervention, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with three statements: impact on workplace, library services, and library patrons (see Table 4). The majority of responses for each impact statement assembles around the option “neither agree, nor disagree”. While a cursory analysis presents a cautious view of the practice, the volume of the qualitative data speaks to a more conflicted view: over 75% of respondents provide further clarification in open ended questions. There is a disconnect between the closed- and open-ended responses. Critical engagement with the survey topic further demonstrates that both groups of participants want to be involved in the discussion about the practice, but they are unsure, conflicted or hesitant about how they feel. As the workers whose labour may be affected, listening to their voices is necessary to understand the impact of consultants on work and workplace culture.

III. Perceptions About the Practice

In the final section we discuss general perceptions of consultants through the language used when talking about the practice. Many of these perceptions were identified in our introductory work about consultants (Harrington & Dymarz, 2018). In this research, we identified three core characteristics of library consultants: they bring expertise, are unbiased, and bring fresh ideas. These characteristics were repeated over time in LIS materials without evidence to support or dispute claims of expertise, objectivity, or fresh ideas. Respondents in the current study largely agreed with the characterization of consultants as presented in the literature either by way of agreement or critique. Library employees also repeated the assumption that consultants are hired because of “objective advice”:

My experience with hired consultants […], is the “objective advice” provided by the consultant tends to vary depending on the consultant’s expertise, knowledge, qualifications and skills. I’ve had a mix of extremely positive experiences and not so positive experiences. (Jesse, library administrator)

Others provided a more impartial evaluation:

Sometimes libraries may hire consultants when they need to make some important changes. The consultant will be perceived as a “neutral expert”. However, there may be the equivalent expertise in the library, but this expertise may not be perceived as being neutral. (Jamie, library worker)

The use of figurative and polarizing language was also identified in our earlier work and replicated in the open-ended survey responses. We previously argued that the use of figurative language obscures the real nature of consultant work and circumvents the need for a more rigorous analysis of impact and outcome. That is, figurative and indirect language become distractions in the discussion about consultants. Interestingly, these linguistic strategies were also provided by library workers:

The old expression about a consultant being someone who asks to borrow your watch, tells you what time it is and then hands you a bill, is very accurate in my opinion. (Riley, library worker)

They can serve as an honest broker and get people together but sometimes they also have their own agendas which do not fit well in a library setting. (Quinn, library worker)

Polarizing language similarly restricts the opportunity for a more nuanced understanding of the practice. By positioning the consultant as being entirely good or bad, the resulting discourse fails to support a fruitful discussion with room for both positive and negative perspectives, approaches, and outcomes with regard to consulting activities. In the qualitative data, there are numerous polarizing, critical statements from the library workers group when characterizing the practice. Consultants cause resentment and jealousy (Adrian), the practice is called dysfunctional (Elliott), and consultants are distrusted and treated with suspicion (Harper). Furthermore, the following example expresses outright contempt:

In my librarian circles, “consultant” is almost a curse word. I (and many of my colleagues) don’t respect those who are recognized as leading library consultants in Canada. They’ve got corporate models, stale opinions, and a lack of intersectional analysis. (Cassidy, library worker)

No impact on my work, except it’s an annoying distraction that provides no real purpose for the librarian and staff but allows management to appear constructive and responsive… ticks the boxes of responsible management without actually doing anything meaningful. (Jean, library worker)

Other responses depict a balanced perspective about consultants that allows room for both positive and negative aspects and a more nuanced and helpful discussion about the practice. For example, the following quote weighs the positive outcomes of consultant work with the negative emotions of colleagues.

It has led to some good outcomes, providing an outlet for some employees to share concerns about change in the workplace and address communication difficulties within work groups. In some cases, it resulted in (or reinforced) employee cynicism about proposed changes to the workplace and bitterness about resources being expended on hiring consultants. (Michel, library worker).

Whereas some respondents resisted the popular characterizations of consultants found in the literature, many reproduced these themes. One explanation could be that the lack of analytic discourse related to the practice encourages our community to uncritically adopt it. Perhaps by furthering the kind of research presented here, a critical awareness can be developed within our literature and academic librarianship.

Recommendations for future research

In hindsight, there are a couple of things we would do differently next time. Due to language restrictions of the researchers, only anglophone institutions were targeted, but future work would ensure francophone institutions were included. Future work would also include precarious employees, whether they are part-time or full-time workers. Additionally, we would keep the survey open longer, sending reminder emails to library administrators to encourage more participation. Inferential statistics were not successful due to the small number of responses. We could not substantiate any conclusions of statistical significance between the library employee groups, for example. However, the substantial number of open-ended responses and the depth of individual written responses provided rich qualitative data and allowed us to look for emerging and pre-defined themes that enriched our discussion. While our sample draws together a variety of library worker voices, we acknowledge that our survey design inherently suffers from self-selection bias.

Conclusion

Our findings represent a cross-section of Canadian English language academic library employees who were candid about their experiences with and perceptions of consultants in their libraries. The survey results give us a preliminary understanding of some of the motivations for hiring consultants as well as a way to talk about the impact of the practice. We previously identified the practice as a product of neoliberal values that has been uncritically adopted across librarianship while it grew across all library sectors seemingly unchallenged.

In summary, we find consultants are hired for a variety of organizational work across many occurrences, supporting our argument that the practice of hiring consultants is a trend, affecting multiple areas of work in Canadian academic libraries. Also, library employees are unsure about the impact of consultants on their work and workplace, but, at the same time, are critically engaged with the conversation about it. Library workers report a lack of agency for themselves and their colleagues and reflect on the impact of this practice. Loss of power, disillusionment, disengagement, and distrust are all feelings that further support our findings that most participants do not think consultants should be hired more often. In contrast, participants generally agree that consultants are unbiased, provide expertise and fresh ideas. This is surprising because we thought library workers would be less agreeable with the types of linguistic strategies used when characterizing consultants, particularly when they do not think they should be hired more often in their libraries.

We suggest that the trend of hiring consultants for organizational work, along with the unquestioned acceptance of the practice continues to replicate the descriptions and characteristics of consultants, and implicitly discourages a critical understanding of it (Harrington & Dymarz, 2018). By thinking critically about how our work, and how the work of our colleagues is shaped by normative practices, such as hiring consultants in our libraries, we can raise awareness of how we resist or perpetuate the dominant values of our time.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the survey participants for candidly sharing their experiences and perceptions about consultants in their libraries. We also acknowledge the thorough and thoughtful feedback from Karen Nicholson and Denisse Solis. Their suggestions for further reading were essential, and their kind and supportive reviews guided us to reorganize and rewrite this paper. Thanks also to Ryan Randall who helped ensure all of our figures and tables are accessible for all readers, and to Ian Beilin for editorial support and updating the timeline to fit our life priorities, beyond librarianship.

References

Adler, M. A. (2015). Broker of Information, the “Nation’s Most Important Commodity”: The Library of Congress in the Neoliberal Era. Information & Culture, 50(1), 24–50. https://doi.org/10.7560/IC50102

American Library Association. (2019). Core Values of Librarianship. Retrieved June 5, 2019, from Advocacy, Legislation & Issues website: http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/corevalues

Appelbaum, S. H., & Steed, A. J. (2011). The Client-Consulting Relationship: A Case Study of Critical Success Factors at MQ Telecommuniques. Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER), 2(2). https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v2i2.2856

Arnold, J. (2010). The community college conundrum: workforce issues in community college libraries. Library Trends, 59(1), 220–236.

Berry, J. N. (Ed.). (1969). Directory of library consultants. New York: Bowker.

Blackler, F. (2011). Power, politics, and intervention theory: Lessons from organization studies. Theory & Psychology, 21(5), 724–734.

Bousquet, M. (2008). The Corporate University. Knowledge & Power in the Global Economy: The Effects of School Reform in a Neoliberal/Neoconservative Age. New York: Routledge.

de Stricker, U. (2008). Is consulting for you?: a primer for information professionals. Chicago: American Library Association.

de Stricker, U. (2010). Part II: Consulting: Helping clients plan, adapt, choose… and much more. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 37(1), 45–46.

DeLong, K., Sorensen, M., & Williamson, V. (2015). 8Rs REDUX Carl Libraries Human Resources Study: for Canadian Association of Research Libraries (CARL). Ottawa: Canadian Association of Research Libraries.

Diefenbach, T., & Sillince, J. A. (2011). Formal and informal hierarchy in different types of organization. Organization Studies, 32(11), 1515–1537.

Eggertsson, P. (1990). Economic behavior and institutions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fincham, R., & Clark, T. (2002). Critical Consulting: New Perspectives on the Management Advice Industry. Blackwell Publishers.

Garten, E. (Ed.). (1992). Using consultants in libraries and information centers: a management handbook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Harrington, M. R., & Dymarz, A. (2018). Consultants in Academic Libraries: Challenging, Renewing, and Extending the Dialogue. Canadian Journal of Academic Librarianship, 3(0). Retrieved from https://cjal.ca/index.php/capal/article/view/28203/21153

Ingles, E. B., & 8Rs Canadian Library Human Resource Study (Eds.). (2005). The future of human resources in Canadian libraries. Edmonton, Alta.: 8Rs Canadian Library Human Resource Study.

Kakabadse, N. K., Kakabadse, A., & Louchart, E. (2006). Consultant’s role: a qualitative inquiry from the consultant’s perspective. Journal of Management Development, 25(5), 416.

Lockwood, J. D. (1977). Involving Consultants in Library Change. College & Research Libraries, 38(6), 498. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_38_06_498

Lynch, B. P. (1979). Libraries as Bureaucracies. Library Trends 27, 259–67.

Matthews, J. R. (1994). The effective use of consultants in libraries. Library Technology Reports, Nov(1), 745.

Pozzebon, M., & Pinsonneault, A. (2012). The dynamics of client–consultant relationships: exploring the interplay of power and knowledge. Journal of Information Technology, 27(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2011.32

Prytherch, R. J. (2005). Harrod’s librarians’ glossary and reference book: a directory of over 10,200 terms, organizations, projects and acronyms in the areas of information management, library science, publishing and archive management (10th ed). Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Robbins-Carter, J. (1984). Library Consultants: Client Views. Drexel Library Quarterly, 20(2), 88–99.

Scale, M. (2016). The Partner-Consultant: Partnering with Clients in Consulting. AIIP Connections, 30(3), 8–9.

Schell, H. B. (1975). Library Consultants and Consulting. Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, 15, 201–224.

Seale, M. (2013). The neoliberal library. In Shana Higgins and Lua Gregory (Eds.), Information literacy and social justice: Radical professional praxis (pp. 39–61). Retrieved from http://eprints.rclis.org/20497/

Skrzeszewski, S. (2006). The knowledge entrepreneur. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press.

Thompson, E. H., & American Library Association (Eds.). (1943). A.L.A. glossary of library terms: with a selection of terms in related fields. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Townsend, R. (1970). Up the Organization. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Wormell, I., Olesen, A. J., & Mikulás, G. (2011). Information consulting: guide to good practice. Oxford: Chandos Publishing.

Young, H., & Belanger, T. (Eds.). (1983). The ALA glossary of library and information science. Chicago: American Library Association.

Appendix A: Full Descriptions of Tables and Figures

Full Description of Table 1. Includes Question 19 and 23: Responses by Employee Group and Academic Affiliation

Table 1 represents the employee group and academic affiliation of all respondents:

- 10%, or 2 administrators from Colleges

- 90% or 19 administrators from Universities

- 11% or 18 library workers from Colleges

- 87% or 146 library workers from Universities

- 2% or 4 library workers from Canadian consortium

Total of 21 administrator respondents, which is 11% of total respondents.

Total 168 library worker respondents, which is 89% of total respondents.

Full Description of Table 2. Question 22: Responses by Geographic Location and Employee Group

Table 2 represents the employee group by geographic location in Canada. A total of 21 administrators and 158 library workers are included in this table.

- In British Columbia, there are 9 administrator respondents and 49 library workers

- In Alberta, there are no administrator respondents and 20 library workers

- In Saskatchewan, there is 1 administrator respondent and no library workers

- In Manitoba, there are no administrator respondents and 8 library workers

- In Ontario, there are 8 administrator respondents and 58 library workers

- In Québec, there is 1 administrator respondent and 7 library workers

- In New Brunswick, there is 1 administrator respondent and 1 library worker

- In Nova Scotia, , there is 1 administrator respondent and 11 library workers

- In Prince Edward Island, there are np administrator respondents and 1 library worker

- In Newfoundland and Labrador, there are no administrator respondents and 3 library workers

Full Description of Table 3. Consultants hired, and the role of library employees in the process

Table 3 represents a variety of experiences with consultants and respondents were asked to indicate yes, no or unsure. The responses are organized by the questions asked:

- Question 1: My library has hired a consultant in the past, had 189 total responses

- 13 or 62% of administrators indicated yes

- 5 or 24% of administrators indicated no

- 3 or 14% of administrators were unsure

- 108 or 64% of library workers indicated yes

- 23 or 14% of library workers indicated no

- 37 or 22% of library workers were unsure

- Question 11: I was involved in the hiring process had 120 total responses

- 5 or 38% of administrators indicated yes

- 8 or 62% of administrators indicated no

- 14 or 13% of library workers indicated yes

- 93 or 87% of library workers indicated no

- Question 12: I participated in the consultation process, had a total of 120 responses

- 10 or 80% of administrators indicated yes

- 3 or 20% of administrators indicated no

- 68 or 64% of library workers indicated yes

- 39 or 36% of library workers indicated no

- Question 30: I have worked as a consultant in the past, had a total of 186 responses

- 6 or 30% of administrators indicated yes

- 14 or 70% of administrators indicated no

- 10 or 6% of library workers indicated yes

- 156 or 94% of library workers indicated no

Figure 1. Question 3: What was the focus of consultant work in your library?

Figure 1 represents the type of work for which consultants were hired. Respondents could choose all the types of work that they experienced:

- 72% of respondents had experience with consultants and architecture / space planning

- 63% of respondents had experience with consultants and strategic planning

- 43% of respondents had experience with consultants and change management

- 46% of respondents had experience with consultants and staff reorganization

- 32% of respondents had experience with consultants and staff development

- 25% of respondents had experience with consultants and team building

| Architecture / space planning (72%) | Strategic planning (63%) | Change management (48%) | Staff reorganization (46%) | Staff development (32%) | Team building (25%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrators (number of respondents) | 11 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| Library workers (number of respondents) | 76 | 67 | 50 | 50 | 35 | 27 |

Figure 2. Question 3: Number of times consultants have been hired in my library

Figure 2 consists of a pie chart and a table. The pie chart represents the total number of times consultants were hired across employee groups:

- 35% of respondents had experience with consultants once or twice

- 57% of respondents had experience with consultants three to five times

- 8% of respondents had experience with consultants six to eight times

The table portion of Figure 2 gives a percentage count for the number of times consultants were hired across employee groups:

- 18 or 15% indicated that consultants were hired once

- 25 or 20% indicated that consultants were hired twice

- 27 or 22% indicated that consultants were hired three times

- 23 or 18% indicated that consultants were hired four times

- 19 or 16% indicated that consultants were hired five times

- 8 or 7% indicated that consultants were hired six times

- 1 or 1% indicated that consultants were hired seven times

- 1 or 1% indicated that consultants were hired eight times

Table 4. Question 14: The consultant had a positive impact on…

Table 4 depicts responses to statements about consultant impact, with closed choices of agreement. These results are across both employee groups, with a total of 126 respondents.

- For the statement, the consultant had a positive impact on my workplace:

- 36 or 29% agree

- 53 or 42% neither agree nor disagree

- 37 or 29% disagree

- For the statement, the consultant had a positive impact on library services:

- 29 or 23% agree

- 64 or 51% neither agree nor disagree

- 33 or 26% disagree

- For the statement, the consultant had a positive impact on library patrons:

- 14 or 11% agree

- 77 or 61% neither agree nor disagree

- 35 or 28% disagree

Table 5. Question 17: Perceived value of consultants

Table 5 depicts responses to statements about the value of consultants, with closed choices of agreement. These responses are broken down by employee groups.

- For the statement, consultants provide fresh ideas:

- 13 or 62% of administrators agree

- 108 or 64% of library workers agree

- 5 or 24% of administrators disagree

- 23 or 14% of library workers disagree

- 3 or 14% of administrators neither agree nor disagree

- 37 or 22% of library workers neither agree nor disagree

- For the statement, consultants are unbiased:

- 16 or 76% of administrators agree

- 73 or 44% of library workers agree

- 2 or 10% of administrators disagree

- 45 or 27% of library workers disagree

- 3 or 14% of administrators neither agree nor disagree

- 49 or 29% of library workers neither agree nor disagree

- For the statement, consultants provide specialized expertise:

- 18 or 86% of administrators agree

- 131 or 78% of library workers agree

- none of the administrators disagree

- 7 or 4% of library workers disagree

- 3 or 14% of administrators neither agree nor disagree

- 30 or 18% of library workers neither agree nor disagree

- For the statement, consultants should be hired more often in our library:

- 4 or 19% of administrators agree

- 25 or 15% of library workers agree

- 3 or 14% of administrators disagree

- 58 or 35% of library workers disagree

- 14 or 67% of administrators neither agree nor disagree

- 84 or 50% of library workers neither agree nor disagree

Appendix B: Survey Instrument—Consultants in Canadian Academic Libraries

For the purpose of this study a consultant is “an individual offering a range of professional skills and advice relevant to the operation of libraries. Usually these skills will be marketed on a commercial basis by a […] person who is not directly employed by the library concerned but retained on contract for a fee” (Prytherch, 2005, p. 350). Consultants can work individually or in teams.

1. To your knowledge, has your library ever hired a consultant?

● Yes / No / Unsure

2. What do you think are some of the reasons that a consultant has not been hired in your library? Please select all that apply.

❏ It is too expensive.

❏ It is not common practice at my institution to hire consultants.

❏ It is not common practice at my library to hire consultants.

❏ There has not been a need to hire a consultant.

❏ We rely on our internal expertise.

❏ Not sure

❏ Other ______________________

3. Think of all of the instances when consultants have been hired in your current library. Please select all areas of focus that consultants have worked on (select all that apply).

❏ Acquisitions

❏ Archives

❏ Cataloguing/ Bibliographic Services

❏ Loans

❏ Management/ Administration

❏ Reference/ Instruction

❏ Research Commons

❏ Special Collections

❏ Systems/ IT

❏ Other, please specify: __________

4. What are the most common reasons a consultant has been hired in your current library? Please select all that apply.

❏ to alleviate employee* workload

❏ to complete a project that requires skills or knowledge not currently held by library employees

❏ to define a problem

❏ to develop employees’ skills and knowledge

❏ to provide guidance for decision making

❏ to lend external credence to a course of action

❏ to obtain views free of political, functional, or other bias

❏ to signify the import of a process or decision

❏ Other, please specify ______________________

Thinking about the library where you currently work, please rate your level of agreement (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) with the following statements: (*Note, an employee in this survey refers to any person employed at the library irrespective of rank or employee group.) Scale: (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree)

5. It is common to hire consultants in the library to address internal issues such as team building and organizational change.

6. It is common to hire consultants in the library to deal with projects that require expertise not currently held by any library employees.

7. Library administration often looks for alternative ways to solve a problem before turning to a consultant for help.

8. If you would like to provide any further comments as to why consultants are hired in your current library, please provide them here.____________

Of all the times over the last 5 years that a consultant was hired in your library, pick the instance with which you are most familiar. If a consultant has not been hired over the last 5 years, select the most recent example you can think of. Please keep that experience in mind when answering the next set of questions.

9. What was the area of focus that the consultant was hired to work on? Select all that apply.

❏ Acquisitions

❏ Archives

❏ Cataloguing/ Bibliographic Services

❏ Loans

❏ Management/ Administration

❏ Reference/ Instruction

❏ Research Commons

❏ Special Collections

❏ Systems/ IT

❏ Other, please specify: __________

10. In your opinion, why was that consultant hired? Select all that apply.

❏ to alleviate employee workload

❏ to complete a project that requires skills or knowledge not currently held by library employees

❏ to define a problem

❏ to develop employees’ skills and knowledge

❏ to provide guidance for decision making

❏ to lend external credence to a course of action

❏ to obtain views free of political, functional, or other bias

❏ to signify the import of a process or decision

❏ Other, please specify ______________________

11. Were you involved in hiring the consultant? Yes / No

12. Were you an active participant in the consultation process? Yes / No

13. If you were an active participant, please describe your role in the consultation process. __________________

14. Keeping that same experience of working with a consultant in mind, please rate your level of agreement (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) with the following statements:

● My involvement in the consultation process was encouraged.

● The consultation process was transparent and clear.

● The initial objectives of the consultant were achieved.

● The consultant had a positive impact on my workplace.

● The consultant had a positive impact on my library’s services.

● The consultant had a positive impact on my library patrons.

● The consultant’s work was successful.

Now thinking more generally about the practice of hiring consultants in academic libraries, please reflect on how the practice has directly or indirectly shaped your experience in academic libraries.

15. Generally speaking, how has the practice of hiring consultants impacted the culture of your workplace? __________________

16. Generally speaking, how has the practice of hiring consultants impacted your work? __________________

17. Thinking generally about your perceptions of consultants, please rate your level of agreement (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) with the following statements:

● Consultants provide specialized expertise.

● Consultants provide objective advice.

● Consultants provide fresh ideas.

● Libraries should hire consultants more often.

18. If there is anything else that you would like to share regarding your perceptions of consultants, please leave your thoughts here. _______

19. Please indicate your current work environment.

● College / University / Other, please specify: __________________

20. Please select the category that best describes your institution.

● Primarily Undergraduate / Comprehensive / Medical-Doctoral

21. How many full-time students are enrolled at your institution?

● Less than 12,000 / between 12,000 and 24,000 / more than 24,000

22. Please select the province or territory you work in.

● Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Nunavut, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Yukon

23. Please indicate your job type.

❏ Librarian

❏ Library Assistant/ Library Technician

❏ University Librarian/ Chief Librarian/ Dean of Libraries

❏ Associate University Librarian/ Associate Dean of Libraries

❏ Department Head/ Division Head

❏ Other, please specify ______________________

24. Please indicate the area of the library where you currently work. Select all that apply.

❏ Acquisitions

❏ Archives

❏ Cataloguing/ Bibliographic Services

❏ Loans

❏ Management/ Administration

❏ Reference/ Instruction

❏ Research Commons

❏ Special Collections

❏ Systems/ IT

❏ Other, please specify: __________

25. Is your work governed by a collective agreement?

● Yes / No

26. How many years have you worked in an academic library?

● 0-5 / 6-10 / 11-15 / 16-20 / 21 or more

27. What age group do you fall into?

● 30 and under / 31-40 / 41-50 / 51-60 / 61 and over

28. Please select your highest level of education.

❏ Undergraduate

❏ MLS (or equivalent)

❏ Master’s (other than an MLS)

❏ MLS and another Master’s

❏ Doctorate

❏ Other, please specific: _________

29. Job satisfaction. (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree)

● Overall, how satisfied are you with your job?

● Overall, how satisfied are you with your workplace?

30. Have you ever worked as a library consultant? Yes / No

31. If yes, in what capacity? ____________________

Pingback : Consultants in Canadian Academic Libraries: Adding New Voices to the Story – FerNews.net